Edited and with an Introduction byProf. Henry W. Ehrmann (Government).New York: Frederick A. Praeger, Inc.,1965. 210 pp. $6.50.

This is a collection of papers presented to a German audience in May 1962 at the opening, at the Free University of Berlin, of the Otto-Suhr Institute, the successor of the distinguished Hochschule fur Politik. The authors, all distinguished political scientists, were Professor Ehrmann and the late Sigmund Neumann from the United States; Karl Dietrich Bracher, Richard Lowenthal, and Boris Meissner from The Federal Republic of Germany; Maurice Duverger from France; Hans Huber from Switzerland; and R. T. McKenzie from Britain. These gentlemen were invited to address themselves to a common theme:

The transformation of modern democracy and the various dangers which it has to meet should be discussed in the light of the experience of the last decades. The increase in power of the executive, the dynamic growth of the administrative machinery, the weakening of parliamentary controls by international organizations and international agreements, the crisis of the party system and its consequences for political decisions and for public opinion, the vanishing of party differences - all these factors have brought about changes in the political structure. In different countries such changes have taken different forms and have varied in intensity. For that reason we want to discuss the major governments of the West: but we also wish to draw the contrasting picture of the Soviet Union and the developing nations.

The concerns expressed in this invitation may be more Germanic than American, British, French, or Swiss, as the essays by citizens of the latter four countries suggest. The wording of the invitation and the chapter by Karl Dietrich Bracher (translated by Prof. Richard W. Sterling of Dartmouth's Department of Government) suggest that German political scientists are concerned about issues that their contemporaries in the other countries are not.

The reader may wonder if Bracher's disappointment at what he considers to be the failures of the Bonn parliament to govern springs from a belief in a form of parliamentary democracy that never has existed anywhere. He laments the development of a strong executive without, apparently, recognizing that it is possible to have such an executive and still have a strong legislature, i.e. the two have to learn to work together. R. T. McKenzie shows clearly that the British parliamentary system has existed as long as it has because it has included a strong executive - i.e. the cabinet. Duverger points out that the French parliament has never been a governing instrument, but rather, that the function of the deputy was "to be a representative of the citizen against the authority of the state."

Ehrmann is less concerned with the decline of the power of Congress than with the "individualization and decentralization of decision-making."

Lowenthal's chapter on government in developing countries presents the interesting thesis that "the large majority of genuine regimes of development has so far shown a preference for forms of government that lie between the extremes of pluralistic democracy under the rule of law and the totalitarian ideological dictatorship of the Communists," This, after he has said that, "Soviet Communism has proved itself as a gigantic engine of development," and that the "nationalistic intelligentsia of all the developing countries is fascinated by the Soviet model"!

Purchasers of this volume will not find easy reading, but if they are interested in serious analysis of the contemporary political world, this is their book.

Dean of Summer Programs

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureGraduate Study—Past and Present

November 1965 By PROF. LEONARD M. RIESER '44, -

Feature

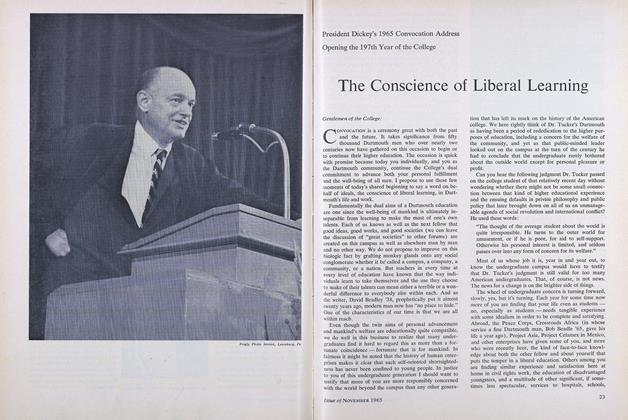

FeatureThe Conscience of Liberal Learning

November 1965 -

Feature

FeatureAn Exciting 20-Year Forward March

November 1965 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's First Lady

November 1965 By MARGARET BECK McCALLUM -

Feature

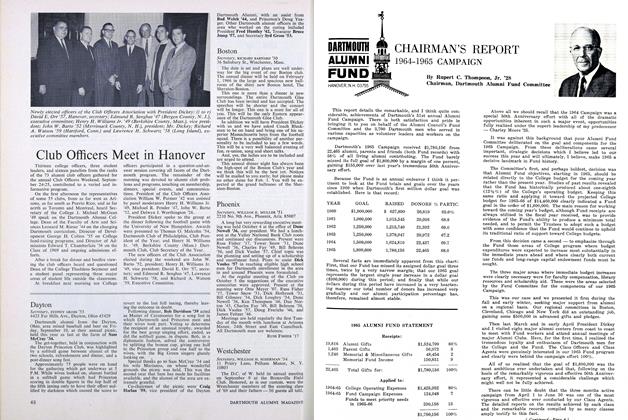

FeatureCHAIRMAN'S REPORT 1964-1965 CAMPAIGN

November 1965 By Rupert C. Thompson, Jr. '28 -

Feature

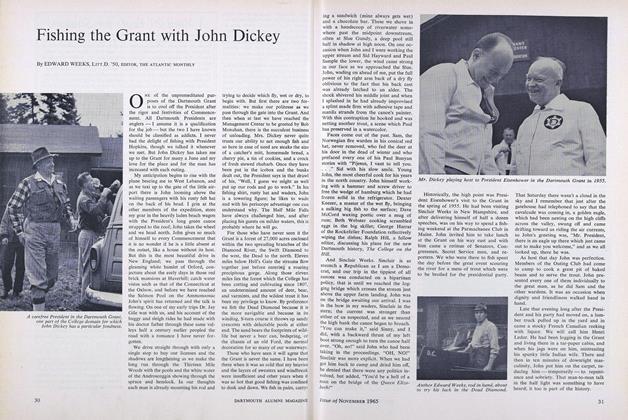

FeatureFishing the Grant with John Dickey

November 1965 By EDWARD WEEKS, LITT.D. '50,

WALDO CHAMBERLIN

Books

-

Books

BooksShelflife

Mar/Apr 2013 -

Books

Books1600 PENNSYLVANIA AVENUE.

July 1960 By FRANK SMALLWOOD '51 -

Books

BooksEND OF ROAMING

November, 1930 By Herbert F. West -

Books

BooksGENERAL EDUCATION IN THE PROGRESSIVE COLLEGE,

November 1943 By Irving E. Bender. -

Books

BooksFurther Mention

JUNE 1971 By JOHN HURD 21 -

Books

BooksTHE GREAT DESIGN: TWO LECTURES ON THE SMITHSON BEQUEST

FEBRUARY 1966 By RODERICK NASH