TWENTY-SIX years ago the Experimental Theatre was born in Hanover with the avowed purpose of presenting original plays written by Dartmouth students. Scripts by non-students would be acceptable but the aim was to confine the productions to the college writers. The birth of the organization grew out of the needs of the new playwriting course, inaugurated by Professor E. Bradlee Watson '02 within the English Department, to show student playwrights how plays looked when produced. As publication is to the student writer so a production is to the student playwright.

From the beginning Dartmouth has always been enthusiastic about one or another form of the drama. 18th century commencements featured "dramatic dialogues" wherein two students assumed the roles of great statesmen or philosophers of the past and enacted a possible (or impossible) conversation. In the 1780s a student-written play had been presented in Hanover and was taken on tour (by insistent popular demand) to Windsor, Vermont, by oxcart. Down through the 19th century plays and "dramatic representations" were recorded with more frequency than one usually assumes the Victorians encouraged. Plays in English alternated with productions of classical dramas (which invariably meant plays by the Greek and Latin authors and did not include Shakespere). The latter were always presented in "the original tongue." Out of this welter of hit-or-miss presentations grew the Dartmouth Dramatic Association some time prior to the 20th century.

There is no record that any of the plays presented by this new organization of Dartmouth drima had any connection, even remotely, with the curriculum. On the other hand, all indications point to the fact that the Dartmouth Dramatic Association and its productions were suffered for their entertainment value, or as our friends in the Armed Services would say, for morale. One college indeed did so state about this time that the dramatic club was set up "to divert the minds of the students during the term." It is reasonable to assume that the isolated location of the College at this time made this diversion a real need, and it may account for the dramatic bent of the College throughout its entire history.

Looking over the list of plays of the Dartmouth Dramatic Association it is fairly evident that the tried and true and, later, the Broadway success were appropriated and re-done for the Dartmouth audience. The record is very clear that all of these met with great favor. While this more popular fare was rising, the old and more academic production of the classics in the "original tongues" was slowly dwindling. The last bright gleam, the 1910 production of Oedipus Rex in Webster Hall ended it. It had been a legacy from the more classical period of 19th century discipline when Greek and Latin were required of everyone. Anyone with acting ability took Greek and Latin as a matter of course and could find an outlet for his talents here as well as in a modern play, and most of the audience could make a stab at understanding. With the decline of the classic discipline, casting became a problem and students, regardless of whether or not they had talent, were dragooned into acting major roles. Finally, after 1910, Dartmouth bowed to the inevitable. The Dartmouth Dramatic Association became the major outlet for "theatricals" in Hanover and rose to this challenge.

The years 1914-20 are memorable, halcyon years for the drama in Hanover. More Dartmouth students of that era seem to have entered the professional theatre and succeeded than in any period before or since. It was during that time that a play currently running in New York was produced in Hanover by the Dramatic Association. Apparently word of the success in Hanover reached the ears of the New York producer for he invited the all-male cast from Hanover to perform the play on the stage of the New York home of the hit at a matinee attended by the original professional cast and an audience of standees. This was a definite indication that the dramatic club was coming of age.

In the early 1920s the Dartmouth Dramatic Association changed its name to "The Dartmouth Players" and promptly hired a full-time director who was appointed to the college staff. Hitherto interested faculty members had acted as adisers. This marked another step along the road to maturity.

By 1924 the Dartmouth Players took their greatest step forward and welcomed women, real women, into the casts of their productions. From this vantage point it is hard to conceive what a radical step that was at the time. Many other colleges waited much longer. Perhaps it was the fact that Dartmouth depended on these plays and saw the light earlier. Or perhaps it was just that Dartmouth recognized the emancipated woman earlier. In any event, some very sensible person or persons realized that however accurate the impersonation, many serious plays cannot be done when boys play the female parts. This move signalized the fact that The Players were bursting out of the "for morale" business and that drama in Hanover was to be produced seriously from every standpoint.

From 1925 through 1928 the Dartmouth Players had four directors, one each year. The effect on the organization was far from stabilizing and in the midst of this uneasy period for The Players the Experimental Theatre was born.

THE first few productions of the Experimental Theatre were student works put on by students, faculty and members of the community. The organization was, in fact, community wide with town and gown handling props, scenery, lighting, general production and even the business side, including ushering and publicity. It was a brand new organization wholly separate from the Dartmouth Players.

The Experimental Theatre, under Professor Watson, was different in other ways too. Following the lead of Professor George P. Baker of Yale, he formed an "invited audience" who would attend these presentations free of charge and act more or less as a try-out audience. He further asked each member of the audience to submit a written critique of the play or plays after he had seen them. (This is still adhered to in the presentation of student plays today.) Many of the audience felt that they were not qualified as "critics" but it was impressed on them that the importance of the critiques was primarily the lay reaction and normal audience opinion. The success of this project was heartening and the Experimental Theatre ran through two years of its existence.

In 1928 Warner Bentley came to Hanover as Director of the Dartmouth Players. It was this appointment that was to stabilize The Players and weld the two dramatic organizations into cooperating rather than competing activities. About this time also the faculty and community elements within the Experimental Theatre began to diminish. To fill this gap the new play production course, inaugurated by Mr. Bentley, was able quite logically to take over the production of these plays as a practical laboratory. Actually the separation of the two organizations, was an illogical contradiction. Any student interested in the theatre normally belonged to both and overlooked the distinctions between them.

Despite this, the legal fiction of separation was continued for some five years longer. One amusing incident will illustrate this point. The Dartmouth Players owned a series of Kleigl 1000-watt spots as lighting equipment. The Experimental Theatre owned a comparable number of Pevear baby spotlights. Each organization needed both types of spotlights for a play. So The Players rented the baby spots for their shows, while the Experimental Theatre rented the Kleigls for their productions. As both organizations were under the Council on Student Organizations, the bookkeeper solemnly made the credit and debit entries on the books without any actual cash changing hands.

The awkwardness of this situation was resolved finally in a curiously simple manner. The Dartmouth Players had inherited from the older Dramatic Association a program of rigid performance dates which dictated performances for each of the three houseparties during the college year. The gala atmosphere of houseparties is hardly the time or occasion to present the deep, the classic or the esoteric in drama. It is true that The Players had given in-between" plays which fulfilled these specifications to a certain degree but these were spasmodic rather than regular. And here was the Experimental Theatre ready to hand, already definitely linked to the English Department and through that to the curriculum, able to round out the dramatic program of the College. Furthermore, the Experimental Theatre, subsidized by the College and committed to the presentation of student plays, could broaden its program to take over the more serious plays irrespective of their popularity. And so, around the middle 1930s the Experimental Theatre became that portion of the Dartmouth Players which was more closely integrated to the academic in the college drama and particularly to the drama courses in all departments.

A special director for the Experimental Theatre was appointed and the program was put into effect. The original program for both The Players and the Experimental Theatre comprised ten presentations a year, evenly divided between the two organizations. Plays, or scenes from plays if the production seemed otherwise unwieldy, from Shakespere or modern experimental plays. The first year this program was literally given away. There were no tickets and no critiques were demanded. It was come one, come all, and it was an obvious failure from the start. The audience of less than 100 who gathered for the original presentation dwindled to about twenty by the third play some months later. It was obvious that no one values anything he doesn't have to pay or work for.

The following year this system was corrected. A very "select list" was prepared and "invitations" were sent out asking that those so selected become members of the Experimental Theatre audience to see and criticize the performance of WingsOver Europe. The return of a written critique was mandatory for the member's retention on the invited list. Curiosity, and possibly snobbishness, overcame lassitude. The second play, Moliere's LesPrescieuse Ridicules (in English), was presented for two nights (an unusually long run at that time) and the response was so excellent that the third play was presented for three performances. Here the number has usually remained and the faithful of the audience wrote their critiques from then on until the production of Jim.Dandy late in November 1942. This was the last presentation of the Experimental Theatre for the duration of the War. It resumed in November 1947.

The mandatory criticisms were not just a "come-on." They were extremely helpful as a guide to both faculty and student workers in all phases of each production. They represented, at once, individual and mass opinion. In more than one instance they refuted and reversed the decision of the critic of The Dartmouth which is normally the only voice one hears. Further than this lay the hope that the members of the audience would themselves come to feel that they were part of a creative scheme of production. Often, however, many members forgot that the word criticism meant evaluation rather than derogation. This type of criticism usually contained a list of all the adverse elements and ended surprisingly by summing the play up as one of the most enjoyable they had ever seen. By and large, however, all criticisms were valuable and their contents were read and re-read by all who were intimately connected with the current production.

IN 1947 the Experimental Theatre was revived with the production of Moliere's Tartuffe. The 17th century classic was followed by a bill of three one-act plays covered by the title "Plays from Three Centuries." These included Richard B. Sheridan's St. Patrick's Day, Maddison Morton's Sent to the Tower, and Russell Graves' U 235 and K2. The last play had been written in Hanover one month before the presentation. The purpose of this bill was to show the audience the varying styles of production of the centuries bridged by the plays - also to bring clearly to the audience's mind the character of Experimental Theatre presentations after a five-year hiatus. These plays were again presented free of charge and a new list was drawn up for three complete audiences; criticisms were again made mandatory and this system was continued until about three years ago. It was finally discontinued when the growth of the audience imposed a burden on the office staff far in excess of any other organization's demands and threatened to overwhelm the Council on Student Organizations.

Furthermore, the newer productions were rather more sumptuously mounted and this, combined with the general rise in prices of everything, made these postwar plays about four or five times more costly than any of the prewar productions. King Lear, for example, was originally intended for a regular free-of-charge Experimental production but became so costly that it would have eaten up the entire year's budget. It was presented as a play by the Dartmouth Players and the Experimental Theatre and more than paid back its cost. In this case no critiques were demanded and none was submitted.

It was, indeed, the production of KingLear that established the fact that these serious, classic and esoteric plays could stand on their own feet as "box-office draws." What had begun in the middle 1930s as an attempt to round out the season with serious plays and somehow lure an audience to see them was now something quite different. The Experimental Theatre had "come of age." It was now no chore to attract a Hanover audience to the plays of Shakespere or Aeschylus. Most of the community were heartily willing to pay to see the arena experiment of Moliere's The Doctor in Spite of Himself set in the center of Robinson Hall with the audience sitting all around the central acting area and on the stage itself.

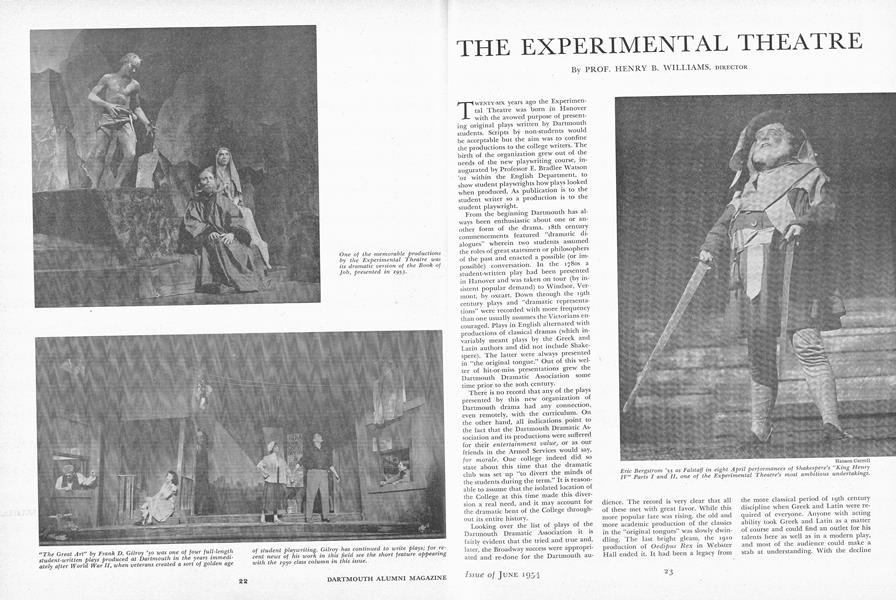

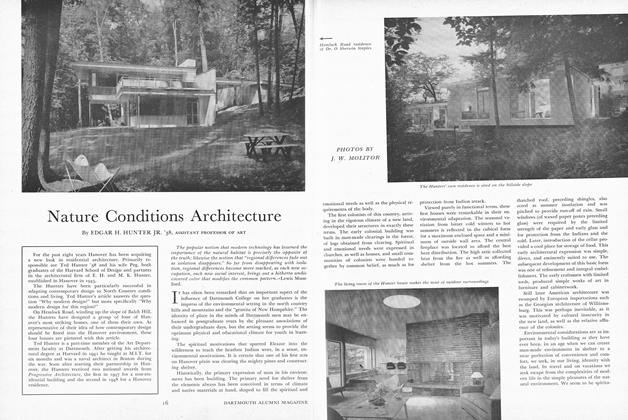

In 1953 the Experimental Theatre produced The Book of Job from the Bible. It seemed evident to many for the first time that this classic example of patience was, in the light of this production, far from patient with his stupid sympathizers and was able to learn it only from the Lord himself speaking out of the whirlwind. This past year the Experimental Theatre dates were given over to a Shakesperean project, the production in January and April of both parts of King Henrythe Fourth. This itself was envisioned as a part of a larger plan to present next year King Richard the Second and King Henrythe Fifth. The scope of these productions crowded out two other Experimental dates, including the yearly bill of original one-act, student-written plays. The latter have been deferred until the autumn.

The Experimental Theatre has changed greatly since its inception in 1926, but the firm basis on which it was founded and the spirit that pervaded the organization at that time have always been retained. The hard core of that idea was the production of student scripts. Obtaining these will be harder since the reduction of the playwriting course to a single semester, but the indications are that they will come nonetheless. A play is one of the most difficult of all literary forms and, generally speaking, most students of college age cannot be expected to handle successfully more than the one-act play. Immediately following the war maturer veterans for four years turned out four successful full-length plays, all of them produced by the Dartmouth Players or the Experimental Theatre; at least two of these student authors have succeeded further in writing for the theatre and television. With the passing of the veteran student we have returned to the one-act play, and some of the more recent productions have demonstrated developing ability among the younger students.

Some years ago, at a drama conference, I was asked to explain the Experimental Theatre to a group assembled from other New England colleges. When I had finished one gentleman from another college said: "I wouldn't call that an Experimental Theatre; I'd call that a Free Theatre." While granting this I reminded him that even freedom in college drama is experimentation. We experiment with plays, with actors, with scenery, and with the audience. It may not sound exactly like the experimental theatres of the 19205, nor even like our own Experimental Theatre of that time; yet I think the name is apt, descriptive and exact . . .and . . .as with all good experiments, we hope devoutly, some day, for a perfect production to emerge which will be so good that even the audience will consider it NON-experimental.

Hanson Carroll Eric Bergstrom '55 as Falstaff in eight April performances of Shakespere's "King Henry IV" Parts I and II, one of the Experimental Theatres most ambitious undertakings.

Henry B. Williams, Professor of English and Director of the Experimental Theatre

As an experiment this Moliere play was presented arena style in the Little Theatre

Hanson Carroll Two of the leading actors in the "King Henrythe Fourth" series this spring were JohnVarnurn '54 ..(top) as Justice Shallow, shownwith Richard Hlavac '56 as Bardolph, and(below) Robert Morton '55 as Prince Hal.

Hanson Carroll Two of the leading actors in the "King Henrythe Fourth" series this spring were JohnVarnurn '54 ..(top) as Justice Shallow, shownwith Richard Hlavac '56 as Bardolph, and(below) Robert Morton '55 as Prince Hal.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureNature Conditions Architecture

June 1954 By EDGAR H. HUNTER JR. '38, -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

June 1954 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

June 1954 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, ANDREW J. O'CONNOR, Richard Eberhart '26 -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty

June 1954 By HAROLD L. BOND '42 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1905

June 1954 By GEORGE W. PUTNAM, FLETCHER A. HATCH -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

June 1954 By G. DOUGLAS MORRIS, WILLIAM B. MINEHAN

HENRY B. WILLIAMS

-

Books

BooksSCENERY FOR THE THEATRE

January 1939 By Henry B. Williams -

Books

BooksTHE STAGE MANAGER'S HANDBOOK.

January 1954 By HENRY B. WILLIAMS -

Books

BooksWATERFRONT.

January 1956 By HENRY B. WILLIAMS -

Books

BooksTHEATRES AND AUDITORIUMS

JUNE 1965 By HENRY B. WILLIAMS -

Books

BooksPRIVATE.

DECEMBER 1970 By HENRY B. WILLIAMS -

Books

BooksTHE TRINIDAD CARNIVAL, MANDATE FOR A NATIONAL THEATRE.

APRIL 1972 By HENRY B. WILLIAMS

Features

-

Feature

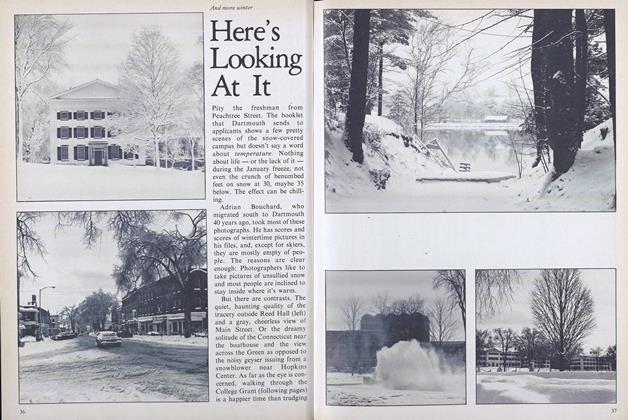

FeatureHere's Looking At It

JAN./FEB. 1978 -

Cover Story

Cover StorySIGNED ANIMAL HOUSE SCREENPLAY

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

FeatureCONJUNCTIONS, CONFLICTS & CHALLENGES

SEPTEMBER 1985 By Charles W. Moore -

Feature

FeatureMaking Ambitious Ends Meet

APRIL 1988 By Deborah Solomon -

Cover Story

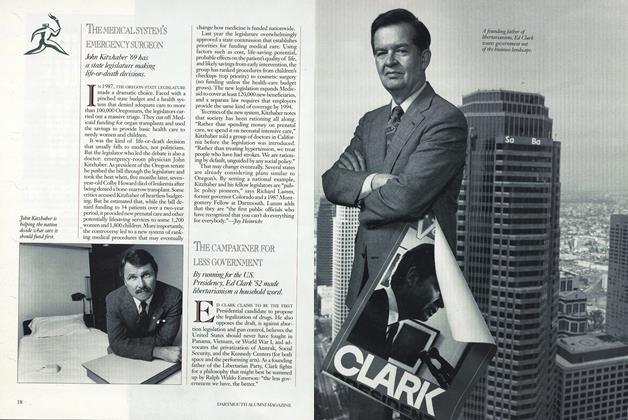

Cover StoryTHE MEDICAL SYSTEM’S EMERGENCY SURGEON

JUNE 1990 By Jay Heinrichs -

Cover Story

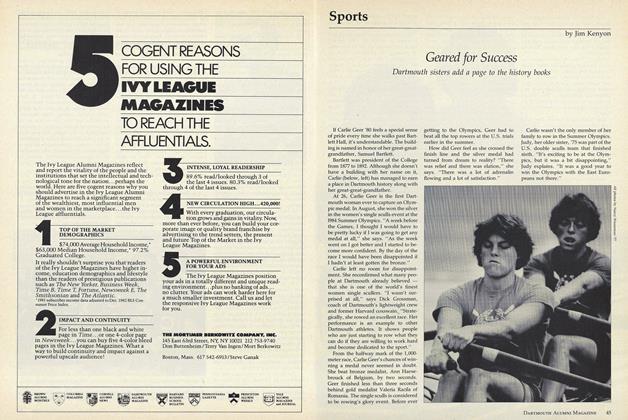

Cover StoryGeared for Success

OCTOBER 1984 By Jim Kenyon