Is This Any Way To March?

Yes, if you’re part of the Dartmouth band, which for decades has been stepping to the beat of an unabashedly irreverent tradition.

Nov/Dec 2008 Kristen LaineYes, if you’re part of the Dartmouth band, which for decades has been stepping to the beat of an unabashedly irreverent tradition.

Nov/Dec 2008 Kristen LaineYes, if you're part of the Dartmouth band, which for decades has been stepping to the beat of an unabashedly irreverent tradition.

DARTMOUTH FOOTBALL, WITH ITS 17 Ivy League titles, is the tradition that draws people through the brick arches of Memorial Stadium on fall Saturdays. The fans come, they form blocks of green and white in the alumni sections, and some of them chant "wahhoo-wah." On one cool and breezy day last November these devotees of Big Green football prepared to cheer the 2-5 home team in a matchup with Cornell. But another tradition was gathered in the end zone—the Dartmouth College Marching Band, once an integral part of the Colleges football experience. In the past half-century, as Dartmouth football has faded from national prominence, the Dartmouth band has formed a sort of counter tradition. Some might call it a traitorous one.

The ragtag ensemble that showed up for the Cornell game was certainly marching to the beat of a different drummer. Its members dressed in rumpled green blazers, dingy white pants that could have been pulled from the bottom of a laundry pile, and hats in the shapes of a Chinese pagoda, the Statue of Liberty and a skunk.

Band member Patrice Coleman '11 read from a script in the press booth: "And now, the only band in the Ivy League who thinks it's a real boy—the Dartmouth College Marionette Band." Only a few would catch the play on the band s initials. The band formed what Coleman called "a beautiful floral centerpiece" and played the 1960s classic, "Gimme Some Lovin'"—although what appeared on the field resembled little more than drooping students. Tepid applause followed a not entirely tuneful rendition of the national anthem. The band filed into four rows of seats in Section 8, the student section. As the game began the band comprised the most visible block of students in that wind-swept concrete steppe.

The Dartmouth band is nothing like a Big 10 marching band or even many high school bands. The troupe in Dartmouth green doesn't march, and its music-making skills are only slightly better than those of a bunch of middle-schoolers. It is, however, part of a pedigreed Division I breed known as the scramble band. At Dartmouth, as in the 10 or so other places where the scramble band thrives, the Marching Band has evolved (or devolved, depending on your viewpoint) through the years from a militaristic ensemble into music-making jesters seemingly spawned by Animal House.

Although the Marching Band at Dartmouth eventually came to be linked with football, it is actually a war-baby. In the decade following the Civil War, brass-band fever swept the country, spread by veterans who had learned to play in regimental bands. Marching bands quickly grew away from their military roots. By adding woodwinds to the horns and having his bands promenade while playing popular music, bandmaster Patrick Gilmore was recognized as "the father of the American band by music historians and the march king himself, John Philip Sousa. In 1887, one year after Gilmore led musical celebrations for the dedication of the Statue of Liberty, "the Dartmouth College Band" made its first promenade appearance in Hanover. (Even at the onset, the bands later obsessions could be discerned: An advertising poster offered "Fun! Fun!" and "Plenty of Young Ladies")

It took another war for the Marching Band to become a per- manent presence on campus. Shortly after news reached Hanover in the winter of 1898 that the battleship USS Maine had been blown up in Havana Harbor, a group of students led by Raymond Pearl, class of 1899, started "to toot into battered old horns" in their fraternity rooms, according to an account published in the 1899 Aegis. On May 2,1898, some 25 musicians wearing white duck trousers and yachting caps pinned with strips of white cloth led 14 volunteers for the Spanish-American War from campus to the train station. Half a century later E.B. Wardle, class of 1899 recapped the scene for his Class Notes:

"Perfect silence pervaded every line of the column—a silence so intense that the occasional order from the marshal re-echoed from the hills. Then came the sound of music, and from Dartmouth Hall issued the band, their bright instruments gleaming, their white trousers keeping time picturesquely....The band took first position; behind them the college by classes; and last of all the volunteers As the wah-hoo-wahs followed it time and again, the train passed out of sight, carrying with it the Dartmouth spirit to the war."

Within a decade that Dartmouth spirit became institutional- ized on a different field of combat, the gridiron. Sousa, Gilmores musical heir, brought his band to Hanover to perform in 1910 and 1912. The effect on the Dartmouth Marching Band was immedi- ate. "The Stars and Stripes Forever" and other Sousa marches rallied the football team at home and, starting in the 19205, at away games as well. In 1925, at the start of a season in which Dartmouth would win a national football championship, a front-page article in The Dartmouth trumpeted that the largest band in the history of the College—s6 musicians—would perform under the direction of professor M.F. Longhurst, playing at "all principal athletic contests" and Commencement exercises.

By the tim eDAM readers enjoyed Wardles 1951 recollection of the band it might have seemed the traditions of Dartmouth spir- it—the Marching Band, class cheers, school songs, Friday night pep rallies, bonfires and, of course, football—had always been and would always be around. The band was sometimes featured on the cover of football programs. The 100 musicians who filled the straight ranks and files on the field had auditioned for their spots and practiced their precise turns in three afternoon sessions each week, earning phys-ed credit as they did so.

On the day of the first home game of the 1949 season an edi- torial in The Dartmouth effused about Dartmouths tiaditions of spirit and community, a list that started and ended with the band. "Those things mean something," the editorial concluded. The Marching Band's performance in front of nearly 11,000 people at the Holy Cross game later that day, in which it played a double run-through of "Dartmouths In Town Again" (as it formed the letters for wah-hoo-wah on the field) along with several Sousa selectiond, mirrored the editorial's self-conscious sense of tradition and spirit.

But what those things meant was already changing. By the 1950s Dartmouth was no longer contending for national football championships. By choosing high academic and recruiting standards over athletic records, the schools of the newly created Ivy League all but ensured that they would be competing against only themselves.

Part of the change came with a new director, Don Wendlandt, who had marched at the University of Wisconsin and directed a military band during World War II and would, during 30 years in Hanover, earn a full professorship in the music department. Wendlandt cranked up the band's marching speed from 40 steps per minute to 175. Band members marched at a frenetic three steps per second. The musicians retained their military postures and the spit-and-polish organization, but with the faster pace came a change Wendlandt couldn't control: student innovation.

For the 1954 game against Cornell, Wilton Sogg '56, who had played clarinet in his high school band in Ohio, decided that the Dartmouth band's best chance of excelling lay in humor. So he wrote a show about fads that presented a seemingly innocuous series of band formations: bicycles, an airplane, a pair of Bermuda shorts. As the band played "Collegiate," two trombones, flanked by bass drums, marked the crotch of the Bermudas. As the song reached its fast and furious conclusion, the trombone players lifted their slides up. And up. This was not the first reference to sex in a Dartmouth show, but the slyness of the innuendo, the way the visual on the field was used as a trigger and the way Wendlandt, as a representative of adult authority, completely missed the combination until he saw the show? These were signature elements of what would become the scramble band.

Halftime performances into the 1960s featured formations shaped like cocktail glasses, beer steins and pouring kegs, party hats and aspirin tablets. Dartmouth's homegrown drinking song "Son of a Gun for Beer," became a band standard. The letters S-E-X, allegedly referring to a favorite fraternity, appeared on the field in 1963. The scripts read over the public address system urged the dates of Dartmouth men to "run, girls, run." and, in a recurring trope, led them to the Lone Pine to fulfill "a Dartmouth tradi- tion." Snippets and musical catch phrases replaced full songs, and the humor turned into satire. When the band performed for the Brown game in October 1964 the halftime show was built entirely around the upcoming presidential election. The script, once it introduced the band, didn't mention either of the teams, football or the College. When the band played "The Stars and Stripes Forever" it was in ironic counterpoint to the formation on the fieldlevers on a voting machine. The former symbol of school spirit had morphed into a mirror of campus life and campus concerns. The band was now operating in a tradition of its own, separate from the football team.

Scriptwriters, who were mostly sophomores and called "show chairs," used their public forum to explore what college sophomores care about: dining-hall food, sex, drinking. Some shows touched on larger issues, as in a 1975 performance that spoofed student and alumni reaction to coeducation. By then the College had instituted a review process. Before one game a censor in the athletic department sent a proposed "salute to bad taste" back for a complete rewrite. (To "salute" the Spanish Inquisition the band had wanted to form a Star of David and play "Onward Christian Soldiers.") The vetting didn't make much difference. As the decade progressed the scripts became raunchier—and the humor even more sophomoric.

Moreover, the band director no longer controlled the formations. "Amorphous blobs" and a marching snowball became the shapes of choice on the field. Band members now ran wildly between any on-field formations. Gone was any pretense of spit-and-polish precision.

Starting in the late 1960s and continuing into the 1980s TheDartmouth ran letters and editorials complaining about the band. The president and the athletic department received complaints from home and visiting fans alike. For people who had valued the band as an adjunct to the football team or remembered it as the soundtrack to their student days, what they saw on the field at half-time looked not like a new tradition but a betrayal of an old one.

TODAY THE BAND —and complaints about the band—are both diminished. Only about half the rosters 40 students, mostly freshmen and sophomores there to fulfill the P.E. requirement, showed up for the 2007 Cornell game. Few people stayed in the stands for the halftime show.

Band director Max Culpepper, hired as a non-faculty member in 1984 after Wendlandt retired, doesn't consider it a sign of health that the same number of students marched in the band in 2007 as when it started more than a century ago. Culpepper sees many factors at work. The D-Plan makes it difficult for him to plan the band's instrumentation from term to term and hard for students to develop as leaders. Academics now limit rehearsal time to one afternoon a week and the morning before games. Instruments are old and in disrepair. Storage, shared with several other ensembles, is under a loading dock at the Hopkins Center; Culpepper, who also directs the Dartmouth Wind Symphony, imagines prospective students looking around campus and noticing the high value placed on academics and a wide variety of sports. "It's easy to get the impression that music is not important here," he says.

"Although all the Hop ensemble budgets would benefit from increases to keep up with inflation, our Marching Band budget sufficiently funds the group for the fall season each year," says Joshua Price Kol '93, director of student performance programs at the Hopkins Center. While the Hop won't make public its budget, Kol describes the bands funding as large enough to "cover all its expenses, including two or three trips to away games, as well as a band directors assistant to accompany the band."

The bands status may have more to do with changing times than money. Perhaps playing music, whether on a marching field or in a concert hall, is not as important in America as it used to be.

"When I was a student everybody seemed to play an instrument," says Dick Jaeger '59, former director of admissions and athletic director at Dartmouth before retiring in 1989. Students arrived in Hanover having done "a little sports, a little acting and Mom said take piano" or trumpet. Decades of cuts in public school music programs across the country, however, mean fewer high school students playing instruments. Jaeger identifies another trend closer to home: Fifty years ago "the generalist ended up in the college marching band." Now Dartmouth, along with its highly selective peers, seems to specialize in specialists.

Culpepper's retirement at the end of the current academic year will open a new chapter in what Nickolas Barber '10 who co wrote the script for last November's Cornell game, calls the band's "tragedy of the commons." With the band having long existed in an administrative netherworld between student organizations, the Hopkins Center, the music department and the athletic department, band members wonder, as Barber puts it, Whose problem are we?" After decades of absorbing criticism about its marching band the College might be forgiven for not hustling to answer that question or to find it a new champion.

But Jeff James, director of the Hopkins Center since 2005, who remembers his time in the Hamilton College choir as a "deeply transformative experience," will play a key role in shaping an expected expansion of arts programs and facilities at Dartmouth. He recognizes "striking needs in music at Dartmouth and sees the importance of "telling the story" of the role that the arts play in a liberal education.

Barber has noticed that few of his non-band classmates know the music and lyrics for the old Dartmouth tunes, but band members know them all: "Dartmouth's In Town Again, Come Stand Up Men," "As the Backs Go Tearing By" and "Glory to Dartmouth."

"We're the guardians of a lot of music that otherwise would have gone by the wayside," he says. "They're wonderful songs, part of a tradition that I'm proud to be a part of, a reflection of the institution and its history."

There's irony in a student organization seen by some as an instrument of the decline in Dartmouth spirit identifying itself as a steward of that spirit. But Barber's pride points the way to a possible future for the band. What if the Marching Band also played for women's lacrosse and men's rugby games, for example, or celebrated club sport national champions in figure skating and sailing? What if band members taught Dartmouth tunes to freshmen, as the Outing Club teaches the "Salty Dog Rag?"

At the beginning of each academic year the Hopkins Center hosts a bazaar for the arts organizations on campus. The Marching Band plays "Louie, Louie" in front of the Hop, then marches down the building's hallways, through Spaulding Auditorium and back out onto the plaza. Hop director James chooses to put the group front and center for a reason that resonates through the decades: The band brings people together and reminds them to have fun.

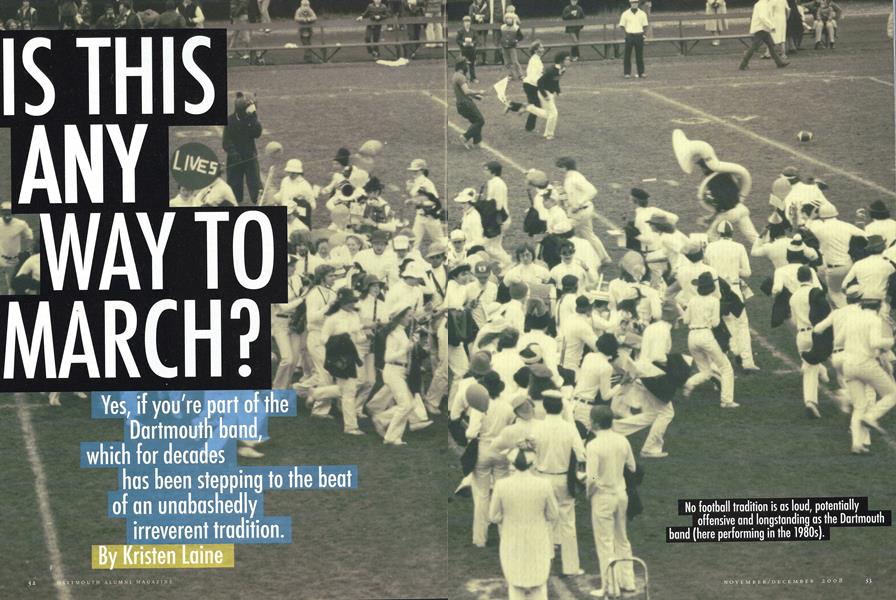

No football tradition is as loud, potentiallyoffensive and longstanding as the Dartmouthband (here performing in the 1980s).

Perhaps playing music,whether on a marching field or in aconcert hall, is not as importantAmerica as it used to be.

Kristen Laine is the author of American Band (Gotham Books),winner of the 2007 L.L. Winship/PEN New England Award for nonfiction.She lives in Orange, New Hampshire.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

COVER STORY

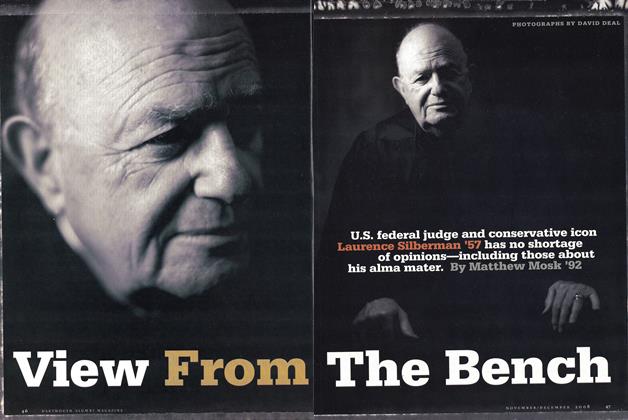

COVER STORYView From the Bench

November | December 2008 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Feature

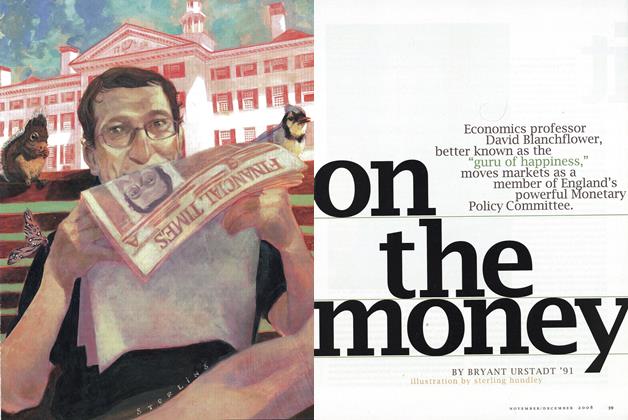

FeatureOn the Money

November | December 2008 By BRYANT URSTADT ’91 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

November | December 2008 By TIM FITZGERALD -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

November | December 2008 By Bruce Beasley '61 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYA Vicious Cycle

November | December 2008 By Latria Graham ’08 -

TRIBUTE

TRIBUTELuck of the Draw

November | December 2008 By Bryant Urstadt ’91

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Great Rip-off

February 1975 -

Feature

FeatureRoommates

SEPTEMBER 1999 -

Feature

FeatureALUMNI ALBUM-30

NOVEMBER 1970 By —BARBARA BLOUGH -

Feature

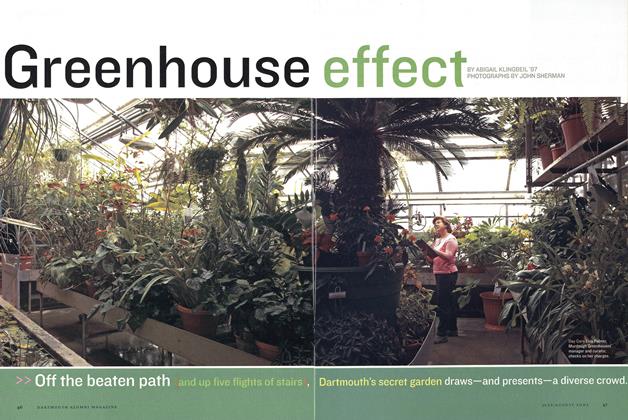

FeatureGreenhouse Effect

July/August 2005 By ABIGAIL KLINGBEIL ’97 -

Feature

FeatureOn a Freshman Trip, the Destination Is Community

MARCH 1989 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureThe Affirming Flame

May/June 2003 By SUSAN DENTZER ’77