THE COMMENCEMENT ADDRESS

IT is always a great pleasure to return to New Hampshire, to visit once again this college of liberal arts that Eleazar Wheelock founded nearly two hundred years ago for the Indians - a great pleasure not merely to visit my many friends here, including President Dickey and Ambassador and Mrs. Ellis Briggs, with whom I worked in Korea, but to pay tribute to Dartmouth and its distinguished sons — for I have greatly admired and worked with several of them including one of America's great scholars, Edmund Ezra Day, who was for many years President of Cornell University, Charles Merrill Hough, one of America's distinguished jurists, and our own able Governor Nelson Rockefeller. And the last but not least of my reasons for enjoying this visit is that my own son went to Dartmouth.

I had tried to persuade him to go to Cornell and in the fall of 1949, when we thought Cornell had a champion football team, I took him to Hanover from St. Paul's at Concord in order that he might see the Indians bite the dust before the Big Red team.

But alas for parental planning - Dartmouth ran away with us, and Cornell lost a son.

I have no way of assessing the true thoughts and feelings on this occasion of the hundreds of other participants in these Commencement exercises, but I can guess.

Those of you in the senior class may wish nothing more fervently than that this last academic and perhaps aboriginal or tribal formality be dispensed with quickly, in order to hasten your departure from an academic world into what we perhaps thoughtlessly call the "mainstream of life."

Other minds may be turned in an opposite direction in anticipation of further studies a few months hence at the graduate or professional level. A very few of you may even be waiting really to hear what your commencement speaker has to say to you.

I am grateful for those latter few, because I look upon this gathering as a relatively rare opportunity to speak across the intangible barrier .of time to younger men of another generation of promise. As Timothy said, "Let no man despise thy youth."

It is true there are no formal barriers to such communication from older to younger citizens, but this is not conclusive.

The fact that we share common newspapers and literature, a common heritage, culture, and society means that we have a formal basis, at least, for an understanding with each other.

I wonder, however, whether all this is, in itself, sufficient for our generation to appreciate the outlook and conceptions of the other. Of course you all remember one of Mark Twain's characters who said that when he was sixteen no man in the county was stupider than his father, but that when he was twenty-three he was amazed how much the old man had learned.

I have not, of course, forgotten, I hope, the attributes of my own youth - principally my resentment at admonition from my elders - but I hope that certain of these youthful qualities of an impatience and wish to investigate new lines of thought, to see greater progress in all fields of human endeavor, to wish to record positive accomplishments in the business at hand, to have an urge to understand things ever more fully, to be more concerned for my fellow man, and constantly to cultivate an instinct for creativity rather than reliance on things past - I hope that all these have become inseparable parts of my nature, as I am sure they are or will be of yours.

THE breathtaking advances of the physical sciences which we are experiencing can lead to conclusions that the philosophy, knowledge, morality, governmental concepts and political science of the past are useless and outdated in this world of space exploration, missiles, and electronic data processing.

Of course, I am not suggesting an undue concentration on the past. I frequently recall that in Washington, at the foot of the steps to the National Archives, sits a brooding figure. Below, incised on the stone, are the words "What is Past is Prologue."

An American family touring Washington asked a taxi driver what the words meant. He scratched his head and said, "That's Washington gobbledy-gook meaning that you ain't seen nothing yet."

The fact that our sojourn on earth is brief, or, rather, infinitesimally short, naturally makes each one of us stop and inquire what it is that we want to be - what it is that we wish to do with our lives, or what it is that will fit most satisfyingly and most suitably within the cosmic backdrop of human environment.

For as Emerson said, "The years teach much which the days never know," and

again, "Be very sure young man you know what you want to be, because you may be exactly that."

It is part of our human condition to attempt to live full, rounded and complete lives and to pass on to posterity this strange and possibly unique spark of intelligent consciousness, which we have received from our ancestors. We have to approach this fundamental responsibility as free men.

In the Olmstead case in the United States Supreme Court, Mr. Justice Brandeis epitomized the American ideal in terms of the relation between our government and each citizen on how we order our lives. He said:

"The makers of the Constitution . . . sought to protect Americans in their beliefs, their thoughts, their emotions and their sensations. They conferred, as against the Government, the right to be let alone - the most comprehensive of rights and the right most valued by civilized men."

This right of self-decision can only increase our obligation to act responsibly. I should like to think that the pursuit of happiness, wealth, fame, career, marriage and family does not deprive any educated men of a sense of deep humility and of a realization that this earth was not made solely for our pleasures.

For this truth remains, that whatever our goals, we will not be true to ourselves if we lose sight of our fellow men, both high and low, with whom - for better or evil — we ineluctably share a common fate.

For our pioneer ancestors, rugged individualism was a great asset. It was fundamental in building our society. But today, quite literally, our very lives in this modern age depend on the helpful cooperation of countless other people, most of whom we do not see or know.

We do not learn unless unselfish men devote themselves to thinking and to teaching. We do not eat unless farmers milk the cows and till the soil, unless middlemen bring the produce to processing plants, and unless distributors, in turn, serve us by delivering it to food markets and homes in town and city.

We are not clothed or housed or transported or kept in health without the cooperative help of governmental organizations, industry, transport, trade, banking, and the many service professions.

John Donne has said "No man is an Island, entire of itself: every man is a piece of the Continent, a part of the maine; if a clod bee washed away by the Sea, Europe is the lesse, as well as if a Promontorie were, as well as if a Mannor of thy friends or of thine owne were; any man's death diminishes me, because I am involved in Mankinde; And therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee."

IN the American ethic, we believe strongly that all our society will flourish most when the talents of individual men, in business, science, and the humanities, are given a wide, free, and imaginative rein. Unlike Communistic, societies, we are not told what to do or think, and dissent as such is not punished even though it be unpopular.

We should think of our freedom, however, as an empirical conclusion based on the specific conditions in which we and our fathers have lived for over some three hundred years on this very fruitful continent. As we look around us at other cultures and other societies, and at the problems of such societies, which are often confronted with vastly different conditions, it is quite evidently true that our approach, however good for us, is not, necessarily the only type of work-able arrangement for all mankind.

It would seem imperative to avoid dogmatism in such matters, to eschew doctrinaire views of how things must or must not be in the proper organization of our society, and to avoid, as U Thant has said, "an obsession with the past."

When the circumstances of our technical environment, at least, are changing so rapidly, when, for example, the individual research scientist, doctor or lawyer frequently gives way to a team or large group of fellow workers, when economic or corporate organizations expand on both national and international levels, we cannot afford to be too cock-sure that the legal, political and governmental ideas, and the institutions of the past are necessarily the best, or even adequate for the present and the future.

Time and space are not annihilated alone in the physical sciences. Individual sovereignty may also come to be annihilated, and the political sciences must keep pace with the physical.

Connected both with this problem of political life and government, and with what I said before about the debt which we owe to our fellow men, is the concept of individual conscience, civic duty, and public service.

Such service can range between extremes - from interesting yourself in a worthy local project, while continuing your daily duties, to abandoning personal fortune entirely to enter the church, a university or high national office.

In my view, none of these things should be considered as affairs separate and apart from our normal lives. On the contrary, they are part of being a whole man and living a complete life.

The business of the state is no longer remote from the personal sphere of any American. And its relationship to us, whether we like it or not, under today's conditions, will grow rather than shrink.

Our duty is not to denounce or to withdraw and to remain aloof - which is largely unproductive and stultifying but rather to think, to work, to contribute, and above all to participate.

WE cannot get the feel of how the Communists negotiate unless we keep constantly in mind that they do not view a world at peace as we do, and that the existence of international tensions is a normal - indeed a desirable - state of affairs for them. In fact, to their way of thinking, it is a precondition to change under the Marxist dialectic that will necessarily persist until they have won the class struggle.

It is our fate - yours and mine both - to be unable to escape the influence and effects of the unprecedented changes, upheavals and revolutions that are sweeping the planet.

For us, the North Atlantic Community, they take the form, primarily, of great technological, scientific, economic and governmental changes and perhaps the initiation of supra-national authorities which will build upon the North Atlantic Council or the European Economic Community called the Common Market and the European Iron and Steel Community.

We of the West look with approval on the end of colonialism, the rise of new and independent governments, the birth of the Common Market, both economically and politically, the change in economic and possibly political relations between England and members of the Commonwealth, if England joins the European Economic Community, and an increase in the prestige and standing of the United Nations and its related institutions.

Countless other peoples are active participants in the great upheavals of our time which involve the disintegration and rebirth of peoples, societies and fundamental relationships.

Communistic agitation, revolutions, conspiracies and the serious problems posed for us by the monolithic Soviet empire or Communist bloc, and by its belief in subversion, infiltration and so-called wars of liberation, while never ceasing to proclaim that it is peace-loving, are but one facet of this more universal phenomenon.

You often hear individuals say that if we could only reduce Soviet fears and if, for example, we would only make a noble gesture such as unilateral disarmament, it would cause the overall tensions to lessen. No one who is familiar with Marxist ideology and with Communist global expectations for the future could possibly believe this. Indeed, this is precisely what the Communists do not want.

To them the termination of the class struggle is not something which can be negotiated with capitalist powers.

It cannot be negotiated, according to Marxist-Leninist theory, because the capitalistic class must be completely liquidated, so that a conference table on peace may turn out to be only one part of the class struggle.

All Americans, in and out of the service of their Government, are vitally concerned with all of these world developments which impinge on our lives and sacred fortunes.

It is important for educated men to follow the outlines of struggles and events and to attempt to lead or at least to understand whether or not these bear any direct relationship to our immediate lives or professional work.

Indeed, it is becoming more and more likely that, at some time during most careers, as individual contacts with both government activities and foreign lands multiply, the connection will become very close.

And this is quite apart from the need for an articulate and well-informed domestic public on the issues of foreign policy.

But all this should not lead us to be too disrespectful of more mundane preoccupations and of the daily need to earn a living, to serve and to serve well. For most of us have to do the daily work of the world. This is very important and essential. Very respectfully, I would counsel against a sense of frustration on this and against allowing preoccupation with the state of the world to become unduly large or to overshadow one's own work and career, unless, of course, the career itself involves dealing with these difficulties.

Frankly, I would urge a long-range and calm perspective of the rivalry and struggle in so many fields between East and West.

We must learn to live with a standing threat and danger to our culture and with the belief that it is not imperative or indeed vital to find a solution favorable to our way of thinking in any given day, month, or year.

To be sure, there is every reason to try to reduce the proportions of the Communist menace, such as we are now trying our best to do, if you will pardon a personal note, in Geneva with the current Disarmament and Nuclear Test Ban conferences. There, we have offered to enter into and are patiently trying to negotiate treaties to stop the arms race and to stop nuclear testing in all environments while preserving the essential peace of the world. We have no illusion that even success in these negotiations will eliminate Soviet ambitions and ideological preconceptions, but it would certainly make our competition and rivalry less dangerous for the future of mankind.

At the same time, however, we should recognize that our main focus must be on preserving and improving our own culture and society, on understanding and helping those who would be friends with us, on helping the less fortunate. Success in these pursuits will go far towards winning the struggle to preserve the concepts and practice of freedom.

Mankind cannot long afford a crusade by any country or group of countries to force all peoples and nations into one uniform Procrustean mold. And rather than undertake any such effort ourselves, we must persist in our own work at home and with our friends in such a way that eventually perhaps new generations of leaders in the Soviet bloc states will come to give up their Communist dialectics and their rather dull, tiresome, and outdated Marxist-Leninist theories about the future which are anything but liberal and anything but helpful in meeting the pressing tasks of the 20th century.

ALL that I have said today presupposes a willingness to work, individual humility, tolerance of human frailties, some understanding of religion, society and history, interest in the affairs of this world, a spirit of public-mindedness, essential morality of behavior, and an interest in what makes us, as humans, tick.

Underlying much of it must be a fundamental and unceasing intellectual curiosity that has stimulated you through the seemingly long years of formal education and training; that will continue to drive or urge you to learn more, to read - especially outside of your own field so you can communicate intelligently with all men — to study, to understand and, above all, to think, I hope, to think analytically, but always with a friendly purpose to your fellow men.

By this stage of your careers, you all have the foundation of knowledge necessary for life, even if many of you proceed to further professional and industrial specialization.

It is even more significant, however, that you should all now be able to think for yourselves, to weigh ideas and arguments critically, to make your own analyses and syntheses, and to arrive at your own judgments and evaluations.

These senses can become dulled if they are not constantly stimulated, used, renewed, and kept alive.

Since all of you have the potential of being leaders in a free society, it is essential that you set up for yourselves the highest standard of excellence of which you are capable. None of us must ever stop striving for greater competence in order to be of greater service.

We must take special care that we rededicate ourselves to the highest goals of our society and that our shared purposes do not disintegrate.

The long-run challenge to us is nothing less than a challenge to our basic sense, both of responsibility to mankind as individuals, and of historical purpose, as a people.

We must prove that free, rational and responsible individuals in a free society - you and I - are both capable of, and worthy of, survival.

Never in our history have we stood in such desperate need of men and women of intelligence and of devotion to ideals.

Of course you must enjoy life as fully as possible. But true happiness does not come from unalloyed pleasure.

The only true happiness comes from losing oneself in some great work or cause for which you are badly needed.

To be needed is one of the richest fcrms of moral and spiritual nourishment.

And so my concluding words to you, as men of Dartmouth, are to think not tco much of self, to avoid the life of too much ease, too much stability. Maintain an interest in all that is going on and live up to the promise inherent in your present achievement.

Never dare not to care. For to live and to have our society live you must care. You cannot afford not to care. To care 's to be a full man and not to care is to be a dull one. And who ever heard of a Dartmouth man being dull?

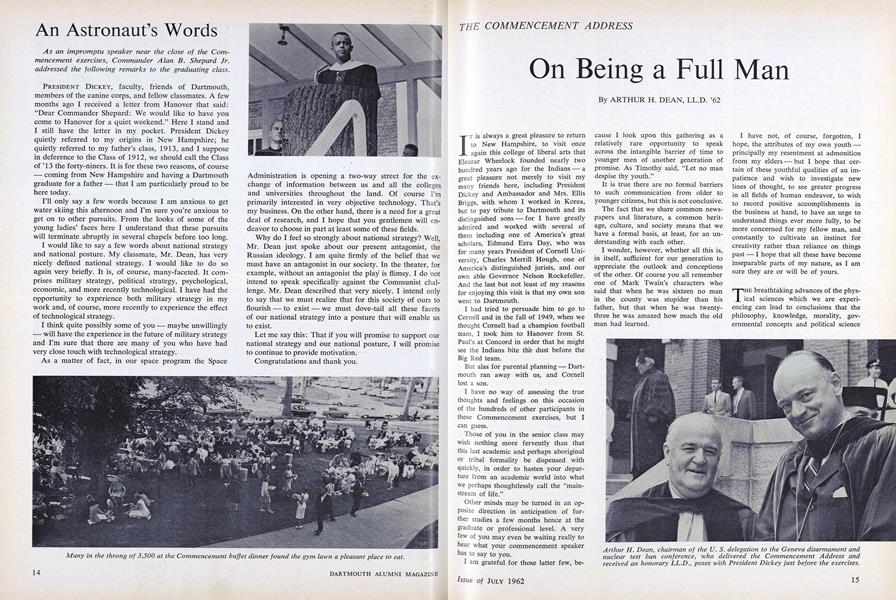

Arthur H. Dean, chairman of the U. S. delegation to the Geneva disarmament andnuclear test ban conference, who delivered the Commencement Address andreceived an honorary LL.D., poses with President Dickey just before the exercises.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Diminishing Citizen

July 1962 By BASIL O'CONNOR '12 -

Feature

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1962 -

Feature

FeatureThe Reunion Week

July 1962 -

Feature

FeatureFive Alumni Awards Conferred

July 1962 -

Feature

FeatureStrickland Heads Alumni Council

July 1962 -

Feature

FeatureThe Greatest Issue: Self-Fulfillment

July 1962 By JAMES T. HALE '62

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryExcerpts from Beverly Sills' Commencement Address

June • 1985 -

Feature

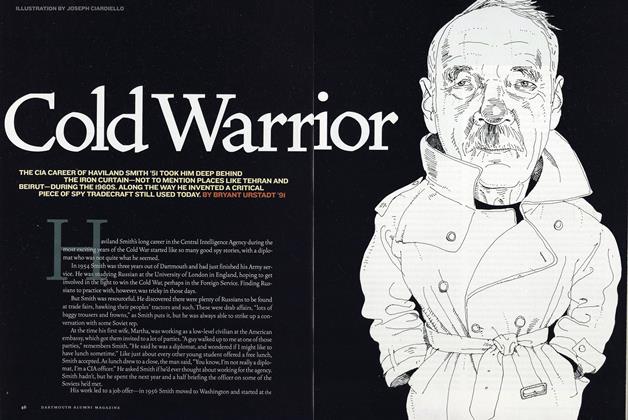

FeatureCold Warrior

Jan/Feb 2008 By BRYANT URSTADT ’91 -

Features

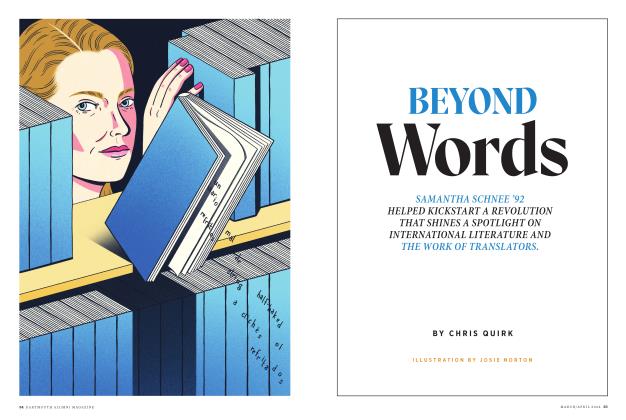

FeaturesBeyond Words

MARCH | APRIL 2024 By CHRIS QUIRK -

Feature

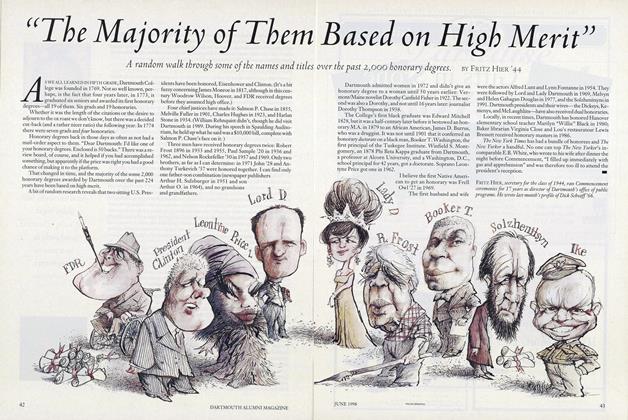

Feature"The Majority of Them Based on High Merit"

JUNE 1998 By Fritz Hier '44 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryOught Ought

NOVEMBER 1996 By Joe Mehling '69 -

Feature

FeatureThe Mold

SEPTEMBER 1996 By Warren Cook '67