A university teacher of Law and English in La Paz has his problems,including a revolution, but still generates enthusiasm for his job.

THE heavy echo of machine-gun and rifle fire continued throughout the city all night and into the morning. From the apartment house where my wife Nancy and I lived with a Bolivian family, we could see very little, and we knew that the curious observer ran the risk of stopping a stray bullet. By noon the firing had ceased and La Paz was quiet except for the airplanes. A few minutes after they appeared we heard their machine guns break into the buzz of their engines, and soon we were all clustered together cautiously watching them through the doors of the sunny balcony as the two old P-51's made repeated strafing passes at a prominent hill a mile away.

When the planes finally left, the radio we'd all been listening to since the revolution seemed imminent announced that the president had left the country and that the military was in full control. Soon Juan Carlos, the young medical student of the family, left to attend the wounded at the hospital. Nancy and I went to our room, grimly musing on the irony of our joining the Peace Corps to get our first taste of war, but at the same time sharing the distress of the Bolivian family at the violence shaking the country. We hoped that the political situation would be eased enough to permit us to get to work at the university.

Of the 12,000 Peace Corps volunteers throughout the world, some 390 are teaching in universities. Nancy and I are among the 45 university volunteers in Bolivia. Our group arrived in La Paz a month before the revolution of November 1964 toppled the regime of Victor Paz Estenssoro.

Bolivia is a country of fascinating contrasts, land-locked near the central west coast of South America. As the newcomer gets off the plane at La Paz, he sets foot on the great Andean plateau, the Altiplano, at 13,400 feet above sea level. He pulls dizzily at the thin air and marvels at the great spread of the snow capped Andes before him. Only the white of the peaks, the brilliant blue sky, occasional flocks of llamas and the bright skirts of their herders break up the stark browns of the rocky Altiplano fields. Yet on the other side of those 20,000-foot peaks are incredible views of the vast jungle floor of the Amazon basin: two thirds of the land area of Bolivia accounting for only 10% of the 4,000,000 population. Descending the 1,000 feet to the city itself, the newcomer begins to see among the adobe houses the bowler hatted cholas or Indian women, and he realizes that this is a country whose people differ as much from the United States as does the landscape.

The strikes and demonstrations by the university students during the 1964 revolution, and their using the university itself as a citadel against the machine-gun attack of the Paz forces, turned out to be only a part of the struggle to be an effective teacher in the university. The struggle begins with soroche, or mild altitude sickness, at the airport, and continues for the next two years the volunteer spends abroad.

THE universities in Latin America play a more prominent role in -urban society than do those in the United States. This is especially true in Bolivia, where 60 to 70% of the population are illiterate peasants, and where the average per capita income is less than $lOO a year. The gulf between the university student and the peasant is enormous, not only in wealth and sophistication, but in almost every way. Most graduates are addressed as Doctor or lngeniero (Engineer) and their status is fixed for life.

There are a multitude of factors which strengthen the hand of the student. Latin American governments concentrate most of the power in the executive, and local government, the judiciary, and the legislatures are usually within the shadow of the president. The president can suspend constitutional rights by calling a state of siege if the political situation becomes explosive. Business and labor as political powers may be weak, divided or uninterested; political parties are often scattered and, in a state of siege, suppressed, as are the newspapers. Thus the university students not only loom large among the relatively few educated people, but by default are one of the few viable political forces. The universities traditionally have had immunity from government control ever since the great continent-wide reform in 1918. The same reform gave the students an equal voice with the professors in electing the rector and the deans and in managing the university — the system of cogobierno or co-government.

A Peruvian educator, Luis Alberto Sanchez, has commented rather bitterly on the role of the university in the class structure of South America. In the March 1965 issue of Cuadernos, a scholarly Latin American magazine in Spanish, he states that the university is a "social bottleneck" and the "only possible source of political and social leadership." Because of the student's automatic prestige and power and the need for his skills regardless of grades, "the student feels himself a mere sojourner or passer-by in his alma mater. . . . The spirit of investigation, the desire for knowledge for its own sake, disappear, and consequently the university languishes. The mistaken concept of the professional university thus predominates, and worse still, the concept of the professional departments (facul tades) above the university itself. . . ." (Each student takes courses only in the facultad or department or school in which he is enrolled. There is almost no interaction among the separate facultades, in all of which, including medicine and law, the students enroll right after high school.)

In Bolivia many of the students and nearly all the professors and deans have a full-time job in addition to and separate from their work in the universities. Except in the facultades of medicine, dentistry and engineering, classes are taught early in the morning, in the evening or during the two-hour lunch break. The great scarcity and cost of books require an increased number of lectures. Thus the law student, for example, may spend 40 hours a week in his job at the bank plus 26 hours a week in classes. (But the La Paz law school enjoys "free attendance," which accounts for a 30 to 40% attendance rate.) The teacher's class load tends to be high, considering his full-time job elsewhere, and thus he has no time for research and little time to prepare his lectures. The professor's pay is an honorarium - as low as $20 a month - and he is perhaps justified in feeling no great obligation to have an impeccable attendance record.

WHEN we arrived in Bolivia, we had had three months of rigorous training in the States. We had classes from 7:00 a.m. to 10:20 p.m. We had six hours a day of Spanish, had done practice teaching, and had a good knowledge of the Latin and indigenous cultures. And, since 25% of our fellow trainees were sent home from the training program instead of to Bolivia, we were glad to have made it. (This is the traumatic process of "deselection," which easily contributes more to the strain of training than do the long hours of classes or exercise.)

The newly arrived volunteer is often surprised to find that the job he thought he had at a given university may no longer be available. He will be sent where the chances seem best for him to find productive work. We suddenly found ourselves staying in La Paz instead of going to Cochabamba, for example. The volunteer's-Spanish is soon put to the test - it's usually up to him to talk to the dean of the facultad in which he hopes to teach. Many of us had a long wait until the school year was over and the next one started before we could begin an official, accredited course.

Our first real problem came as soon as we were settled in our new home. Usually, not long after the intense pressure and dawn-to-well-after-dusk pace of training, the volunteer finds he has more time on his hands than he knows what to do with. It takes time to make oneself known to the dean and the powerful student leaders of the facultad and it takes time to justify and arrange a course, lecture series or the popular cursillo or short course. The contrast between the 14 hours a day of training and the almost complete independence and relative idleness of the first month or so is a bit unsettling.

Adjusting to the politeness of the Latin American is difficult for the practical yanqui. Latin Americans are extremely and yet delightfully courteous. A part of this courtesy is the avoidance of face-toface unpleasantness, and the Latin will also refrain from unnecessary or speculative complication of matters in the same face-to-face situation. These traits combine to form what to the foreigner seems a non-specific, cheerful — and perhaps reckless - optimism. But fortunately the eager Peace Corps teacher learns the system and no longer takes what is meant as a kind assurance for a firm promise.

Let me give an actual example of the struggle. My wife was to give a series of lectures on Bolivian poetry, in cooperation with a government ministry. Everyone contacted was enthusiastic. An official of the ministry was happy to arrange for a small ad in the newspaper. Nancy herself arranged for a lecture hall in the Bolivian-American Bi-National Center, since the university's facilities were already scheduled. With these assurances, she plunged into the preparation of the lectures. As the first lecture drew near, she watched the newspaper with mounting anxiety as day by day the notice failed to appear. Finally on the day before the lectures were to start she went to see the official at the ministry. The official was concerned and compassionate; the notice should have appeared as the paper had been duly informed.

At the office of the paper, Nancy was told that they needed official proof that the ad had been delivered to them. Back the five blocks to the ministry she went, and in the best Peace Corps style not showing her annoyance, got from the official a receipt stamped by the newspaper acknowledging the ad. Then back to the newspaper. Very good, they told her, but you'll have to pay us now for the ad. Without even asking how much this might be, but after some fruitless arguing, she went back to the ministry. Here she learned that the ministry owed a long standing debt to the newspaper, and that it was probably because of this debt that the paper wouldn't print the ad. And the ministry did not at the moment have available the funds to pay for the ad for tomorrow's lecture.

Word of mouth publicity brought twenty people to the first lecture. Another unforeseen difficulty made itself known a few minutes before the lecture was to start. The janitor shuffled in with a few Coleman-type gas lanterns, pumped them up and set them ablaze. Nancy had for gotten that every other night - the nights of her lectures - the electricity was shut off in that neighborhood. La Paz depends on hydroelectric power, and the long dry season requires rationing of electricity.

By the next lecture, at the suggestion of another official at the ministry, Nancy had managed to get a mention of her lectures in the society page, and had almost one hundred in attendance. In spite of the hiss of the lanterns, the lecture was a success. The next day, however, brought still another calamity: the fighter planes again took to the air. The junta had exiled the key leftist leader, Juan Lechin, in order to bring the nationalized mines under firmer control; the streets were filled with demonstrators, the road to the airport was blocked by sniper fire. The Bi-National Center, along with many businesses and stores, prudently locked its doors. The government called a state of siege, and Peace Corps volunteers were advised to stay home after dark. When things calmed down a bit after several days, Nancy found another hall (the Center now having other previously scheduled events) and resumed her lectures — but without any publicity because now all the newspapers were on strike. About fifteen attended the third lecture, forty the fourth and fifth.

Nancy's difficulties were unusual, but only with regard to the actual gunfire in the streets. More common aspects of the struggle are student strikes and meetings that interfere with classes, university politics, rigid curricula and dependence on lectures, the lack of texts, the often inadequate preparation in the high schools, vacations and numerous holidays, and the casual approach to learning as indicated above by Sanchez.

The struggle sometimes approaches the bizarre: an lowa girl teaching brass instruments in the La Paz symphony could barely eke out an octave from her trumpet during her first weeks at 12,500 feet above sea level, and twice she fainted away at rehearsals. Illness is now and then a problem in spite of the excellent medical care the Peace Corps provides.

THE university volunteer, like his rural colleagues, generally lives with a Bolivian family, at least for the first few months. Among the many advantages: constant practice of Spanish, friends, familiarization with the culture, and not having to shop or cook. These last are difficult where there are no supermarkets and few refrigerators. More than a few volunteers have trouble adjusting to the very different food, such as chuño, a blackened potato that has been alternately frozen, thawed and stamped on in the process of drying. The volunteers who live in the Amazon region often swear they'll never look at another banana or grain of rice.

The program of university volunteers by and large is winning its hard-fought battles, in spite of the fact that at the conference last spring of the university volunteers in Bolivia, no one was too surprised to find the group considering the question of whether or not the university program should be continued. Social change, without which real economic change is impossible, is a painfully slow process.

There is a severe shortage of good engineers and scientists in Bolivia, as in most developing countries. Training students abroad is not the answer because too often they don't come back. So the volunteer with his solid U. S. training, able to teach full time, is effective. In the historic town of Sucre, for example, there is a group of three volunteers practically carrying the whole load in chemical engineering. One has a Ph.D., another a Master's, and the last a bachelor's from M.I.T. It is the only chemical engineering department in the country's seven universities.

Most of the engineer volunteers here find that their greatest task is to teach problem-solving. Their students have had very little practice in this important aspect of their profession. The same is true in other parts of the educational system. The law school examinations, for example, are largely tests of memorization and amplification of sections of the course outline. The volunteer finds himself bringing a fresh, imaginative approach to both study and teaching methods, and the students are grateful.

Almost every volunteer throughout the world teaches English at one time or another. The demand is insatiable. A knowledge of English can mean a scholarship to the U. S. or other countries, it can mean a better job here in Bolivia and greater professional competence, especially in medicine, because of the paucity of Spanish journals.

Many volunteers meet very real needs. The trumpet player who fainted twice is, so far as she knows, the only professional teacher of brass instruments in the entire country. The three artist volunteers are working long hours in the universities, secondary schools, and among the carnpesinos, teaching pottery, puppetry, drawing, painting, and crafts. Nancy is making progress in expanding balanced literary criticism and, much to her surprise, is considered a professional critic, with some of her work published in the literary supplement of a La Paz newspaper. Another volunteer is helping to set up the country's only computer.

My own work has been varied, challenging and sporadic, most of it in seminars and occasional public lectures on comparative law, in addition to 8 to 12 hours a week of English teaching. I represent the Peace Corps on a minor Embassy committee, advise volunteers on their income tax, and am writing a study on Bolivian legal education.

BECAUSE volunteers work almost entirely within the institutions of the host country, usually live with and earn no more than their counterparts, the volunteers enjoy (and perhaps too jealously guard) a better reputation than many other Americans working abroad. Urban Bolivians are astounded at the adaptability of the community development volunteer who willingly lives for two years in villages where they wouldn't willingly spend one night. Volunteers are often the first Americans a Bolivian really knows, and their mere presence cuts through the vague reputation of the monolithic, distant economic power that is the United States. The volunteer becomes a friend.

Probably the greatest reward for the volunteer, even greater than his personal contact, is his new perspective on the world. No other job, except perhaps that of an anthropologist, can give one so profound a basis for comparison of two cultures. We see the United States in a different light. Its commercialism, its citizens' lack of concern for foreign affairs, are disturbing; but at the same time the American knack for compromise and the country's efficiency, excellence in education and great and varied political and industrial achievements, are for the first time brought into sharp perspective. The reaction of a volunteer as he leafs through a copy of the New Yorker is wonderfully predictable. Its advertisements show us the voracious consumption of luxury goods in the United States that we never quite appreciated at home.

The new perspective doesn't stop with the comparison of Bolivia and the United States. By reading, discussions and travel, the volunteer soon realizes that the problems of Bolivia are shared by most of the other countries of the world. The subsistence level and peasantry, the small middle class, the insufficient job training and education, the political and social status of the students, the vicious circle of the underdeveloped economy: all are found to a striking degree in Africa, Asia, the Near East, as well as here in South America.

Volunteers now and then like to poke fun at the Peace Corps reputation for wild-eyed idealism. We received a letter recently from a friend of ours serving as a Peace Corps volunteer in Africa. He added to his letter: "P.S. Do write soon, you noble Americans who are courageously building a new and better world for all of humanity!"

Most of us joined the Peace Corps from a mixed desire to be of use in developing countries, to seek adventure, to travel, to learn a language, to gain knowledge of another very different world, and perhaps to get away from something. Some of these motives are very similar to those that inspire men to go off to war. As the psychologists made clear to us in training, the realization of these motives makes us more credible to the people we work with. The real idealism is to be found in the readiness to sacrifice two years from young careers, the desire to tackle a tough job, and perhaps in a certain liberalism. Though of course politics has nothing to do with selection of trainees, it is interesting that in our group of 85 in the summer of 1964, which included both university and public health trainees, only one favored Goldwater.

In short, the experience has been invaluable. I join the ranks of those who say that the impact of the Peace Corps as an agent of economic and social development is exceeded only by the insight into foreign cultures and affairs gained by the volunteers, and thus by the United States.

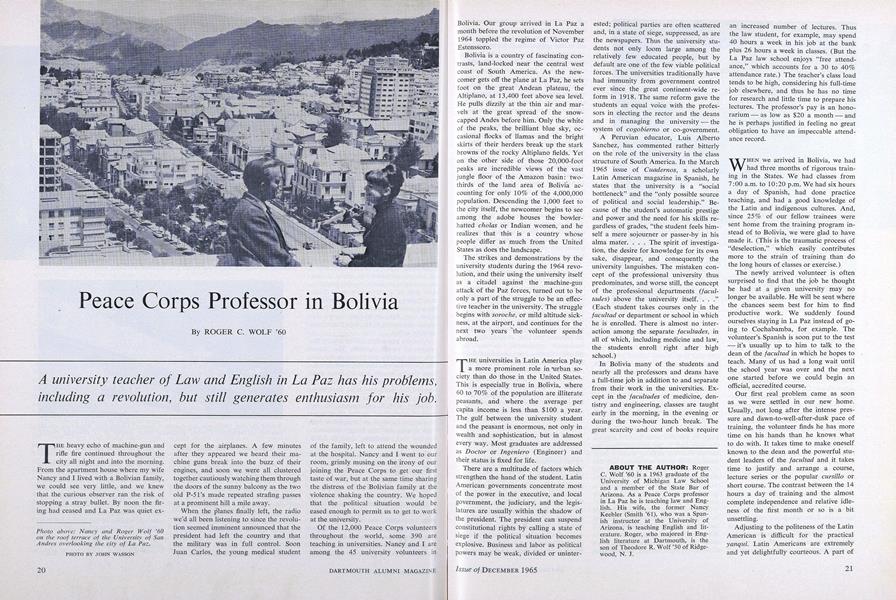

Photo above: Nancy and Roger Wolf '60on the roof terrace of the University of SanAndres overlooking the city of La Paz.

Indian women selling fruit, soft drinks and soap on the outskirts of La Paz.

Armed "campesinos" coming to the aid ofthe Paz regime in November 1964 uprising.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Roger C. Wolf '60 is a 1963 graduate of the University of Michigan Law School and a member of the State Bar of Arizona. As a Peace Corps professor in La Paz he is teaching law and English. His wife, the former Nancy Keebler (Smith '61), who was a Spanish instructor at the University of Arizona, is teaching English and literature. Roger, who majored in English literature at Dartmouth, is the son of Theodore R. Wolf '30 of Ridgewood, N. J.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureBaker Holds the Key

December 1965 By JAMES W. FERNANDEZ -

Feature

FeatureA Major Geological Discovery

December 1965 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

FeatureA Football Victory Hanover Will Never Forget

December 1965 By R.B. -

Article

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

December 1965 By ERNIE ROBERTS -

Article

ArticleThis Mother of Seven Dartmouth Sons Read Every Book in the College Library

December 1965 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Article

ArticleThe Campus Examines Public Issues

December 1965 By LARRY K. SMITH

ROGER C. WOLF '60

Features

-

Cover Story

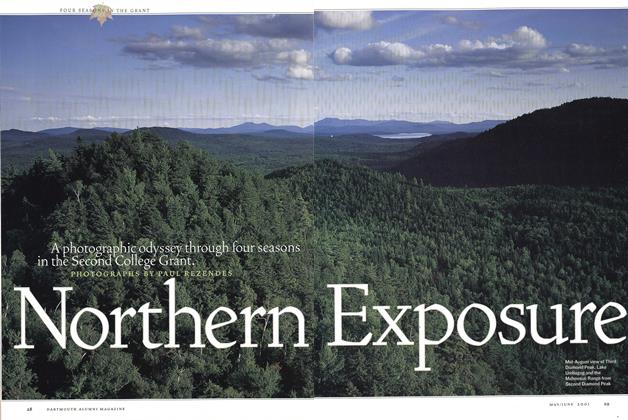

Cover StoryNorthern Exposure

May/June 2001 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryINDIAN SYMBOL FELT

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

FeatureThe 190th Commencement

JULY 1959 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

FeatureHow Public Is Music?

February 1960 By JAMES A. SYKES -

Feature

FeatureMen in Uniform

Sep - Oct By LEE MICHAELIDES -

Feature

FeaturePresident on Trial

JAN./FEB. 1979 By Marilyn Tobias