Quo Animo ("By what mind, with what intent" - hereafter Q.): Driving a car or shaving or falling asleep, haven't I heard you somewhere before?

Alter Idem ("Second self" - hereafter A.): I have many disguises: conscience, inspiration, elan vital, the inner check, Monday morning quarterback, the brass-tack salesman, echo, the private I. You are asking my help?

Q. What can you tell me about the general use of higher education? Please observe that I emphasize the adjectives.

A. Something - just possibly. I have lived in three different college towns.

Q. A man might live in Camembert, and not know how to make cheese.

A. I spent four years in a college.

Q. And then?

A. I hung round for another forty just to see what I had got out of - pardon me - derived from it.

Q. You have steeped yourself in Alma Mater? You must reek of the place!

A. I am unaware of that. Apart from accurate estimates of my true vocation, I have been taken for a chess player, an orchardist, a reporter at large, a patent lawyer, print collector, past president of a narrow-gauge railroad, editor of a defunct quarterly, and a dealer in movable type. It is only in Greek and German restaurants that I am sometimes called professor.

Q. You know you are not a professor.

A. In extended argument, some of my friends will say that I missed my calling, though not by much. No: lam a lifelong student. Do you remember what James Bryant Conant said in 1936, at the time of the Harvard Tercentenary? "He who enters a university walks on hallowed ground."

Q. But a college or university surely is not life.

A. Perhaps. But at least it is a stage; and on the stage, says Thornton Wilder, "it is always now." The only difference is that on Broadway or in London you have the same actors in different dramas; in college you have successive actors in the same dramas. Take your choice.

Q. All right; you have taken yours. Am I correct in suspecting that you are puzzled by the current popular image of the college? We all know what that is: the passport to a better job - where "better" is an unrequited comparative; a package deal of contacts-that-will-help-me-in-later-life, organized or spectator sports, bull sessions, desultory reading, dates unlimited, freedom of supervision, and the technical mastery of an early warning system against the examiners' attack. College is also a place to go back to, a football team, a target for stray criticism, a box of dreams in camphor, an experiment in architecture, a prestige name to boast of, and annual-giving Fund.

A. This isn't everyman's indictment, even among the young.

Q. I called it the popular image: largely in the minds of the unacquainted.

A. "All music [I am quoting Whitman] is what awakes in you when you are reminded by the instruments." When the mind awakes, the student - and then only - has a right to be so-called. He has found himself.

Q. Has it ever crossed your mind that a Maine guide's license - not to be come by lightly - is in one respect worth more than the A.B. degree? It is, in fair part, a guarantee against getting lost. The A.B. guarantees nothing.

A. Think that through. Anyone who does not commit himself to being lost in college will never know what he's really there for. And what is he, may I ask you, if not for the joy of discovery?

I take the red lance of the westering sun And break my shield upon it; who shall say I am not victor? only that the wound Heals not, and that I fall again.

Something to tilt against: something to win from or win in, and lose to and win from or in again. It matters not whether the light breaks through in poetry, linguistics, acoustical theory, choral composition, Sanskrit, engineering, steroids, heavy water, or mycology. Call it revelation, if you like. It may tremble in the turn of phrase on a teacher's tongue; it may lie hidden in an oil or water color hanging in the college museum; it may settle as yellow substance at the bottom of a test tube, or break forth in a single chord of Palestrina. G.M. Trevelyan has spoken of "the poetry of handling old Mss. which every researcher feels." Harlow Shapley, the astronomer, has said that on opening a book on mathematics he was sometimes moved by the same emotions he had when he entered a great cathedral. Some day (and I regret to predict it) there will be a monitor station, with a dean in charge, in every college in the land: a light will flash, and Fresh- man X will be credited with his awakening. "Three years, Mr. Y, and I must inform you that as yet your light has not come on." But enough of that! To be young and in college, if only the young and in college knew it, is looking up at the night sky, mobile under scattered clouds, when no two stars are of one constellation. Now and then the heavens will open wide; but oftener not. Consider Mr. Frost's poem, "Lost in Heaven," from which I draw my star-talk:

Let's let my heavenly lostness overwhelm me.

Q. That seems an elaborate metaphor for one who frequently quotes Ellis, what? "Be clear, be clear, be not too clear." In the popular image, of course, there is no room for footnotes like the one that Christopher Morley's father, Professor of Mathematics at the Hopkins, appended to a tough examination paper he had set. "If an exact answer does not suggest itself, an inspired guess will not be without value." To the image makers, college is ...

A. Colleges, if we adhere to the prefab image of so many young matriculants, would feed the dream direct to the computers. But this will never be, make no mistake; for somewhere on some campus there is always coming up an Emerson, Webster, Brandeis, Millikan, Jane Addams, Thurber, Cather, Cushing, Carson, Salk, De Voto, or Marquand who find exactly what they need, flourish often in creative loneliness or at variance with tradition. In the renewal of achievement, they will mend the leaks in the true legend of what a college is. And please to note here that the legend is always better than the popular image, just as in poetry the metaphor is stronger than the simile. Observe with pleasure that the legend is always of thecollege. Longfellow of Bowdoin, for example.

Q. We are not forgetting (a) that the awakening process frequently occurs at the grade-school level; (b) that for many remarkable individuals college was and remains outside their ken: witness Franklin, Whitman, Mark Twain, Winslow Homer, Edison, Burbank, Hemingway.

A. We are not forgetting that to the early-awakened the college is a paradise. For the writer and the artist it helps provide an intelligent, widening audience. As to inventors: it is unlikely in the future that the great ones will not be trained in universities or technical institutes. It is quite a day's journey to the frontier of science.

Q. You will grant that in spite of inflation, internecine war over who gets whom among the teaching giants, and the magnified problem of balance between the humanities and the sciences - our colleges survive as islands of light across the nation. The young ones struggle toward accreditation; the old ones to keep their place, or better the peck order in achievement and endowment. At the same time they are beginning to function as the cultural centers of their communities and sometimes (as in particular with certain state universities) of their states. They are the new patrons of the arts - and of the sciences, too; on the air and on the screen and on the public platform. Faculty, students, facilities - all are variously involved.

A. But still the tragic failure of our colleges involves the average alumnus - and I am using the masculine by grammatical convention. He is like a three-stage rocket: the first takes him up through the twelve grades into college, the second takes him through college and even through graduate school; but the third one frequently fails to ignite, or flames out before he goes into orbit. "All the little time I have been away from painting [wrote Edward Lear in 1859, when he was 47] goes in Greek. ... lam almost thanking God that I was never educated, for it seems to me that 999 of those who are so, expensively and laboriously, have lost all before they arrive at my age - and remain like Swift's Stulbruggs - cut and dry for life, making no use of their earlier-gained treasures: whereas, I seem to be on the threshold of knowledge."

Q. Well. ...

A. Let me say it for you. The average men or women of thirty-five, graduated from college, many of them having sensed the landfall or having seen the beacon; well aware of benefits - of doors that opened, of books that pointed on toward other books, of speculation premising delight - can only say with Coleridge: "My imagination lies like a cold snuff on the circular rim of a brass candlestick." If they learned to haunt old bookstores, did they continue the habit until they had put together a self-selected library of two or three thousand volumes? Very few of them. Do you think they really know and value and reexamine the heart of a dozen great books? I strongly doubt it. Do they read twelve worthwhile books a year? I doubt that, too - more strongly. When they learn that Johnny can neither read nor write, do they ever stop to listen to the sound of their own speech? read the letters which they themselves have written? think before they parrot back cliches that figure like I'm telling you? Have they acquired a modest judgment respecting prints or water colors, etchings, aquatints, or wood engravings? In most cases, no. Do their homes and offices reflect in taste what a hundred dollars or so a year for fifteen years would gratify? Make a mental check of the next ten of each you visit. Music I except because the stereo mind was likely developed independent of the college years; and this is the one art truly catholic in our time. As for the drama, I cannot even guess. It is surely strong in the colleges, and the stock companies (freshly stocked) are witness to that strength. I am minded, rather, of Dorothy Parker's account of a Benchley-Ross exchange in the New Yorker office. "On one of Mr. Benchley's manuscripts Ross wrote in the margin opposite 'Andromache', 'Who he?' Mr. Benchley wrote back, 'You keep out of this.' " Perhaps I should have kept out of this dialogue.

Q. Not at all. Someone may shift Mr. Benchley's "Who he?" to plain "Who? Me?" Someone who thinks that the ethos of college is still with him; who is rusting on his undergraduate laurels for whatever they were worth; who has neither found the time nor taken the trouble to form an exemplary taste for anything - in anything. You remember what a character in H.M. Pulham,Esquire said? "On leaving college [twenty-five years ago] I started Gibbon's Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire and Nicolay and Hay's Lincoln. I am still working on them in my spare time." Amusing, yes; but sadder than amusing - and pathetic in its sadness.

A. The prevailing notion is that one passes through college on the way up - toward success, achievement, or some satisfying approximation. Under this assumption, the college appears as a point - a little gold star — on the curve: about twenty-one years out on the X (horizontal) axis. Interpretation? Enter, exit the college. Agreed? No, that is wrong. It is, in truth, the basic tragedy. Ideally the college remains a function of the curve and not a point upon it - a determining factor of its ultimate character or direction. For example: if against the X life-span you plot the vertical Y as the sum of special knowledge - what the individual knows in detail respecting many subjects - the peak of the curve may well remain at twenty-one, since after graduation most diversified special knowledge tends largely to decrease. An honors student - a good student, for that matter - may never know again so much in several fields as he does in the final week of senior examinations. On the other hand, remembering Whitehead's disclaimer anent the value of "scraps of information," Y may (and should) assume a much nobler role - intellectual power, for one. Granting that, then, any moment on the curve will reflect the increasing functional share of the college in the value of the individual to himself and to society. For want of a better name, let's call that function "the habitual vision of greatness."

Q. Since many have a natural distaste for graphs (graphobia), why not choose the river symbol? The curve suggests a river.

A. Bear in mind that the curve (ideally) runs up, the river down. But fortunately the river runs toward bigger and even better things - the fertile valley and the sea, for instance. You may flow with it or let it float things past you, as you wish. Poets frequently stand close to fishermen in thought. "Poets," says Archibald MacLeish, "are always wading and seining at the edge of the slow flux of language for something they can fish out and put to their own uses." Let me argue, then, that if we think of the college as a river in the slow flux of being, we shall always find something to fish out of it. Erstwhile students of such famous teachers as Churchill of Amherst, Winch of Wesleyan, John McCook of Trinity, Woodberry of Columbia, Strunk of Cornell, David Lambuth of Dartmouth, Bliss Perry and Copey of Harvard have done such fishing and such finding. To this day I remember my high school teacher of German - rich in the culture of the Jewish race - shaking her finger at us, saying: "Never let a day go by without looking on three beautiful things." Trying not to fail her in life meant trying not to fail myself.

Q. Are you suggesting that it is only between the best teachers and the most responsive students that this flux of being can be perpetuated?

A. Not at all. The great critic, George Saintsbury, said of Oxford: "For those who really wish to drink deep of the spring - they are never likely to crowd even a few Colleges - let there be every opportunity, let them indeed be freed from certain disabilities which modern reforms have put on them. But exclude not from the beneficent splash and spray of the fountain those who are not prepared to drink very deep, and let them play pleasantly by its waters." Almost a hundred years ago, Andrew Preston Peabody, Acting President of Harvard, pled publicly for all those of "blameless moral character" who stood scholastically at the bottom of their class. "The ninetieth scholar in a class of a hundred has an appreciable rank," he said, "which he will endeavor at least to maintain, if possible to improve. But if the ten below him be dismissed or degraded, so that he finds himself at the foot of his class, the depressing influence of this position will almost inevitably check his industry and quench his ambition." Today, under the pressure of increasing competition, some reasonably good minds will function somewhere near the foot of every class. Provided that they see,the light, who else will be more avid to enjoy what Justice Holmes has called "the subtle rapture of a postponed power"?

Q. Perhaps it is largely the city which stands between the college and the disciples. Within its arcane babel it is hard to distinguish echoes from that other world. And with days pressing in and time running out — in the city, in traffic, in confusion - doubly hard to remember that the physicist has room for Andrew Wyeth, the classicist for Tarka the Otter, the Bauhaus architect for Walden, the musicologist for Freya Stark, the masters of Univac for the sight of polygonella articulata burning in the autumn wind by sandy edges of expressways into Maine, the floundering economist for spotting Indian watermarks in southernmost Wyoming.

A. No wilderness bewildered Academe a hundred years ago; but megatropolis is something else again. Man on his plundered planet, in his silent spring, must come to terms with nature long before his packaged plankton supersedes the boxtop cereal. The colleges, backwater stations as they once were called, are all we have here on the last frontier. Alumni who support them ask and take too little in return. It is their own fault, to be sure. As Samuel Butler could lament that there was (and is) no Professor of Wit at Oxford or Cambridge, so one may deplore - why not? — the lack in all our colleges and universities of an Emerson Chair of the Spirit. You may take that small suggestion indirectly from Matthew Arnold. And a Henry Thoreau Chair of Self-Sufficiency. "It is time that villages were universities, said Henry. The time is coming when they will be. Better than that: when man will be a college to himself, not least of all lest "things grown common lose their dear delight."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDARTMOUTH IN THE PEACE CORPS

May 1963 By Clifford L. Jordan Jr. '45 -

Feature

FeatureLewis Dayton Stilwell (1891-1963)

May 1963 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

May 1963 By WILLARD C. WOLFF, WILLIAM T. WENDELL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1911

May 1963 By NATHANIEL G. BURLEIGH, JOSHUA B. CLARK -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

May 1963 By CARL MAVES '63 -

Article

ArticleHANOVER DOGS 1963

May 1963 By ALLEN R. FOLEY '20

Features

-

Feature

FeatureStudents

June 1980 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryWarming up for 50 years: The yeast of elderly innocence

JUNE 1982 -

Feature

FeatureHow I Overcame Lingering Thoughts About The Immorality Of Computers, Edited A Newsletter And Changed My Life In One Week ...

December 1987 By Jack Aley '66 -

Feature

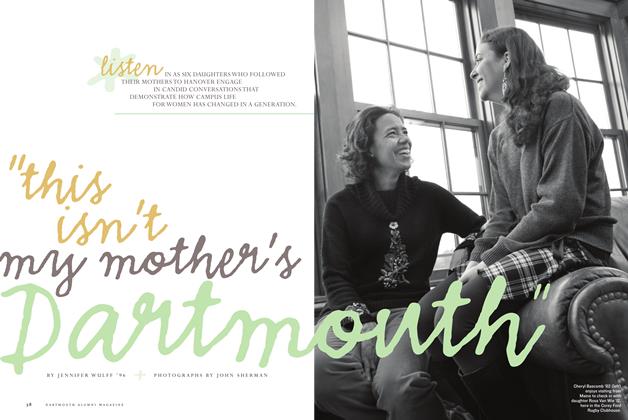

Feature“This isn’t My Mother’s Dartmouth”

Sept/Oct 2010 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Features

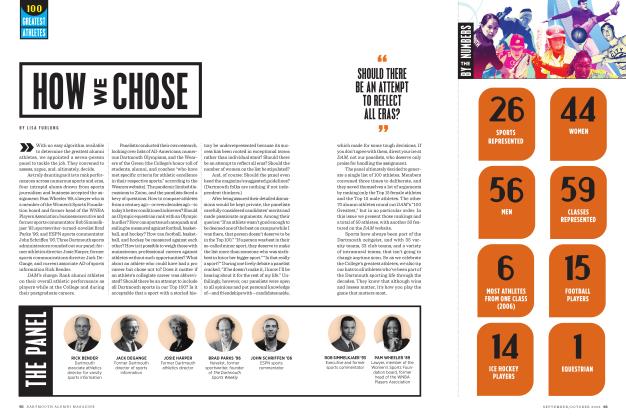

FeaturesHow We Chose

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2022 By LISA FURLONG -

Feature

FeatureHow the Dutch Handle It

JUNE 1973 By Robert D. Haslach '68