Professor Stewart's talk to the Class of1967 assembled in Spaulding Auditoriumwas the final event in Freshman Week.At its conclusion the class rose as a manto express approval, and several scorekept Professor Stewart on hand for twohours more in an informal give and take.This edited, and much shorter, versionof the talk was taken from a tape madeat the time since Professor Stewart spokefrom notes only. The Dartmouth Alumni Magazine regrets the lack of space toprint the address in its entirety, includingpoetry. The talk began with ProfessorStewart reading a poem.

THAT POEM is called "Court-martial," and it's by Robert Penn Warren. I'll tell you why I read it. This boy on a summer day down in Tennessee (it was Warren himself) sees his grandfather and the isolated farm as dull, peaceful, sure things, and he thinks he knows about the truth. He thinks he knows what really happened in the Civil War and so he plays a game of correcting his grandfather's mistaken history. Suddenly his secure little world is shattered. His grandfather becomes real to him as a person, as a man who has participated in violence and is now haunted by guilt, and the edenlike existence of the little farm is shattered by a vision of evil: the Bush-whackers and the man who hung them. The actual world has crashed through and now the boy has to live in it and has to live with it. He has taken a long and irreversible step toward manhood.

As you well know, you too have taken a long step toward manhood. You've put your foot forward in the darkness of the unknown and wondered whether the ground would bear your weight. Oh, I know. It's the end of Freshman Week and you're all very gay and very blase. You're bored with tours and tests, and like the boy in the poem you pretend you know the truth. Or if you don't know the truth you soon will. But somewhere at the secret core of your being you're probably pretty bewildered and anxious and uncertain, although you don't like to admit it, because that old familiar world that you've lived in for so long is gone, gone for good. And suddenly for you, too, the world - the vast, confusing, glorious, terrifying world that men live in, sometimes violently and sometimes joyfully, that world is real. And it is there, which means you've begun your liberal education.

Why do we call it a liberal education? Far back in Greece and Rome it was thought that only free men were entitled to study the intellectual things and problems of moral excellence. These were the goals that Plato and Aristotle in their writings defined as the proper ones for such an education for such men. Later on in the days of Queen Elizabeth and Shakespeare the distinction was made between education in the liberal arts, which was for gentlemen and for leaders of society, and training in the craft arts, which meant acquiring skills of doing things to earn a living. The proper study for plebeians was, you know, carrying furniture and things like that. Gentlemen, read "upperclassmen," were free to meditate and make choices that were based on moral and aesthetic discriminations. These were the men who were concerned with what men aspire to and the values that men live by. The plebeians, like freshmen, were just supposed to take directions from them. Today we have abandoned this idea that only members of some superior hereditary class are concerned with values, that only they are deserving of education for intellectual and moral excellence. But we retain the notion that the study of the values that men live by is the rightful pursuit of free men. Hence, liberal education.

Mark Van Doren put the matter very well when he said this education that you are now entering upon "is called liberal because of the faith that now the student becomes free of his childhood and free therefore to think and feel as an adult. This is his initiation into humanity, as humanity has always been known. Man's distinguishing feature is his intellect, his reason and his art, and to be possessed of this feature is to be made free as only men are free."

But there are a lot of people who can't bear to be made free as only men are free. Because this discovery of the ambiguity and the complexity of the world and of life is a stunning experience, whether it comes to a small boy on a Tennessee farm suddenly discovering that his grandfather had hung men, or whether it comes to us in the seemingly simple and easy matter of going away to college - emotionally it's anything but that. We often feel that our elders have betrayed us, and in a way they often have, because they have encouraged us to think of adults as noble and wise, patient and courageous, and virtuous to an impossible degree, and so in our anger and our anxiety we may turn upon the adults who have taught us this impossible lesson. We feel they have misled us and we turn upon them and judge them with a terrible harshness. Then we are overcome with shame because very often we are turning upon those whom we love most.

ONE OF our most natural reactions to the situation is to look around for some substitute, some person or some group or some institution which is wise and confident and powerful. We want this substitute in order to keep life clear and simple because now it's beginning to become problematical and complex. We want this substitute to tell us how to behave and give us quick answers on what is right and what is wrong. We want this substitute, if necessary, to take over the burden of responsibility for making decisions which is part of the burden of being a free man. We feel very lonely, unsure of our powers, and we're shy beneath the bold appearance we wear during Freshman Week or on other such occasions as this, so we oftentimes wrap ourselves up in the anonymity of the institution and give it our fanatical loyalty. We surround ourselves with all sorts of symbols of belonging to something we hope is strong and sure. We wear caps; we buy beer mugs, jackets with the name of the college on them; and we put on uniforms.

The leaders of the emergent nations often understand this very well. They realize that the changeover of a revolution or the founding of a new nation has shaken the people in their old way of life and the familiar symbols, and one of the ways of making them manageable, one of the ways of giving them hope and belief, is to give them a uniform to wear, something to which they can give quick and easy (unthinking) fidelity. In this situation we watch others, and we assume a uniformity of dress, mannerisms, slang. Oh, heaven help the poor fellow who uses high school slang in a college situation. We're ruthless toward the men that don't conform. Why? Because they threaten the stability of this thing to which we have attached ourselves, and because the men who don't conform remind us of our fear of what might happen to us if we don't conform. In our anxieties we take it out on them and are pretty rough on them, and just when we are most vulnerable, just then we are likely to find our beliefs most deeply challenged.

We attempt to join organizations that promise protection to this challenge. They promise to fight the threat of change, and they come to us with outstretched arms and with eyes wide with alarm. On their lips are sacred words: Mother, Flag, Freedom, God, and Yale. They claim to have it all worked out, you see: it's very simple. There are the good guys and there are the bad guys. Quick! Join up with us and prove that you're a good guy. The followers of Kennedys and the ADA blame all our troubles on the followers of Mr. Goldwater. The followers of Mr. Goldwater blame all our troubles on the Kennedys and the ADA. The Segregationists claim it's all the work of northern Communists. Now, most of these "Youths-for-this, that, and the Other" organizations are harmless enough, but we've seen this devil theory before. Hitler blamed all of Germany's troubles on the international Jewish conspiracy. Castro is getting a lot of mileage out of blaming all his troubles on us. But these groups and their leaders provide something that many people long for. They'll do the thinking for you. They'll carry the burden of responsibility. They'll identify the enemy. They'll give you uniforms. They'll give you slogans. They'll give you defiant songs. They'll give you the excitement of mass movement. All they ask for in return is that you give up your freedom of thought and choice, which is what many of us are very eager to do. It's too great a burden for us to carry.

That's one way of protecting ourselves from this uneasy situation. Now, there are other ways. We can protect ourselves by making up all kinds of stories, little dramas of ourselves, and they create very flattering roles that we act out. The bluff, frank, hardy, friendly man's man type, you know. Or the cool, smooth, slim, well-tailored young executive on the way up. Or the lean, slit-eyed, tanned, quiet, faintly-remote jet pilot type. Then there's the model that's very popular at M.I.T. that I observed in my year off. This model is pale, slightly overweight, wears heavy black, horn-rimmed glasses, carries a very battered looking briefcase, and is always late for his bus. Now, merchants and advertisers understand this very well, and they sell us all sorts of things we need to build up this role and act out our parts - wool shirts and climbing boots, expensive guns to hang on our walls, waste baskets with liquor labels all over them to show how sophisticated we are, marvelous cigarettes to build up our virility.

So we settle down to 350 h.p. buttondown, split-level, high-fi, deep-freeze, plastic-covered, electronic, ail-American banality. We're free from freedom and still living in childhood, encouraged by all the advertising in the slick sentimental movies and the TV programs. We actually think this is being alive; that this is being human. But it can't last! Because all of us, all of us that have the stuff of manhood anyway, all of us have a drive towards self-realization that is more powerful than our longing for childhood security. And even those that are nearly dissolved in the trivia of existence, whose minds and spirits have been very nearly eroded away by boredom, they too have their moments of self-doubt.

MOST of us don't get into that sorry plight because we take up the burden of freedom. We accept the fact that before we can stand together in any kind of meaningful organization we have to be able to stand alone, to accept the responsibility to think and feel as adults without the protection, without the permissiveness that is extended to children. We stop looking back to the Garden of Eden and begin the long, agonizing and difficult, sometimes terrifying and sometimes very joyous, search for ourselves. And there are three stages to this search. The stages emerge and melt into one another and never, never finish. The first is learning to accept the nature of the real world that is there - that's the boy's problem in the poem. It shattered his little dream world and now he's got to learn what the real world is and how to live with it. This means confronting all the horror and the beauty and delight. This means coming to terms with the fact that you can't run away to childhood, you can't run away to fantasies, you can't lose yourselves in mass movements, you can't go to some new place, make a fresh start with a new name because nobody knows you.

The second stage is learning to know and accept human beings, accept them in all their humanness. That means accepting their weaknesses, accepting their confusions, accepting their absolutely dumbfounding courage, and accepting their dignity and their integrity as individuals, their worth as individuals. This means learning some very, very hard lessons about humility, charity, and love.

And the last, and surprisingly most difficult stage is learning to know and accept yourself in all your own humanness. This means not kidding yourself with fantasies and flattering images manufactured on Madison Avenue. This means recognizing your own worth, being kind to yourself as well as being realistic about your shortcomings. As you struggle through this stage you get to know that the world is tainted, and that things change and wither and die, but you also know a kind of glory in this, the best kind of glory that man is capable of. It comes in that fight to make the good and the true and the beautiful prevail, and you know if you're man enough to make that kind of fight you can use words like that without embarrassment. It's all right to say good, and true and beautiful.

And this is how the world looks a little later on.

The point of that ending is that where there is the challenge of evil and terror there is the excitement and possibility of beauty and good. What can the liberal arts do for this yearning to live in hopes of a fearful glimmer of joy like a spoor and yearning to live with yourself? A knowledge of the world and man is exactly the particular concern of the liberal arts. As I said, in the Renaissance days liberal arts were devoted to what man lives for and how he lives. Now elsewhere the word "arts" has changed its meaning, as you well know. But in the old phrase "liberal, arts," it continues to have its old meaning. And as that phrase is used here at Dartmouth, it covers all the things you study as an undergraduate: all of the fine arts - music, painting, and literature and their histories; all of the humanities; and all the sciences and social sciences as well. And here we need to get clear a very important point about your liberal education at Dartmouth. It's perfectly true that a lot that you study is going to have immediate usefulness in your professions and would perhaps, by the old definition, come under craft arts. It's likewise true that this usefulness is going to be pointed out to you again and again in courses, but the ultimate purpose, the ultimate purpose of the teaching and the learning and your studying, is not to use but to know what the use is for. There's another way of putting this. You study sciences not so much for their laws and their facts as to come to have an understanding of how we look at reality through science. It's a lot more important to know how a physicist envisions reality than it is to know the 32 nuclear particles.

Take another example. When you study economics, much of what you learn there is going to be very useful in business. But you don't study economics for the sake of that. You study it in order to look at man and his experiences through the eyes of the economist. There are many aspects in man's behavior that are best understood from the perspective of the economist, and it's the perspective you re after. To understand how he sees man. Now such is the prestige of physics and economics that nobody in America these days has to insist upon this point very much. But it's a lot more difficult in America, at least today, to convince man that the fine arts offer an indispensa- ble mode of looking at man and human experience. Yet, Dartmouth stands for this and this is why you are sitting in this magnificent building right now. That is why the building was put in such a central place on the campus. I don't want to make this sound too grim and solemn. The fine arts in addition to giving us insights into human experience also give us a unique pleasure, a pleasure which is one of the legitimate goals of living. It is one of the things we want to know about because it is one of the things we live for.

WHAT GIVES us this pleasure? Let's take that up first. Well, sometimes it's just the vivid details. I like, for instance, some of the details in that poem "Dragon Country." However I felt about the whole poem, I still like those details. Then, there is the harmony of the elements. Out in the Jaffe-Friede Gallery is an extraordinary painting, one of the greatest paintings you'll have a chance to see while you are at Dartmouth, and I hope all of you will take a long hard look at it. It's by Jack Levine and is called "Reconstruction." Quite apart from the implicit story material, and quite apart from the implicit character-study in this painting, there's a wonderful, wonderful satisfaction, a wonderful pleasure to be had from the extraordinary harmony of the colors in that picture. If you have any sensitivity to color at all, you're bound to like the way those colors are melted together, and how certain ones stand out - just come roaring off the canvas at you, they're so hot and bright. And they turn out, when you understand the picture, to be very relevant to what the picture is trying to tell you. But it's many things. It's a matter of proportion, getting things right, and balance, interplay of lines. Learning to appreciate these things takes time. It's going to take time to learn all the good things in that Levine painting, and at this point I'd like to make a recommendation to you. When you go to a gallery, if you have time to see all the pictures in an exhibition, fine. But with only a little time you'd be much better off to pick out one picture and spend it all on that one picture. So, if you haven't time to see all the pictures in the Jaffe-Friede Gallery, pick out one, it doesn't necessarily have to be the Levine, but pick out one and really immerse yourself in it. You know, it takes quite a bit of time to do anything well. Nothing worth doing can be done in a hurry from studying a painting to making love. So take time, contemplate, give yourself some leisure.

Arts represent and interpret. In the final work of art when it comes through there's going to be a lot of omission. Things have to be left out to complete the work of art. There's going to be a lot of distortion to get the harmonious balance I spoke of. There's going to be emphasis as the result of these things. A good example occurs in yet another picture on display in the gallery right now. It's by Charles Birchfield and it's called "Song of the Telegraph Wires." It's a very odd picture, very odd indeed, with a minimum of colors. It shows a road leading off to the horizon. Far in the distance is a house by the road on the edge of the horizon and near at hand is some sort of strange building that may be a barn although it may not even be a building at all. It may be a figuration of trees. You're not quite sure. Marching down the road on the right side are the telegraph poles with their wires pushed out of straight line by the wind. The wind is blowing very hard from the right of the picture across to the left. It is blowing the birds, the swallows, the bluebirds. It is blowing the clouds into shapes that make them very much like the shape of flying birds, as if there were great monstrous birds overhead and little birds in the foreground. Much has been left out. The grass and the stones have been left out. The shapes of the telephone poles have been distorted to give you the sense of tremendous pressure from the wind. The houses have been all twisted, and there's this mysterious building. The telegraph wires have been broken up into little pieces as it were to suggest the shattering effect of the wind. And then there's one other detail that you don't see right away, but you do see it after awhile. It's the result of the color contrast. There in the foreground, sitting on a bit of fence wire, looking into the wind, not blown away, in fact sitting there very calmly in unruffled serenity, is a bluebird. That little bit of blue stands out against all these dull grays and browns with extraordinary contrast. All the lines seem at first to focus down the road, but as you look at them longer and longer you see they focus on this little bird. Once you've seen that little bird it holds the whole picture together. From that point on you always look at the bird first, and you keep coming back to it and coming back to it. Now, what does this mean? What does this reveal? When all these irrelevancies have been pruned away, when all the organizations have been used to give clarity and a comprehensiveness that life itself doesn't have, something gets across we can't see in ordinary things which we have to use and, can't just contemplate. Here, all fears that are gendered by loneliness, by a cool windy day, by clouds and sound, are brought through, but what's even more emphatically brought through is the joy symbolized by this bird. It's contrary sound - if it's singing at all, it's singing against the wind and against the sound made by the wind howling through the telegraph wires. The title of the picture is very oblique and indirect. It says "Song of the Telegraph Wires," but the real song is the bluebird's song. This is what art does to you. It brings out qualities in a situation that you are not likely to see by yourself. After you see them they are yours, and henceforth you have a better understanding of that kind of experience in life.

As a result of education in the fine arts and all the liberal arts, you have the right start on this search that I spoke of. A search for your full identity as a person. You are going to be given the kinds of awareness, the kinds of understanding of the varieties of the vision that you need, the vision of the economist, the vision of the physicist, the scientist, the psychologist, the professor of literature, the artist, and all the rest. It is not going to be an easy life, this one that you have started on in a real world. That is, it is not going to be easy if you take the full risks, the full burdens of a human being, but it is going to be full of joy and full of companionship and dignity. And there is a chance of something miraculous happening. At the onset of this, I talked about the shock of reality and the destruction of childhood innocence and childhood irresponsibility and childhood bliss, and I described the way in which men tried to retain the conditions of childhood, the ways in which they try to flee from reality into fantasy, fooling themselves that they can recover the Garden of Eden. It is lost. I have described adult life as full of struggle, that the real world is there, the problem of coming to terms with yourself. I have spoken of how knowledge is needed, and learning here the knowledge that can point you in the right direction. But, you know, the end of the journey may be a return to the lost homestead. Not as a child, but as a man. As one who knows that the world is full of change, knows that there is lurking a disaster, but knows, too, that man is allowed a lot of good things, a lot of the good things he dreamed of far back in that childhood. It is not just Bushwhackers and the men that hung them riding out of the air. And from boyhood some of us carry over some memories of joy, some moments of promise and beauty that haunt us. And you can earn out of your manhood, if you are fully a man, the possibility of recovering these things. And so, after reading to you about how real the world is and about the "Dragon Country" that we all live in, I would like to read one last poem by Robert Penn Warren which tells about the possibility of returning to the beauty that one remembers from childhood. It is called "Gold Blaze" and it is based upon a true experience.

Prof. John Stewart (r) and Prof. JohnFinch (I) with English novelist AnthonyPowell during the writer's 1962 visit.

(Here Prof. Stewart read Kenneth Fearing's "American Rhapsody" showing evenone so trapped in the meaningless rubble ofa life without purpose from which he canescape only by the fantasies encouraged byinferior movies, TV, and advertising hasmoments of doubt and twinges of longingfor self-fulfillment.)

(Here Prof. Stewart read Robert PennWarren's "Dragon Country" where thestruggle against evil and the burden of existence for those who confront reality [theDragon] without benefit of assuaging fantasies or surrender to those who do theirthinking for them has a kind of glory in it.If the Dragon were taken away they woulddecline into ordinariness and miss it.)

". . . a chance of somethingmiraculous happening."

(Here Prof. Stewart described examples ofcultural enjoyment and reward, mentioningmany opportunities available in the HopkinsCenter and on campus. He also describedhow creativity and the arts were "sustainedenemies of repose in man or a society.")

THE AUTHOR: John L. Stewart, Associate Director of the Hopkins Center and Professor of English, is a man well qualified to speak on the liberal arts. He was described for the freshmen in Dean of Freshmen Albert I. Dickerson's introduction as a "Renaissance man." Professor Stewart is a specialist in contemporary British and American literature and aesthetics, is a musician (both oboe and piano) who has played in both the Florida West Coast Symphony and the Dartmouth Community Symphony, and has tried his hand at painting. For the past year Professor Stewart has been on a Dartmouth Faculty Fellowship to study a group of modern poets called "The Fugitives." A book based on the study, The Burden of Time, is nearing completion. His previous books are John Crowe Ransom, Exposition for Science andTechnical Students, and The Essay: A Critical Anthology. A graduate of Denison University with master's and doctorate degrees from Ohio State University, Professor Stewart was director of the General Reading Program from the time it was inaugurated in 1958 until 1962.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

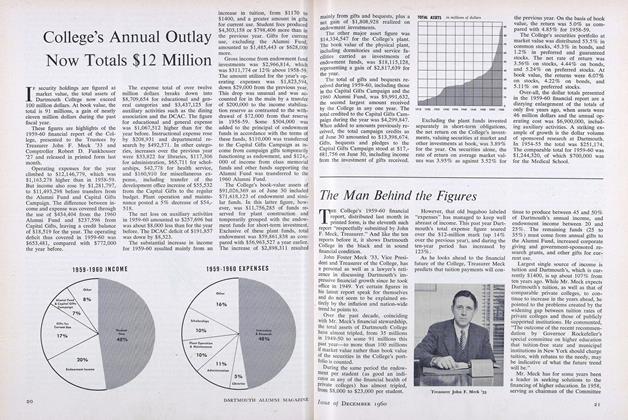

FeatureDARTMOUTH ALUMNI FUND REPORT

November 1963 By Charles F. Moore, Jr. '25 -

Feature

FeatureA TASTE FOR CHANGE

November 1963 -

Feature

Feature"Turn Our Penitence Into Dedication"

November 1963 By Reverend Richard P. Unsworth. -

Feature

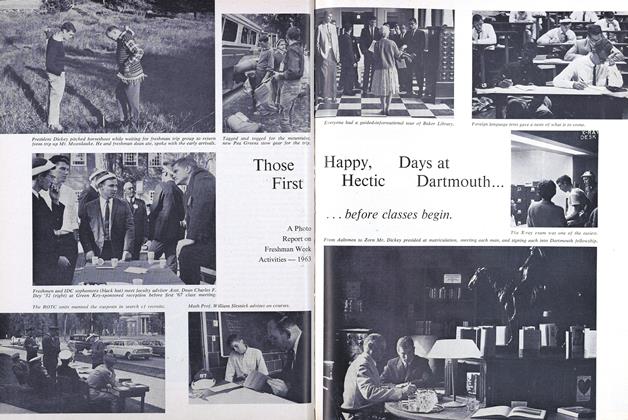

FeatureThose First Happy, Day at Hectic Dartmount

November 1963 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

November 1963 -

Article

ArticleHANOVER CHARACTERS — 1963

November 1963 By ALLEN R. FOLEY '20

Features

-

Feature

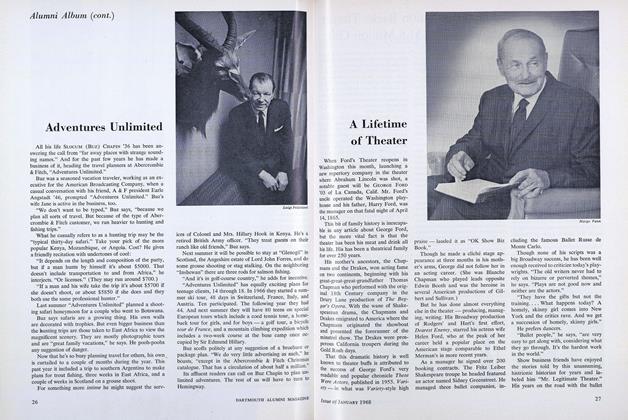

FeatureThe Man Behind the Figures

December 1960 -

Feature

FeatureA Lifetime of Theater

JANUARY 1968 -

Feature

FeatureA PORTFOLIO OF THE Dartmouth Cemetery

November 1973 By ADRIAN BOUCHARD -

Feature

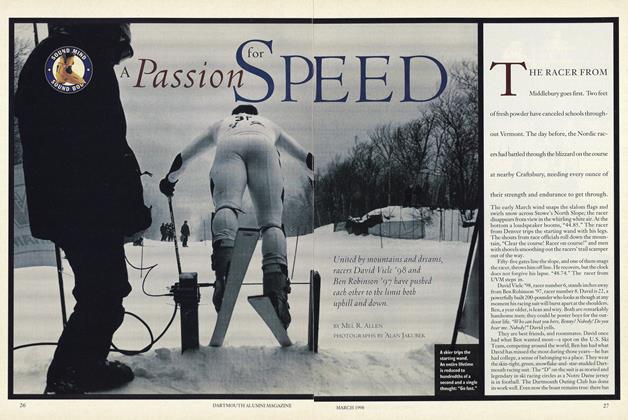

FeatureA Passion for Speed

March 1998 By Mel R. Allen -

Feature

FeatureValedictory to 1957

July 1957 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY -

Cover Story

Cover StoryFather In Law

Nov/Dec 2000 By SARAH JACKSON-HAN ’88