PresidentDickey'sConvocationAddress

Gentlemen of the College and Colleagues:

WE GATHER for this September Convocation in the afterglow of a historic Dartmouth year. 1962-63 has been one of those years whose mark will endure in the life of this institution because it was a year great with fulfillment.

It began in the summer of '62 with a $1,000,000 grant from the Sloan Foundation for graduate engineering in the Thayer School and it closed last month with Dartmouth's first regular fourth term and the most wonderful summer of music, theatre, and the fine arts this North Country has yet known. In between were such other headlines as a second in the nation for the mathematics team; $675,000 from the Ford Foundation for a program of comparative studies in the humanities and social sciences; championships in football, skiing, debating and baseball; the Nathaniel Leverone Field House with its demonstrated potential for multiple use; the fulfilled promise of the Hopkins Center for both College and community; a record Alumni Fund with recognition to match in the Grand Award of the American Alumni Council for sustained alumni support; the largest peacetime graduating class, nearly 700 strong, 80 per cent of whom plan advanced study; all this and a Commencement address which by any standard was historic for both nation and College.

The 1963 Commencement audience which gathered under the tension of lowering clouds - both literally and figuratively - was reminded by the Reverend James Robinson that it was "indeed tragic that in this Centennial year of the Proclamation of Emancipation, America should face its gravest racial crisis." A spontaneous standing ovation climaxed his call for a "second emancipation" which, as he put it, "must be an act of conscience, voluntarily on the part of individual citizens ... to make the race problem their problem and the nation's problem, not just the Negroes problem.

I speak of this today not merely to acknowledge the historic quality of Dartmouth's 1963 Commencement, not merely as an act of personal and official conscience, not merely because the problem presses on our national life with an urgency that now requires "all deliberate speed" be measured in hours and days rather than years and generations; all of these are on my mind, but the over-riding reason for speaking of this matter on this occasion is that it is immensely relevant to the annual joint venture of higher education on which we today embark in this College's one hundred and ninety-fifth year.

THERE is little new to say to each other concerning the relevance of this problem to America's international position. Presidents, Vice Presidents and Secretaries of State from both parties have told us for a decade or more that it is the weakest point in our case before the world's court of last resort - the opinion of free men everywhere. Some of us are actually getting a little peevish on this side of the matter simply because our vociferously self-righteous critics come into that same court with anything but "clean hands." The picture of Khrushchev, Mao, Castro and the like sitting up late worrying at the bedside of anyone's civil rights is unspeakably funny, except, of course, in communist lands where it is simply unspeakable. And it is not merely the communists who find themselves pointing in the mirror when they accuse America of imperfection in extending to all the basic human rights of equal justice and equal opportunity. In truth, there are pitifully few societies, if indeed there are any, where these human rights are not denied to some minority either in fact or law or both. To put it strongly but fairly, America is the prime target of such criticism precisely because today she dares set her course by these stars and must be judged accordingly.

I mention this criticism of us and our shortness with it partly because the best cure I know for peevishness is self-discovery of it, but more importantly because I question whether we realize how effective this particular kind of criticism may be in promoting the spread of meaningful civil rights throughout the international community. Such ideals are not easily transmitted from one nation to another by persuasion, but nations like people can get hoisted with the petard of their criticism of others. I am not counselling more imperfection on our part just to encourage our critics to dig themselves in more deeply, but let's not forget that we as a nation have a long history, which by no means has run its course, of learning many virtues from our critical awareness of their absence in others. Others in turn surely cannot avoid doing the same and this is good, for thus, almost in spite of itself, our world gets educated.

DARTMOUTH itself as an institution has had a long experience with self-education in these matters. As early as 1824 the admission of a Negro into the College was first raised and denied only to be granted on petition of the undergraduates. Since that day there happily has been no such issue here, but it need hardly be said that problems of race were not thereby exorcised from the life of the institution.

One hundred years ago this July, in the middle of the Civil War, a motion before the Dartmouth trustees to grant an important honorary degree was lost by a tie vote, President Lord having voted in the negative from the chair. Thereby Abraham Lincoln failed entry into the Dartmouth fellowship and days later the College lost the service of a preacher-president who became a. victim of his conviction that the Bible ordained slavery.

We are increasingly mindful that one hundred years is too long for disadvantaged American citizens to wait for equal opportunity, but as we face the awesome task of repairing this national neglect it may help keep us in these parts from self-righteousness to remember that it was only a hundred years ago in Hanover, New Hampshire, that as fine a man as Nathan Lord could uphold slavery as a matter of principle.

Although a hundred years happily stands between us as a nation and the issue of slavery it is all to clear today that this has been a period of dangerously postponed progress in bringing the Negro to full citizenship and fair opportunity. In communities such as this it is not so much that bad things were done as that good things were not. It is sobering enough just to recall that it is only three years since this citadel of higher education freed itself of fraternity charters which taught Dartmouth men to practice racial discrimination in passing on the merits of their fellows as social companions. On the brighter side it is due the pioneering courage of the generation of Dartmouth undergraduates who gained this latest emancipation for this campus to remember that theirs was an achievement in self-education and self-liberation of which we are the beneficiaries. This community is today a little more committed to the ideals and work of education because of what those Dartmouth men learned and did here just yesterday.

SEVERAL years ago a Negro student called on me toward the end of his senior year. He came to say a word of thanks for his experience at Dartmouth - something that is not conspicuously common. He was a mature, poised person who had found his deepest satisfaction here just in "passing current" as an individual, with neither discount nor premium attaching to his color. Yes, he said, there had been a few difficult times but on the whole he had only one regret about his Dartmouth years - "they may have been too good; I wonder whether I am prepared for going back to what is now ahead." Such a man makes a full and fair return to the education of all of us and Dartmouth will be the better for it when more like him find their way as individuals into the welcome that is here as students, staff and faculty. I need hardly add that America will be the better for it when no man need dread "going back to what is now ahead." I will add that in this as in all else it must be our constant concern in the days ahead to see both College and Nation well served.

And, gentlemen, racial relations is only one of the fronts of change. Ours is a time when accelerating change, not merely change, is the law of life. In such a time every step forward is little enough, often even before it is completed. It has been said on this occasion before that "change is opportunity," but I say to you only for those who are prepared for it. For the unprepared it can be all kinds of misery. This truth is taught by the history of every subject studied in this College. It is why businessmen fear obsolescence as their forefathers feared the plague; it is also why when obsolescence gets into an enterprise, be it business or government, all too often the remedy prescribed is that ancient, major surgical procedure known as the rolling of heads.

BEING prepared for change has always been one of the functions of education; it is the prime function of an enterprise which presumes to prepare men for leadership in a time of accelerating change. A leader in any walk of life in the American community today must not only be able to stand change, he must have a taste for it; he must be able to judge it, spotting the specious, but also knowing that there are seasons of need other than his own in which change ripens. And if any leadership is to be creative as well as good, it must on occasion generate the change it leads. Finally, the prerequisite to all these is a capacity for being undismayed when, as happens to all of us, we come face to face with change we neither made nor foresaw and "damn well don't like." Indeed, if I were to select just one quality necessary today to a lifetime of self-liberation I think it would probably be the capacity for being undismayed. The "impossibilities," the "unreasonable" changes, the imperfections of the other fellow, which confound us at the moment are going to increase in a way that few of us can stand to think about. And yet that is just what we must be able to do - "stand to think.' To update Kipling a little, if you learn to live as both a creature and a creator of change, and if you can acquire the self-discipline of the undismayed, you just may be more than a match for a future which although not entirely June-like, is surely "bustin' out all over."

I should add that as always my generation stands in more urgent need of these things than does this contemporary college generation. In truth, one hesitates to speak to youth of these things just because nothing has seemed more natural, right and feasible to most younger generations than change; and as for your ever being dismayed, few of us (except perhaps the Dean) ever see it. In this, as in so much else that is wonderful at Dartmouth, we older ones can say with Robert Frost, Class of 1896, "I go to school to youth to learn the future." Some day later you will find yourself in the midst of the future about which you taught us and hopefully, still having a taste for that future, you will say with the same poet, "I never dared be radical when young for fear it would make me conservative when old."

These words will remind many of you, as they do me, that along with the good things, 1963 was also for us at Dartmouth sadly historic with change. Today we open the first college year in a long time when the men of Dartmouth will not have Robert Frost with them. It is fitting to tell you that his last words to me just days before his death were about you. "Tell them you saw me," he said. And I do.

And this brings us, men of Dartmouth, to what I have said on this occasion before. As members of the College you have three different but closely intertwined roles to play:

First, you are citizens of a community and are expected to act as such. Second, you are the stuff of an institution and what you are it will be. Thirdly, your business here is learning and that is up to you. We'll be with you all the way, and Good Luck!

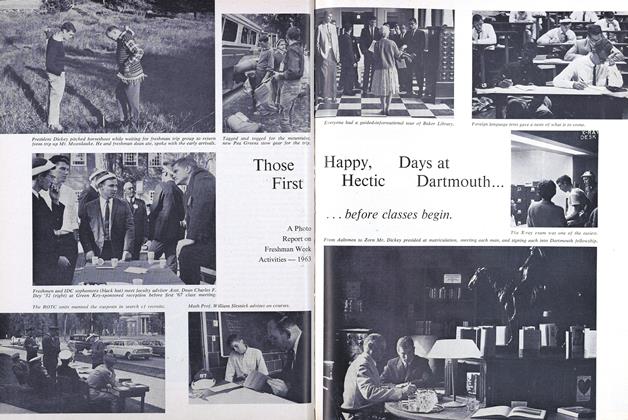

Dean of Freshmen Albert I. Dickerson '30 (I), President Dickey, Dean of the Tucker Foundation Richard Unsworth, and Dean ofthe College Thaddeus Seymour (r) are on the podium as faculty members march in for September 23rd Convocation ceremony.

The President (r) and Prof. William Smith, chairman of thePsychology Department, at the post-Convocation coffee.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDARTMOUTH ALUMNI FUND REPORT

November 1963 By Charles F. Moore, Jr. '25 -

Feature

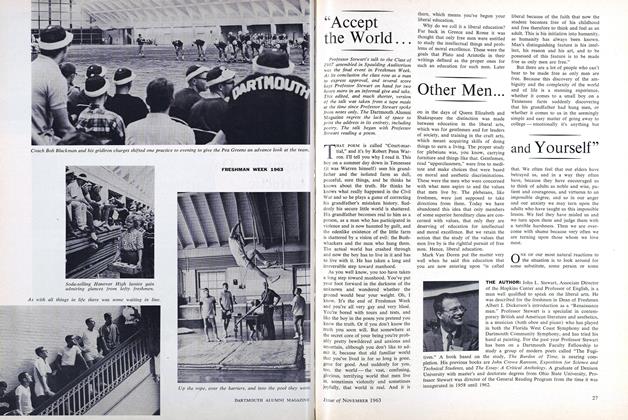

Feature"Accept the World..., Other Men...and Yourself"

November 1963 -

Feature

Feature"Turn Our Penitence Into Dedication"

November 1963 By Reverend Richard P. Unsworth. -

Feature

FeatureThose First Happy, Day at Hectic Dartmount

November 1963 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

November 1963 -

Article

ArticleHANOVER CHARACTERS — 1963

November 1963 By ALLEN R. FOLEY '20

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Class Officers Weekend

JUNE 1970 -

Feature

FeatureWhitman at Dartmouth—100 Years Ago

JUNE 1972 -

Feature

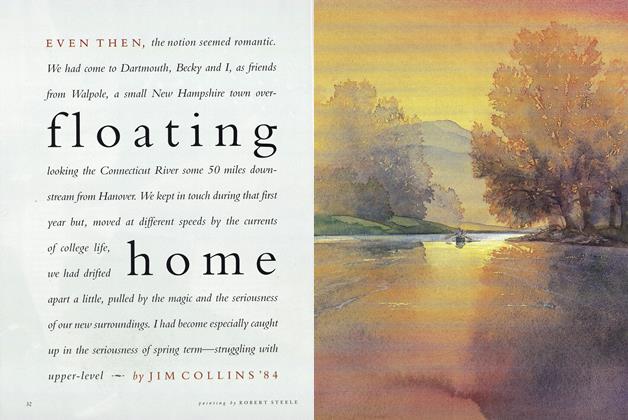

FeatureFloating Home

June 1992 By Jim Collins '84 -

Feature

FeatureEgyptologist

DECEMBER 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

Feature"Dartmouth Visited"

October 1956 By ROBERT L. ALLEN '45 -

Feature

FeatureNow Let Him Praise Emmets

November 1980 By Robert Sullivan