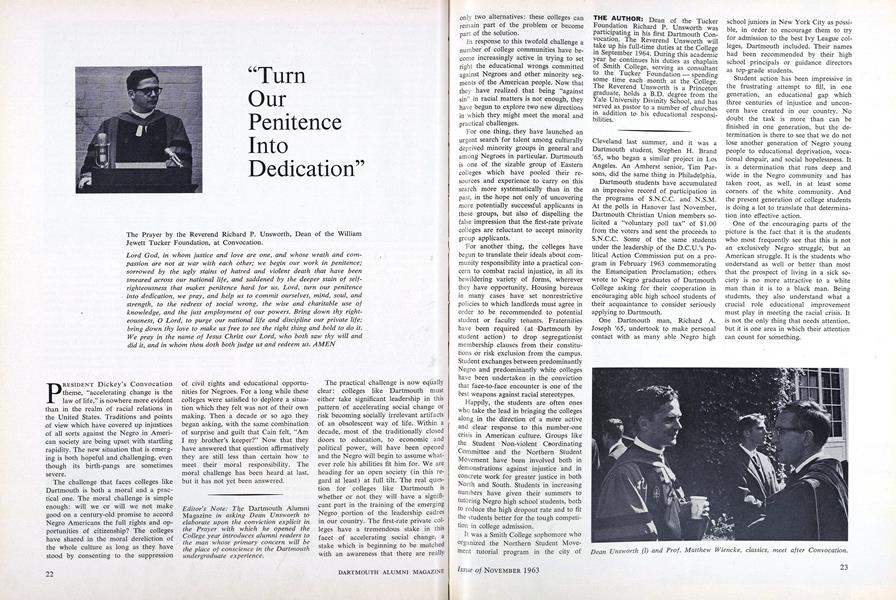

Dean of the William Jewett Tucker Foundation, at Convocation.

Lord God, in whom justice and love are one, and whose wrath and compassion are not at war with each other; we begin our work in penitence;sorrowed by the ugly stains of hatred and violent death that have beensmeared across our national life, and saddened by the deeper stain of self-righteousness that makes penitence hard for us. Lord, turn our penitenceinto dedication, we pray, and help us to commit ourselves, mind, soul, andstrength, to the redress of social wrong, the wise and charitable use ofknowledge, and the just employment of our powers. Bring down thy righteousness, O Lord, to purge our national life and discipline our private life;bring down thy love to make us free to see the right thing and bold to do it.We pray in the name of Jesus Christ our Lord, who both saw thy will anddid it, and in whom thou doth both judge us and redeem us. AMEN

PRESIDENT Dickey's Convocation theme, "accelerating change is the law of life," is nowhere more evident than in the realm of racial relations in the United States. Traditions and points of view which have covered up injustices of all sorts against the Negro in American society are being upset with startling rapidity. The new situation that is emerging is both hopeful and challenging, even though its birth-pangs are sometimes severe.

The challenge that faces colleges like Dartmouth is both a moral and a practical one. The moral challenge is simple enough: will we or will we not make good on a century-old promise to accord Negro Americans the full rights and opportunities of citizenship? The colleges have shared in the moral dereliction of the whole culture as long as they have stood by consenting to the suppression of civil rights and educational opportunities for Negroes. For a long while these colleges were satisfied to deplore a situation which they felt was not of their own making. Then a decade or so ago they began asking, with the same combination of surprise and guilt that Cain felt, "Am I my brother's keeper?" Now that they have answered that question affirmatively they are still less than certain how to meet their moral responsibility. The moral challenge has been heard at last, but it has not yet been answered.

The practical challenge is now equally clear: colleges like Dartmouth must either take significant leadership in this pattern of accelerating social change or risk becoming socially irrelevant artifacts of an obsolescent way of life. Within a decade, most of the traditionally closed doors to education, to economic and political power, will have been opened and the Negro will begin to assume whatever role his abilities fit him for. We are heading for an open society (in this regard at least) at full tilt. The real question for colleges like Dartmouth is whether or not they will have a significant part in the training of the emerging Negro portion of the leadership cadres in our country. The first-rate private colleges have a tremendous stake in this facet of accelerating social change, a stake which is beginning to be matched with an awareness that there are really only two alternatives: these colleges can remain part of the problem or become part of the solution.

In response to this twofold challenge a number of college communities have become increasingly active in trying to set right the educational wrongs committed against Negroes and other minority segments of the American people. Now that they have realized that being "against sin" in racial matters is not enough, they have begun to explore two new directions in which they might meet the moral and practical challenges.

For one thing, they have launched an urgent search for talent among culturally deprived minority groups in general and among Negroes in particular. Dartmouth is one of the sizable group of Eastern colleges which have pooled their resources and experience to carry on this search more systematically than in the past, in the hope not only of uncovering more potentially successful applicants in these groups, but also of dispelling the false impression that the first-rate private colleges are reluctant to accept minority group applicants.

For another thing, the colleges have begun to translate their ideals about community responsibility into a practical concern to combat racial injustice, in all its bewildering variety of forms, wherever they have opportunity. Housing bureaus in many cases have set nonrestrictive policies to which landlords must agree in order to be recommended to potential student or faculty tenants. Fraternities have been required (at Dartmouth by student action) to drop segregationist membership clauses from their constitutions or risk exclusion from the campus. Student exchanges between predominantly Negro and predominantly white colleges have been undertaken in the conviction that face-to-face encounter is one of the best weapons against racial stereotypes.

Happily, the students are often ones who take the lead in bringing the colleges along in the direction of a more active and clear response to this number-one crisis in American culture. Groups like the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee and the Northern Student Movement have been involved both in demonstrations against injustice and in concrete work for greater justice in both North and South. Students in increasing numbers have given their summers to tutoring Negro high school students, both to reduce the high dropout rate and to fit the students better for the tough competition in college admission.

It was a Smith College sophomore who organized the Northern Student Movement tutorial program in the city of Cleveland last summer, and it was a Dartmouth student, Stephen H. Brand 65, who began a similar project in Los Angeles. An Amherst senior, Tim Parsons, did the same thing in Philadelphia.

Dartmouth students have accumulated an impressive record of participation in the programs of S.N.C.C. and N.S.M. At the polls in Hanover last November, Dartmouth Christian Union members solicited a "voluntary poll tax" of $1.00 from the voters and sent the proceeds to S.N.C.C. Some of the same students under the leadership of the D.C.U.'s Political Action Commission put on a program in February 1963 commemorating the Emancipation Proclamation; others wrote to Negro graduates of Dartmouth College asking for their cooperation in encouraging able high school students of their acquaintance to consider seriously applying to Dartmouth.

One Dartmouth man, Richard A. Joseph '65, undertook to make personal contact with as many able Negro high school juniors in New York City as possible, in order to encourage them to try for admission to the best Ivy League colleges, Dartmouth included. Their names had been recommended by their high school principals or guidance directors as top-grade students.

Student action has been impressive in the frustrating attempt to fill, in one generation, an educational gap which three centuries of injustice and unconcern have created in our country. No doubt the task is more than can be finished in one generation, but the determination is there to see that we do not lose another generation of Negro young people to educational deprivation, vocational despair, and social hopelessness. It is a determination that runs deep and wide in the Negro community and has taken root, as well, in at least some corners of the white community. And the present generation of college students is doing a lot to translate that determination into effective action.

One of the encouraging parts of the picture is the fact that it is the students who most frequently see that this is not an exclusively Negro struggle, but an American struggle. It is the students who understand as well or better than most that the prospect of living in a sick society is no more attractive to a white man than it is to a black man. Being students, they also understand what a crucial role educational improvement must play in meeting the racial crisis. It is not the only thing that needs attention, but it is one area in which their attention can count for something.

Dean Unsworth (I) and Prof. Matthew Wiencke, classics, meet after Convocation.

Editor's Note: The Dartmouth Alumni Magazine in asking Dean Unsworth toelaborate upon the conviction explicit inthe Prayer with which he opened theCollege year introduces alumni readers tothe man whose primary concern will bethe place of conscience in the Dartmouthundergraduate experience.

THE AUTHOR: Dean of the Tucker Foundation Richard P. Unsworth was participating in his first Dartmouth Convocation. The Reverend Unsworth will take up his full-time duties at the College m September 1964. During this academic year he continues his duties as chaplain of Smith College, serving as consultant to the Tucker Foundation - spending some time each month at the College. The Reverend Unsworth is a Princeton graduate, holds a B.D. degree from the Yale University Divinity School, and has served as pastor to a number of churches in addition to his educational responsibilities.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDARTMOUTH ALUMNI FUND REPORT

November 1963 By Charles F. Moore, Jr. '25 -

Feature

Feature"Accept the World..., Other Men...and Yourself"

November 1963 -

Feature

FeatureA TASTE FOR CHANGE

November 1963 -

Feature

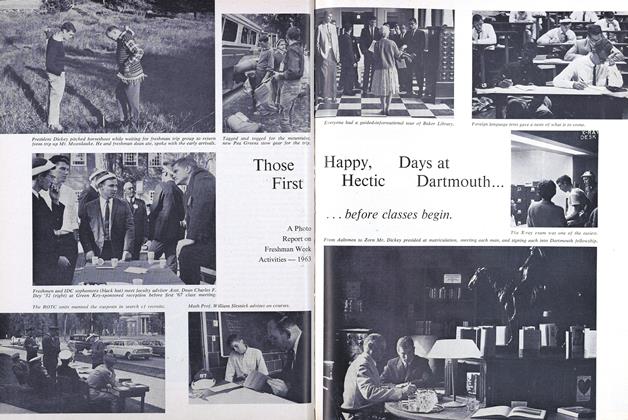

FeatureThose First Happy, Day at Hectic Dartmount

November 1963 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

November 1963 -

Article

ArticleHANOVER CHARACTERS — 1963

November 1963 By ALLEN R. FOLEY '20

Features

-

Feature

FeatureTrustees Meet with Alumni Council

FEBRUARY 1968 -

Cover Story

Cover Story"GALLANT SERVICE"

May/June 2013 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryPiece of the Action: The Stanfa Hit

OCTOBER 1994 By George Anastasia -

Feature

FeatureNine-Man Council Charts Course for Development

January 1954 By GEORGE H. COLTON '35 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCAN WE TALK?

MAY 1989 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureCAN CONGRESS SURVIVE?

JANUARY 1965 By ROGER H. DAVIDSON