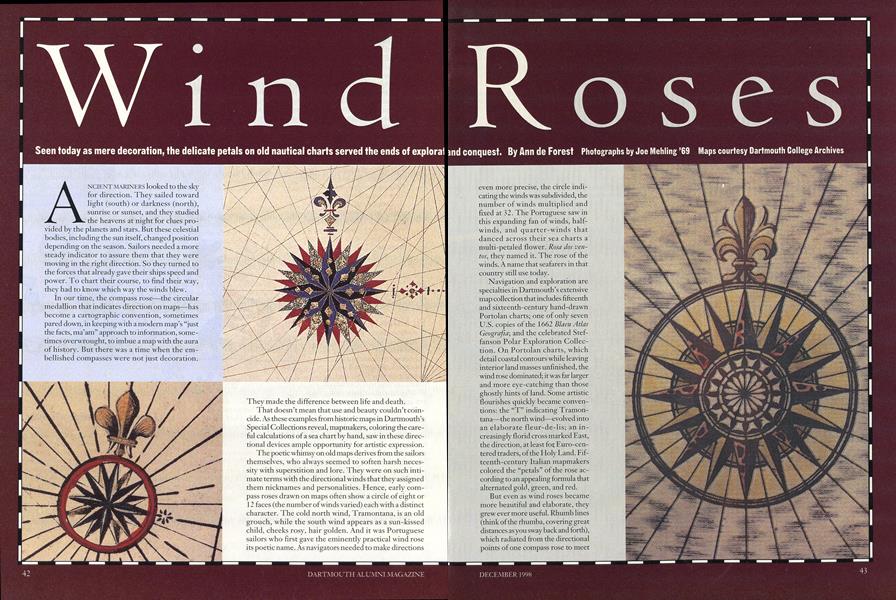

Seen today as mere decoration, the delicate petals on old mautical charts served the ends of explorat and conquest

ANCIENT MARINERS looked to the sky for direction. They sailed toward light (south) or darkness (north), sunrise or sunset, and they studied the heavens at night for clues provided by the planets and stars. But these celestial bodies, including the sun itself, changed position depending on the season. Sailors needed a more steady indicator to assure them that they were moving in the right direction. So they turned to the forces that already gave their ships speed and power. To chart their course, to find their way, they had to know which way the winds blew.

In our time, the compass rose—the circular medallion that indicates direction on maps—has become a cartographic convention, sometimes pared down, in keeping with a modern map's "just the facts, ma'am" approach to information, sometimes overwrought, to imbue a map with the aura of history. But there was a time when the embellished compasses were not just decoration. They made the difference between life and death.

That doesn't mean that use and beauty couldn't coincide. As these examples from historic maps in Dartmouth's Special Collections reveal, mapmakers, coloring the careful calculations of a sea chart by hand, saw in these directional devices ample opportunity for artistic expression.

The poetic whimsy on old maps derives from the sailors themselves, who always seemed to soften harsh necessity with superstition and lore. They were on such intimate terms with the directional winds that they assigned them nicknames and personalities. Hence, early compass roses drawn on maps often show a circle of eight or 12 faces (the number of winds varied) each with a distinct character. The cold north wind, Tramontana, is an old grouch, while the south wind appears as a sun-kissed child, cheeks rosy, hair golden. And it was Portuguese sailors who first gave the eminently practical wind rose its poetic name. As navigators needed to make directions even more precise, the circle indicating the winds was subdivided, the number of winds multiplied and fixed at 32. The Portuguese saw in this expanding fan of winds, half-winds and quarter-winds that danced across their sea charts a multi-petaled flower. Rosa dos ventos, they named it. The rose of the winds. A name that seafarers in that country still use today.

Navigation and exploration are specialties in Dartmouth's extensive map collection that includes fifteenth and sixteenth-century hand-drawn Portolan charts; one of only seven U.S. copies of the 1662 Blaeu Atlas Geografia; and the celebrated Steffanson Polar Exploration Collection. On portolan charts, which detail coastal contours while leaving interior land masses unfinished, the wind rose dominated; it was far larger and more eye-catching than those ghostly hints of land. Some artistic flourishes quickly became conventions: the "T" indicating Tramontana-the north wind—evolved into an elaborate fleur-de-lis; an increasingly florid cross marked East, the direction, at least for Euro-centered traders, of the Holy Land. Fif-teenth-century Italian mapmakers colored the "petals" of the rose according to an appealing formula that alternated gold, green, and red.

But even as wind roses became more beautiful and elaborate, they grew ever more useful. Rhumb lines (think of the rhumba covering great distances as you sway back and forth), which radiated from the directional points of one compass rose to meet the points of another, became the highways of the ocean. Navigators might not be able to build roads on the open sea, but they could establish reliable routes based on the currents of wind and water, a method airplane pilots and ships' captains still follow—using much more sophisticated instruments—to chart course today. (Rhumb lines also gave sailors an early indication that the world wasn't as flat as they assumed. Following one line for too long would not lead in a steady, straight direction, but twist you about, turn your straightforward journey into a spiral of confusion.)

Then there was the day, sometime in the thirteenth century, that some savvy sailor thought to combine a wind rose with the ship's latest navigational tool, the magnetic compass.: He cut a wind rose from a map (or drew one himself) stuck it in the compass bowl underneath the magnetized needle (which, as if by magic, pointed north), and gave birth to that indispensable instrument favored by navigators and trailblazers-professional and amateur—the world over. The rosa dos Veritas became more commonly known as the compass rose.

Since we no longer depend on the winds for speed or direction, it is easy to admire wind roses from afar, without fully understanding all they tell us. These lovely "flowers" say much about human history, about our yearnings and aspirations, about our ingenious attempts to explain and contain natural phenomena through geometrica metrical abstraction. For wind roses and rhumb lines do nothing less than tame the winds and the ocean's currents; they tap into natural forces and make them serve the ends of exploration and conquest.

All maps, ancient and contemporary, have stories to tell, equally involving. That's why, for example, Professor Terry Osborne sends freshmen in his "Essays of Place" seminar to Baker Library's map room in the first weeks of class. There students find an entirely different interpretation of Walden Pond or Annie Dillard's Pilgrim at Tinker Creek or Alfred Kazin's Brooklyn. Osborne borne sees maps as just another kind of essay of place, as eloquent and revealing, in their own coded language, as words on a printed page.

Wind roses can be read for advice as well as history. Contained in those multiple petals is some surprisingly sage counsel for modern times. For ancient mariners a wind rose advised both focus and flexibility. If your life sometimes feels as though you're out in the middle of the ocean without even a star to show the way, you might want to pay heed. Set a direction, the wind rose reminds us. Stay the course. And always know which way the winds are blowing.

ANN DE FOREST is a design critic for the New York Times, Philadelphia Inquirer, and National Public Radio. Maproom hours are 8 a.m. to 4:30 p.m., Monday through Friday.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

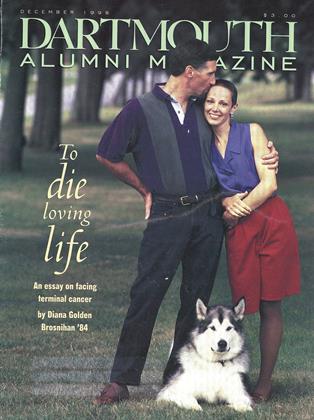

Cover StoryTo die loving life

December 1998 By Diana Golden Brosnihan '84 -

Feature

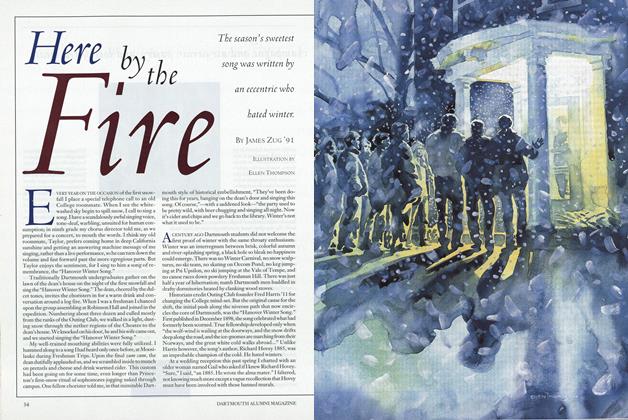

FeatureHere by the Fire

December 1998 By James Zug '91 -

Feature

FeaturePost What?

December 1998 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticlePrediction Fiction

December 1998 By Christine Schultz -

Class Notes

Class Notes1997

December 1998 By Abby Klingbeil -

Article

ArticleLooking for Frost

December 1998 By Noel Perrin

Ann de Forest

Features

-

Feature

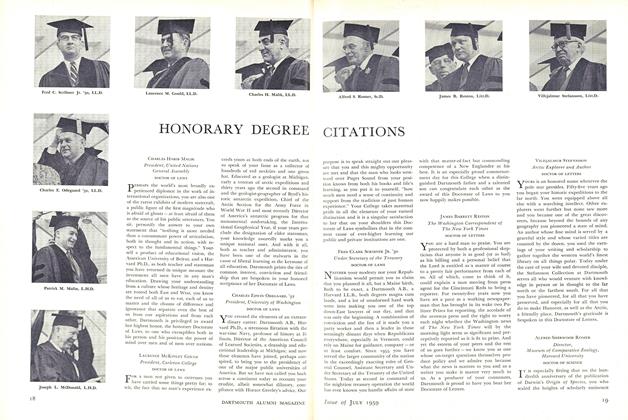

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

JULY 1959 -

Feature

FeatureIn sum:

April 1962 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryFred McFeely Rogers 1950

NOVEMBER 1990 -

Feature

FeatureThe 'real world': Ivies in the cold, cold ground

JAN.- FEB. 1982 By Cliff Jordan -

Feature

FeatureThe Trustees: 15 men and a woman with ultimate authority

October 1979 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureThird Panel Discussion

October 1951 By HANSON W. BALDWIN