TEN years or so after graduation the average college man suffers the Walter Mitty disease - a vague abdominal discomfort accompanied by a chill of recognition: the dreams will still be dreamt but the dreamer will not really write the great American novel, he will never answer the call of "Author, author" on opening night, the Medal of Honor will never be pinned to his chest, he and his wahine will never plunge into the Pacific lagoon by moonlight.

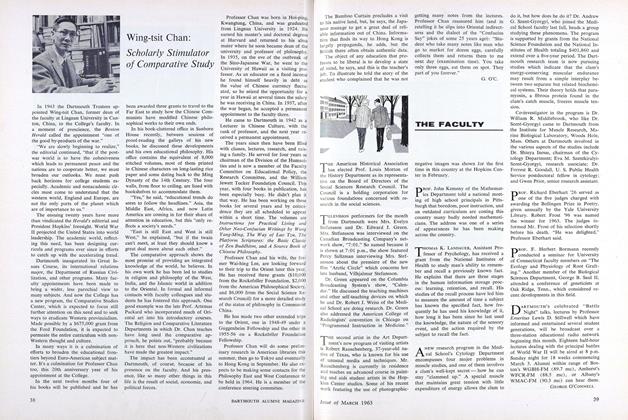

One Dartmouth man, however, has avoided this illness of age. He is Richard M. Watt, Class of 1952. And it is strange he should be the one to escape for he would appear an ideal candidate for a chronic Mitty condition. He is apparently completely trapped in the middle-class, for Watt is a successful salesman, a Republican, an Episcopalian, owner of one mortgage and two cars. He commutes from the suburb of Glen Ridge, New Jersey; he is married and has three children - two daughters and a son. But he has a saving vice - he is a secret author.

He doesn't have to dream of exotic worlds beyond the horizon while he reclines during the businessmen's flight to Chicago, because he lives successfully in two worlds. Somewhat to his own astonishment he is now an author complete with a literary agent and a publisher. He has already signed presentation copies of his book, and he has been invited to speak to a suburban women's club.

To the professional writer, Dick Watt's accomplishments are as extraordinary as if he decided - without ever playing baseball - that he'd like to pitch for the Yankees and ended up taking his regular turn with Whitey Ford. "Only in America," said one novelist with a slightly green smile, "could a flooring materials salesman become a respected historian and an admired writer with the first thing he'd ever written."

That is exactly what Watt has done. Dare Call It Treason, which is reviewed on page 7, received praise from both American and European critics before it was published February 21 by Simon and Schuster. It is a political and military history of the mutinies of the French Army in World War I. It was hailed by Barbara Tuchman, author of The Gunsof August, as "an original and valuable work of history." S. L. A. Marshall, author of Night Drop and The River andthe Gauntlet, said, "Anyone who loves writing for its own sake and is fascinated by the story of men in great adversity will relish this book." English military historian Cyril Falls adds, "I consider Dare Call It Treason a masterpiece." William L. Shirer, author of Rise andFall of the Third Reich, declares it is "fascinating . . . you cannot put it down."

It is hard to find anything in Dick Watt's background which would have predicted his sudden second birth as a serious historian at the age of 32. "I had a happy childhood," he says, obviously surprised at a question about his relationship with his parents. At Glen Ridge High School he was an average student and an average football player. At Dartmouth he never revealed a weakness for the intellectual world. He majored in English but took not a single course in writing and his only study of history was a one-semester freshman course in Modern European History under Professor John C. Adams. His over-all average was a modest 2.2, and he adds, "I worked hard to get it."

He was a sometimes announcer on WDBS, played freshman lacrosse, ran the Dartmouth Community Chest in 1952 (when he rose at a rally and asked for contributions to the Camon Dunyon Runcer Fund), worked a year on TheDartmouth, and was elected vice-president of Sigma Nu in his senior year.

A Naval ROTC student, Watt went to sea ten days after graduation and served for three years on a destroyer in the Atlantic, Caribbean, and Mediterranean. In 1953, while still in the Navy, he married Sandra Fitch (Mt. Holyoke '56), daughter of Charles P. Fitch, Dartmouth '25, and sister of Charles Fitch, Class of '63.

After Dick Watt was discharged as a Lieutenant j.g., he went to work for Crossfield Products Corporation which manufactures marine, industrial, and institutional floor coverings. He became a proper suburbanite and a good Dartmouth alumnus, serving as a member of his class executive committee from 1957 to 1962 and as class newsletter editor for eight years. His life seemed clearly defined and entirely predictable when a red stationwagon with New Hampshire license plates cut ahead of him in a line of cars waiting for the Shelter Island, Long Island ferry in August 1959.

Because the New Hampshire car had books in the back, Dick assumed, with fine parochialism, that the driver must be a Dartmouth professor and he went over to strike up a conversation. He was not a Dartmouth man but Evan Hill, a writer who lives in Newport, New Hampshire. "I did the unpardonable thing," Dick smiles, remembering that day, "but I didn't realize it until people have started doing it to me. I told him I had a good idea that he ought to write up. His face took on a glazed expression but he listened."

Dick Watt's idea was that the untold story of the French army mutinies in World War I ought to be told. He'd first heard of them when he was ten years old and read a Reader's Digest anthology his parents received as a Book-of-the-Month Club dividend. In a casual, purposeless way he read World War I history from then on and began keeping a mental file on the mutinies. To convince Hill there was a mazagine article in the mutinies Watt wrote him a twelve-page, single - spaced letter. Impressed and astonished, Hill answered that maybe Watt ought to write it himself. He added as an aside that he must be the neighbor of a freelance writer friend. Introduced by mail, the writer, Don Murray, read the letter and agreed, "You ought to write it yourself." Over a drink the magazine writer's wife, Minnie Mae Murray, casually added, "Write a book. There's no future in writing magazine articles."

"So I wrote a book," Watt laughs. "She seemed to know what she was talking about, so I did as I was told."

In September 1959 he started reading books on World War I, making notes and keeping what he was doing a secret. He wouldn't even ask librarians for help. "Everybody knows a salesman can't write a book," Watt smiles, "and I wasn't going to tell anyone about it and look ridiculous."

He used the Glen Ridge Library but principally the unequalled research facilities of the New York Public Library. When he discovered many of his sources were in French, Dick bought a paperback French grammar at a bookstore in the Buffalo Airport, cut out the lessons and pasted them on index cards. He proceeded to teach himself to read French (his foreign language in high school and college had been Spanish) in spare moments waiting for planes or customers. "I found out that Dartmouth was right about a liberal arts education," he explains; "it teaches you to learn how to learn."

Watt didn't cut down on any of his activities to write his book and he is a very busy man. Two days a week he goes to the office, arriving before 8:30 in the morning and staying until after 6:30. Three days a week he travels, taking the 7:00 a.m. plane to Cleveland, Pittsburgh, Chicago or Boston, or driving up to Connecticut or New York State. He generally meets customers for breakfast, and frequently entertains others in the evening. He usually spends at least half a day Saturday in the office, teaches Sunday School, and leads an active social life. Last year he took a four-day vacation, the year before that one week, and the year before none at all.

Yet his book began to build up. A few hours in the New York Public Library on a Saturday afternoon, an evening or two of reading, a few Sunday afternoons of writing and a section would start to take shape. He also bought obscure French books through a book-finding service, sought out French World War I veterans in the United States and acquired masses of photostats of French books from U. S. and European libraries.

He went about his writing instinctively, for he has never read a book on How ToWrite. He had always liked to reduce things to a step-by-step outline. When Dick went aboard ship in the Navy he was made gunfire control officer and an enlisted man began, "First you gate the overlap." Ensign Watt quickly answered, "Hold it right there."

Watt explains, "I think we are often the victims of specialists and their private languages. I decided right then to reduce all the steps of the Mark 63 gunfire control system to English, and to number the knobs on the computer controls so I could understand them." Soon his system was adopted by the destroyer division, then by the Atlantic Fleet, and finally by the entire United States Navy. When Dick Watt went to work for Crossfield Products he ran into a similar problem. Everyone in the company knew how to apply their products but no one knew how to tell anyone else how to do it. He wrote the company's first application manual and began a basic sales training course for the distributors which he still runs today.

In 1959 Watt started the same logical attack on French history. He got some 18-entry bookkeeping pages and outlined the book, then he outlined the individual chapters. He took one chapter outline at a time and expanded a four-inch section to a four-page outline. That outline became a rough draft which revealed the holes in his knowledge. Taking on the book a section at a time, he dug up the information he had to know and wrote about fifteen manuscript pages, corrected it, and gave it to his wife to type. "Then I'd discover what I was missing," Watt says. He'd track that information down and rewrite the fifteen pages into a first draft. He was becoming a writer - he'd mark that up and rewrite it, and rewrite that and then rewrite it again.

Today he says, "I realized how important it was to bite off a small chunk at a time. I didn't worry about the whole book, I didn't even worry about an entire chapter. If I had ever let myself realize I had a whole book to write, I never would have written it."

He began, however, to admit to people he was writing a book. Material poured in from France and from the Hoover Library in California; he made frequent use of the West Point Library. In eighteen months he had seven chapters finished.

He submitted this to an agent, Herb Jaffe, who sent it to one publishing house, which was not interested, and then to Simon and Schuster, which offered him a sizable advance. "They took me seriously," Watt says, still with a trace of surprise. "I'd never published anything at all, but suddenly I had an agent and a publisher and an editor. I even had a check." He continued to work, finishing about 2000 words a weekend. In all, Dick Watt estimates that it took him the equivalent of about 100 working days to research and write the book.

Dick's advice to others who want to escape the Walter Mitty disease is simple. "First you have to have a wife who understands," he says. "That sounds corny, but you just couldn't do it if your wife resented the time it takes. Sandy and I had our moments - I should have spent more time with the kids - but she supported me in the work and typed four drafts of the book- about half-a-million words in all - using a borrowed typewriter set up on the dining-room table.

"The other thing that's important is to do it. I'd always wanted to write something, but I hadn't dared. I guess my advice to anyone else is to dare. Start, don't think about it or talk about it, just start writing, and don't stop."

There are other things Watt doesn't mention. He reads fast and he has an extraordinary memory. He has the 180° vision which allows him to scan a century of history and the perception to see what is meaningful. He has energy, enthusiasm, and a sense of the dramatic. Most of all, he has talent: a native ability to use the language with such precision and grace the reader is first trapped, then entertained, and finally educated.

Dick Watt is surprised that writers and editors "treated me as if I were a writer from the beginning." The reason they did is that he was a writer, he had all the instincts of a pro. Michael V. Korda, one of Watt's editors, says energetically, "Richard Watt is not a part-time writer, a dilettante. He is no hobbiest. His is a serious talent, and the authorities in his field consider him a serious historian. Dare Call It Treason is not just a good book, it is clearly the beginning of a major work of history which will be told in a number of volumes. And when that work is finished there will be other important works by Mr. Watt. He is not a flooring materials salesman who writes; he is a writer who happens to be a businessman as well, the way other writers are physicians or professors."

Dick has no intention of giving up his job as a salesman, growing a beard or voting Democratic - he is even a bit hurt that some of his neighbors have begun to suspect he is an intellectual. He has, however, let his subcription to Fortune run out while his subscription to the London Times Literary Supplement has just begun. He has finished 30,000 words of his next book, and the children's second-floor playroom is now a writer's workroom decorated with the books, notes, outlines, and crumpled balls of discarded drafts that are the mark of the professional writer.

Richard Watt may not quite believe it yet but he has been permanently cured of the Walter Mitty disease. When they call "author" they, in fact, call for him.

Richard M. Watt '52

THE AUTHOR: Don Murray, a neighbor and close friend of Dick Watt in Glen Ridge, N.J., has been a professional writer for more than a dozen years. His articles appear regularly in the Reader's Digest and have been printed in the Saturday Evening Post and other magazines. With short stories and a non-fiction juvenile also to his credit, he aims to move on to the novel, and has completed one and is working on another. A native of Boston and a graduate of the University of New Hampshire, Murray rose from copy boy to editorial writer on the Boston Herald and in 1954 won the Pulitzer Prize for editorials on national defense.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeaturePOETRY AT DARTMOUTH

March 1963 By RICHARD EBERHART '26 -

Feature

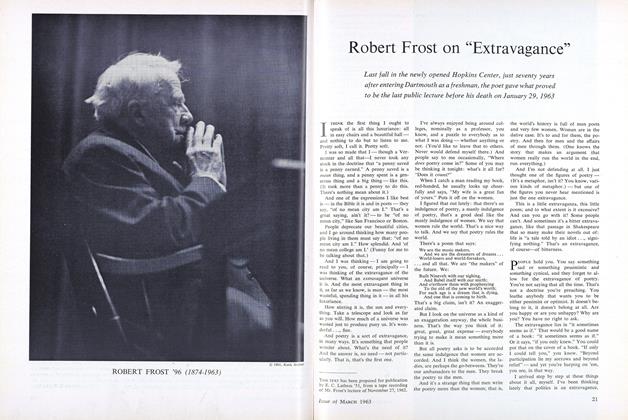

FeatureRobert Frost on "Extravagance"

March 1963 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

March 1963 By JOHN HURD, HUGH M. MCKAY -

Article

ArticleScholarly Stimulator of Comparative Study

March 1963 By G.O'C. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

March 1963 By CHARLES F. MCGOUGHRAN, ALBERT W. FREY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1940

March 1963 By ROBERT W. MACMILLEN, DONALD G. RAINIE

Features

-

Feature

FeatureHOW THE "IVY LEAGUE" GOT ITS NAME

November 1961 -

Cover Story

Cover Story"You'll Know What to Do"

APRIL 1997 By Bruce Duthu '80 -

Feature

FeatureAlien Quest

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2020 By DANIEL OBERHAUS -

Feature

FeatureDARTMOUTH SONGS

JANUARY 1963 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21 -

Feature

FeatureSTEVE KELLEY IN TWO ACTS

APRIL 1991 By ROBERT ESHMAN '82 -

Feature

FeatureDiary of a Long Distance Runner

SEPTEMBER 1987 By Tim Hartigan '87