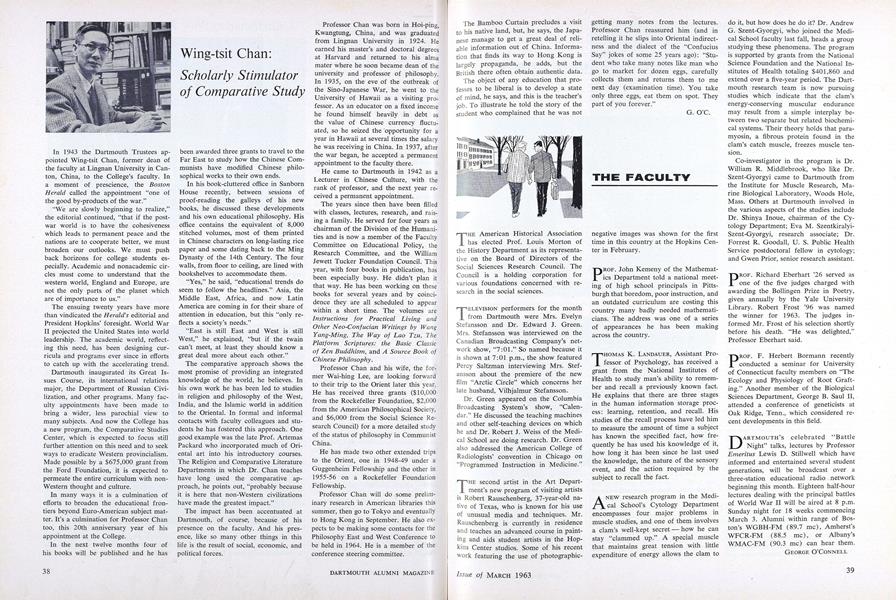

In 1943 the Dartmouth Trustees appointed Wing-tsit Chan, former dean of the faculty at Lingnan University in Canton, China, to the College's faculty. In a moment of prescience, the BostonHerald called the appointment "one of the good by-products of the war."

"We are slowly beginning to realize," the editorial continued, "that if the postwar world is to have the cohesiveness which leads to permanent peace and the nations are to cooperate better, we must broaden our outlooks. We must push back horizons for college students especially. Academic and nonacademic circles must come to understand that the western world, England and Europe, are not the only parts of the planet which are of importance to us."

The ensuing twenty years have more than vindicated the Herald's editorial and President Hopkins' foresight. World War II projected the United States into world leadership. The academic world, reflecting this need, has been designing curricula and programs ever since in efforts to catch up with the accelerating trend.

Dartmouth inaugurated its Great Issues Course, its international relations major, the Department of Russian Civilization, and other programs. Many faculty appointments have been made to bring a wider, less parochial view to many subjects. And now the College has a new program, the Comparative Studies Center, which is expected to focus still further attention on this need and to seek ways to eradicate Western provincialism. Made possible by a $675,000 grant from the Ford Foundation, it is expected to permeate the entire curriculum with non-Western thought and culture.

In many ways it is a culmination of efforts to broaden the educational frontiers beyond Euro-American subject matter. It's a culmination for Professor Chan too, this 20th anniversary year of his appointment at the College.

In the next twelve months four of his books will be published and he has been awarded three grants to travel to the Far East to study how the Chinese Communists have modified Chinese philosophical works to their own ends.

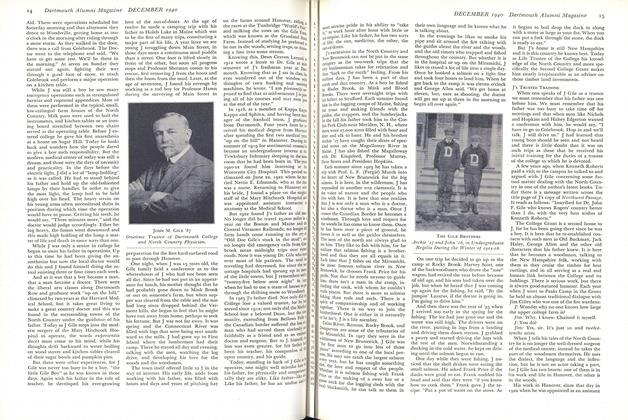

In his book-cluttered office in Sanborn House recently, between sessions of proof-reading the galleys of his new books, he discussed these developments and his own educational philosophy. His office contains the equivalent of 8,000 stitched volumes, most of them printed in Chinese characters on long-lasting rice paper and some dating back to the Ming Dynasty of the 14th Century. The four walls, from floor to ceiling, are lined with bookshelves to accommodate them.

"Yes," he said, "educational trends do seem to follow the headlines." Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and now Latin America are coming in for their share of attention in education, but this "only reflects a society's needs."

"East is still East and West is still West," he explained, "but if the twain can't meet, at least they should know a great deal more about each other."

The comparative approach shows the most promise of providing an integrated knowledge of the world, he believes. In his own work he has been led to studies in religion and philosophy of the West, India, and the Islamic world in addition to the Oriental. In formal and informal contacts with faculty colleagues and students he has fostered this approach. One good example was the late Prof. Artemas Packard who incorporated much of Oriental art into his introductory courses. The Religion and Comparative Literature Departments in which Dr. Chan teaches have long used the comparative approach, he points out, "probably because it is here that non-Western civilizations have made the greatest impact."

The impact has been accentuated at Dartmouth, of course, because of his presence on the faculty. And his presence, like so many other things in this life is the result of social, economic, and political forces.

Professor Chan was born in Hoi-ping, Kwangtung, China, and was graduated from Lingnan University in 1924. He earned his master's and doctoral degrees at Harvard and returned to his alma mater where he soon became dean of the university and professor of philosophy. In 1935, on the eve of the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War, he went to the University of Hawaii as a visiting professor. As an educator on a fixed income he found himself heavily in debt as the value of Chinese currency fluctuated, so he seized the opportunity for a year in Hawaii at several times the salary he was receiving in China. In 1937, after the war began, he accepted a permanent appointment to the faculty there.

He came to Dartmouth in 1942 as a Lecturer in Chinese Culture, with the rank of professor, and the next year received a permanent appointment.

The years since then have been filled with classes, lectures, research, and raising a family. He served for four years as chairman of the Division of the Humanities and is now a member of the Faculty Committee on Educational Policy, the Research Committee, and the William Jewett Tucker Foundation Council. This year, with four books in publication, has been especially busy. He didn't plan it that way. He has been working on these books for several years and by coincidence they are all scheduled to appear within a short time. The volumes are Instructions for Practical Living andOther Neo-Confucian Writings by WangYang-Ming, The Way of Lao Tzu, ThePlatform Scriptures: the Basic Classicof Zen Buddhism, and A Source Book ofChinese Philosophy.

Professor Chan and his wife, the former Wai-hing Lee, are looking forward to their trip to the Orient later this year. He has received three grants ($10,000 from the Rockefeller Foundation, $2,000 from the American Philosophical Society, and $6,000 from the Social Science Research Council) for a more detailed study of the status of philosophy in Communist China.

He has made two other extended trips to the Orient, one in 1948-49 under a Guggenheim Fellowship and the other in 1955-56 on a Rockefeller Foundation Fellowship.

Professor Chan will do some preliminary research in American libraries this summer, then go to Tokyo and eventually to Hong Kong in September. He also expects to be making some contacts for the Philosophy East and West Conference to be held in 1964. He is a member of the conference steering committee.

The Bamboo Curtain precludes a visit to his native land, but, he says, the Japanese manage to get a great deal of reliable information out of China. Information that finds its way to Hong Kong is largely propaganda, he adds, but the British there often obtain authentic data.

The object of any education that professes to be liberal is to develop a state of mind, he says, and this is the teacher's job. To illustrate he told the story of the student who complained that he was not

THE American Historical Association has elected Prof. Louis Morton of the History Department as its representative on the Board of Directors of the Social Sciences Research Council. The Council is a holding corporation for various foundations concerned with research in the social sciences.

TELEVISION performers for the month from Dartmouth were Mrs. Evelyn Stefansson and Dr. Edward J. Green. Mrs. Stefansson was interviewed on the Canadian Broadcasting Company's network show, "7:01." So named because it is shown at 7:01 p.m., the show featured Percy Saltzman interviewing Mrs. Stefansson about the premiere of the new film "Arctic Circle" which concerns her late husband, Vilhjalmur Stefansson.

Dr. Green appeared on the Columbia Broadcasting System's show, "Calendar." He discussed the teaching machines and other self-teaching devices on which he and Dr. Robert J. Weiss of the Medical School are doing research. Dr. Green also addressed the American College of Radiologists' convention in Chicago on "Programmed Instruction in Medicine."

THE second artist in the Art Department's new program of visiting artists is Robert Rauschenberg, 37-year-old native of Texas, who is known for his use of unusual media and techniques. Mr. Rauschenberg is currently in residence and teaches an advanced course in painting and aids student artists in the Hopkins Center studios. Some of his recent work featuring the use of photographic-getting many notes from the lectures. Professor Chan reassured him (and in retelling it he slips into Oriental indirectness and the dialect of the "Confucius Say" jokes of some 25 years ago): "Student who take many notes like man who go to market for dozen eggs, carefully collects them and returns them to me next day (examination time). You take only three eggs, eat them on spot. They part of you forever."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeaturePOETRY AT DARTMOUTH

March 1963 By RICHARD EBERHART '26 -

Feature

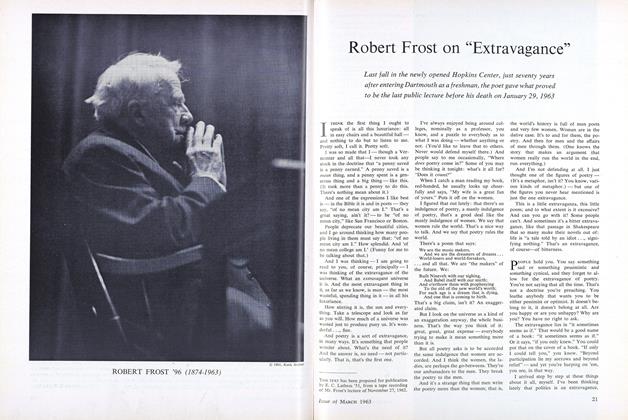

FeatureRobert Frost on "Extravagance"

March 1963 -

Feature

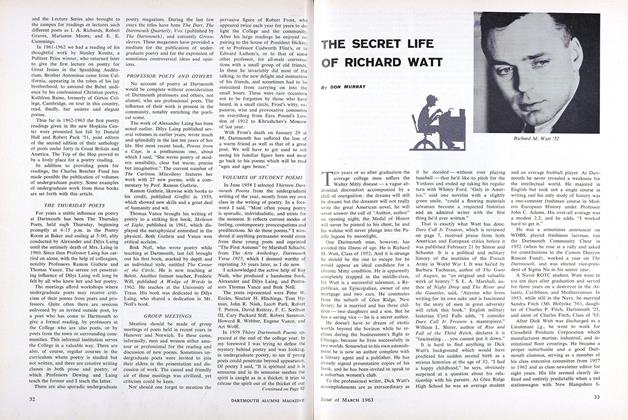

FeatureTHE SECRET LIFE OF RICHARD WATT

March 1963 By DON MURRAY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

March 1963 By JOHN HURD, HUGH M. MCKAY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

March 1963 By CHARLES F. MCGOUGHRAN, ALBERT W. FREY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1940

March 1963 By ROBERT W. MACMILLEN, DONALD G. RAINIE

G.O'C.

Article

-

Article

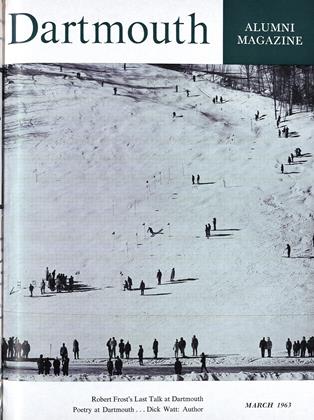

ArticleWINTER CARNIVAL—A NATIONAL EVENT

March 1916 -

Article

ArticleMen of 1942: What Can I Do?

August 1942 -

Article

ArticleVice President Harned resigns

MAY 1985 -

Article

ArticleParis Notes

October 1937 By George R. Hull '18 -

Article

ArticleJANITOR'S LIFE

December 1940 By ROBERT R. RODGERS '42 -

Article

ArticleIn Fine Fettle

June 1940 By The Editor