PROFESSOR OF ECONOMICS

AUTOMATION has been described as the "key with which we can leave this dim vault and walk out onto the upland pastures - the Elysian fields." The eloquent author of these lines may well be right. The future will give us a very positive answer. In the meantime, however, our journey to those bounteous upland pastures is marked by serious obstacles. These obstacles not only impede our progress but lessen the attractiveness of the vision that beckons us on.

Technological progress has seldom been an unmixed blessing. Along with its numerous benefits such progress, whether it takes the form of automation or of ordinary improvements in methods and machines, brings with it various problems. One of these problems is insecurity for the individual worker. Regardless of the long-run favorable effects of technological change on total employment, its short-run effects on the employment of specific individuals is often serious and tragic. Technological unemployment is therefore an unmistakable reality; its existence cannot be denied by any subtle process of definition.

In addition to technological improvements there have been other structural changes in American economic life. There have been mergers, and hints of mergers, a development that is causing serious industrial relations problems in the railroad industry, an industry in which the issue of technological change itself has recently been dramatized in a far-reaching Supreme Court decision; there have been numerous shifts in demand patterns, which have had adverse effects on employment in the coal mines of West Virginia and Pennsylvania, and in the defense plants of Michigan; there has been a depletion of certain natural resources in various areas, and again West Virginia and Pennsylvania will serve as examples; there have been geographical shifts in industry, including those that have taken place between New England and other parts of the country.

The insecurity that accompanies these changes is not always limited to individual workers. Sometimes there is also union insecurity, which is reflected in reduced membership rolls and declining dues payments. Then, too, there is often employer insecurity, consequent upon new forms of competition that these changes may involve and because of increased labor costs.

In light of these structural changes in our economy, and in view not only of the frequency of recessions during the last few years but also of the rapid growth in our labor force, it is not surprising that the workers and their leaders have become increasingly security-conscious. Nor is it surprising that they have been making all sorts of demands on employers - and on the government too —to the end that "the automation threat" be brought under control. When these demands cannot, or will not, be met by employers, industrial strife can easily develop, and a considerable amount of such strife has developed.

Some of the demands now being made by unions are quite old and have often been pressed before, and with some degree of success. Others are new and represent a fresh approach to a problem which, though it has long existed, has in recent years assumed a more serious form. To some of these demands, both old and new, we shall now turn our attention. Our analysis will relate primarily to unionized firms.

THE most widely and most persistently recommended policy for coping with the unemployment caused by automation is shorter hours. Many union leaders believe that automation has made shorter hours not only a possibility but a necessity, and over the last few years they have repeatedly contended that the length of the workweek should be reduced to 35 hours or thereabouts, with no reduction in take-home pay. At the same time the unions have demanded further liberalization of vacation benefits. Indeed, last September the United Steelworkers and the American and Continental Can companies entered into agreements providing for extra vacations in the form of periodic "sabbatical leaves." (The monopoly that academicians at Dartmouth and elsewhere have enjoyed in this area has been definitely broken.)

The unions have also been pressing for arrangements to make possible earlier retirements, thus hoping to create more jobs. They have also been demanding more individual holidays (though here the automation aspect does not seem to enter), and they have shown considerable ingenuity in discovering suitable days to celebrate. Not only is Washington's Birthday widely observed, but some workers now have a holiday on their own birthday; not only is the anniversary of the country's birth duly reconized, but in a few instances the worker's wedding an- niversary is also recognized.

Most of the recent union pressure for shorter hours is based on the belief that there is no longer enough work to go around. With automation progressing at a high speed and with population and the labor force growing at a rapid rate, the economy presumably is not able to provide gainful employment for all who are seeking it.

The unemployment argument for shorter hours is not without merit. A temporary reduction in hours, involving the use of the share-the-work and share-the-wage principles, is a useful expedient for dividing up the available jobs. This policy, as a matter of fact, has long been used by employers in combating seasonal and cyclical slumps. It could be used much more extensively, however.

A special aspect of the share-the-work policy has come into prominence in recent years. With many workers in the country unemployed, some companies have nevertheless preferred to work their present employees overtime rather than take on new workers. The growth of large fringe benefits has been a decisive factor in this development. Organized labor has been greatly disturbed by the policy, and the AFL-CIO, as a means of counteracting it, has urged that the Fair Labor Standards Act be changed to provide double time for overtime rather than the present time-and-a-half. A bill to this effect has been introduced in Congress by Representative O'Hara of Michigan. It is clear that unless the growth rate in the economy can be increased appreciably in the near future, the demand for alterations in our present overtime policies will be pushed with increasing vigor.

Temporarily reducing hours is one thing; permanently reducing them, with no change in take-home pay, is something else. It is quite possible that during the time a shift is being made from one hour level to another, the amount of unemployment will be reduced. But when industry becomes adjusted to the new hour plateau there will probably be as much unemployment as before. Historical evidence suggests that this is the case, and so does an analysis of the basic causes of unemployment: these causes are not eradicated by any change in the length of the workweek.

There are a number of other reasons why a permanent reduction of hours, at least if it is at all sizable, is undesirable. At a time when we are engaged in vigorous international trade competition a 14.3 per cent increase in hourly wage rates, which would be the result if hours were reduced from 40 to 35 with weekly wages remaining the same, would place us in economic jeopardy. Moreover, in view of Khrushchev's boast to bury us in the production battle, we cannot afford to adopt a policy that would adversely affect production.

Back in the 1890's, when the campaign for the eight-hour day was carried on with special vigor, two English authors, Sidney Webb and Harold Cox, declared that "experience shows that, in the arithmetic of labor ... two from ten is likely to produce, not eight, but even eleven.'' Strange things may indeed happen in the arithmetic of labor, and in some cases more goods might well have been produced in eight hours than in ten. But today there is no reason for believing that industrial output would be greater under a 35-hour week than under a 40-hour week. In fact, in the great bulk of cases production would probably suffer if hours were cut to 39 hours or to 38; that is, unless positive steps were taken at the same time by employers and labor to increase productivity. This has been done, it is interesting to note, in connection with hour reductions in Norway and Soviet Russia, and we could easily learn a lesson from these countries.

Advocacy of a permanent cut in hours at the present time is a counsel of desperation, though under the conditions of recent years the unions cannot be blamed for offering it. Furthermore, the unions will continue to give this counsel, they will continue to press strongly for shorter hours, unless the country's growth rate is speeded up. If we could raise this rate to four or five per cent per annum, we would hear much less about the need for reducing hours. In other words, a great deal of the recent pressure for shorter hours is really not due to automation but to a low level of production in the economy as a whole.

However, even when we return to a higher growth level the unions will continue to seek reductions in hours, though they will use other arguments. In view of the continuous increases in productivity, such a quest is quite logical. In the years that lie immediately ahead, therefore, management cannot expect to be free of union pressure for a still shorter workweek, for still longer vacations, and for still more paid holidays. From the stand-point of the general public, the employers, and the workers themselves, however, the progress toward these objectives should not be too rapid. It would be a major national calamity if all unions in this country were able to force a decrease in hours, and an increase in pay, comparable to what Local 3 of the Electrical Workers achieved in New York City.

A COMPARATIVELY new approach to the automation problem is the establishment of special funds for the benefit of workers adversely affected by major technological innovations. Among the better known of such funds are the Armour Automation Fund and the West Coast Longshore Mechanization and Modernization Fund. But there are others.

The automation funds that are now in existence vary a great deal in the benefits they confer. A remarkable thing about the benefits, however, is that they are designed largely for the workers who are retained in employment rather than for those who are displaced. Under the West Coast Longshore Fund, for example, the benefits take the form of a guaranteed weekly income for employed workers, payment of a lump sum at retirement, death or disability, and the granting of early retirement pay. (The first and third of these provisions may indirectly reduce the amount of labor displacement.)

Since it is the displaced workers who are particularly in need of help, the benefits under the automation funds should be expanded. There is nothing wrong with giving more to him that hath, but something should also be given to him that hath not. The displaced workers could be aided by these funds in a variety of ways, including retraining, separation pay, relocation costs (a provision found under the Armour Fund), and the continuance of certain benefit rights relating to such things as pensions and sickness. Many companies, of course, even without automation funds already aid the displaced workers in some of these ways.

The matter of financing automation funds is obviously of importance, and of concern, to the employer. A number of methods have been used in building up the funds, a common one being the gearing of contributions to output. The necessity of making payments into such a fund may represent a real hardship for the employer; unless, of course, his willingness to establish an automation fund results in the removal of union-imposed obstacles to technological change and in the active aid of his employees in increasing productivity. These benefits and others may well result from the existence of a fund. (In his valuable study, Automation Funds and Displaced Workers, Professor Thomas Kennedy deals with this matter and numerous other aspects of his subject.)

As an outgrowth of the Steel strike in 1959 the Steelworkers' Union and the Kaiser Steel Company established a committee to devise, if possible, a program for the equitable sharing of the future economic gains of the company. This committee is tripartite in nature, including as public representatives three of the country's leading labor experts. After almost three years of study the committee, at the end of 1962, recommended an "economic sharing plan." Referred to by the committee itself as a "significant breakthrough in the field of labor-management relations," the plan has commanded widespread attention. To Newsweek magazine it represents "the most intensive effort yet to solve the most perplexing labor-management problem of the times: Automation."

The plan contains a variety of provisions, a number of which relate specifically to the matter of insecurity. Though employees may be laid off because of a drop in business, they cannot be displaced as a result of improvements in technology and work methods. Protection is afforded to such workers through the creation of a plant-wide Employment Reserve. The company may use the workers in this reserve in whatever jobs it desires, but not to the disadvantage of other employees. The plan also provides for a wage guarantee when, as a consequence of technological innovations, hours are cut below 40 a week.

The "economic sharing" part of the plan provides that employees participate monthly in productivity gains. It makes no difference what factor or factors are responsible for the gains. Since labor costs have for some time been in the neighborhood of 32.5 per cent of total costs, the employees receive 32.5 per cent of any savings made in the costs of steel production.

The Kaiser plan is not an ordinary profit-sharing arrangement, of which there are hundreds in existence, since the gains accruing to the workers are not linked up with the profit position of the company. In terms of the sharing formula used, the Kaiser plan bears some resemblance to the so-called Scanlon plans. Examples of the latter have existed for quite some years though in disappointingly small numbers.

The other steel companies have not shown any interest in following the Kaiser example. But the chances are that the Steelworkers' union will attempt to spread the use of profit-sharing. And it is altogether likely that other unions too will press for the adoption of the Kaiser type of plan.

If these plans are to have a successful future it would be highly desirable to harness the interests and energies of the workers to a systematic program for reducing costs and increasing productivity, as is done under the Scanlon plans. It would also be desirable to re-examine the experience of the labor-management committees set up during World War II. Something useful might be found in that experience.

THOUGH not designed specifically to cope with "the automation threat," the 1961 agreement between American Motors and the United Automobile Workers has provisions in it that give employees greater security. Supplementary unemployment benefits have been increased, short workweek benefits have been provided, and other policies have been adopted. The profit-sharing feature of the agreement - or, as the company prefers to call it, the "progress-sharing" feature — is the one that has aroused most interest.

During the first year of the profit-sharing plan the company paid its workers $9,766,907 out of profits. Of this sum one-third took the form of shares of stock in the company (on the average each employee received stock worth close to $129) and two-thirds were directed to improvements in pensions, etc. Salaried employees of the company have a plan of their own but similar to the one for production workers.

Profit-sharing is not new in this country, but it is new in the automobile industry. Whether it will be introduced into the other companies in the industry remains to be seen. President Walter Reuther has stated that profit-sharing will be a major objective of his union in its bargaining negotiations in 1964.

The growing complexity of the issues subject to collective bargaining makes it increasingly desirable for management and unions to study carefully these issues long before their labor agreements expire. Under the Taft-Hartley law either party wishing to change or drop an existing agreement must notify the other 60 days before the expiration date, and the two parties are obligated to start the bargaining process at once. But more time is often needed - and a new "approach" is required — if the involved issues, including those posed by automation, are to be adequately explored. This fact is being more widely recognized, and a number of "continuous-study plans" have been put into operation.

One such plan is that adopted in the Steel industry after the strike of 1959. Under this plan there is a joint Human Relations Committee, composed of representatives of the eleven major Steel companies and the Steelworkers' union. The committee, with the help of sub-committees, has probed into such matters as wage incentives, job descriptions, and outside contracting. The function of the committee is not to engage in collective bargaining but to study and discuss matters of joint interest and concern. Obviously these will ordinarily be fit subjects for collective bargaining later on.

In an economy in which technological and other kinds of structural changes are the order of the day, in which international trade and balance of payment problems are of great importance, and in which a struggle with a determined political and economic adversary is under way — in such an economy there is a great need for a re-examination of the collective bargaining, and collective dealing, process. The Human Relations Committee in the Steel industry represents a step in that direction. If it can help to eliminate "crisis bargaining," which has so often characterized labor negotiations in recent years, it will have made a notable contribution.

THE unions, confronted with what they feel is a serious threat to their own security and the security of their members, have pressed for the adoption not only of broad plans such as those we have noted but for many narrower objectives. They have demanded that emloyers promote retraining programs for their technologically displaced workers a step that many employers have taken on their own volition. They have argued that seniority units should be widened so that displaced workers will have a larger area over which to exercise their seniority rights. They have insisted that severancepay plans be adopted, or liberalized, so that workers who are permanently laid off because of technological innovations or for other reasons will receive a special payment from their employer.

The unions, moreover, have demanded that employers pay transportation costs for their workers who are shifted to new plants. They have also demanded that supplementary unemployment benefits be paid, or, where such plans already exist, that the amount of the benefits be increased. They have declared that management should consult with the union before introducing technological innovations, a policy that is often followed.

Though not all union leaders look at the matter this way, the claim is now being made (not that it is entirely new) that the workers have a "property right" in their jobs. This notion if given the legal backing accorded to ordinary property rights would have truly immense implications, but such backing is not likely to be forthcoming. However, in a limited way some recognition is being granted to the central idea involved. We have reached a point where the so-called "human costs" of technological progress are receiving increasing attention.

In part these costs are now being met by the adoption of policies which the unions have demanded - and which they will continue to demand - or which employers themselves have adopted. To some degree they are also being met by governmental programs. To no small ex- tent, however, the costs go unrecognized and the victims of technological change - who, in John Stuart Mill's old but apt words, are "sacrificed to the gains of their fellow-citizens and of posterity" - bear the costs themselves.

BUT this whole matter of costs raises a highly important issue in applied industrial relations, an issue on which we shall end our discussion. The human costs of technological progress while they cannot all be paid for by money, nevertheless involve money outlays. For the most part the unions expect these outlays to be made by employers. But employers are not always in a position to meet the costs. It is here that a nice problem arises: Can plans be formulated which, by means of united action on the part of unions and management, will supply the funds to meet the costs? In other words, can the "conflict" ingredient in industrial relations be substantially replaced by a "cooperative" ingredient?

The question we have just asked suggests one of the most challenging problems in the whole field of industrial relations. But it is an extremely difficult problem - difficult not only because it is highly complex and ever changing, but because it is often encrusted with ingrained prejudices and unpleasant memories of the past. Moreover, it is a difficult question because it involves a definite conflict of interests. It is obvious that a problem of such magnitude can be solved only by the joint efforts of imaginative, enlightened, and tolerant union and business leaders. In some instances the aid of interested and capable outsiders might be of help, as it was, for example, in the formulation of the Kaiser and Armour plans.

It has been said, poetically, that "New times demand new measures and new men." The statement possesses a great deal of truth. Certainly in a world of far-reaching technological changes, and one of international stresses and strains, there is a pressing need in the field of industrial relations for experimentation with new methods as well as for further use of effective old methods. The task here does not necessarily call for "new men" but it does call for new attitudes.

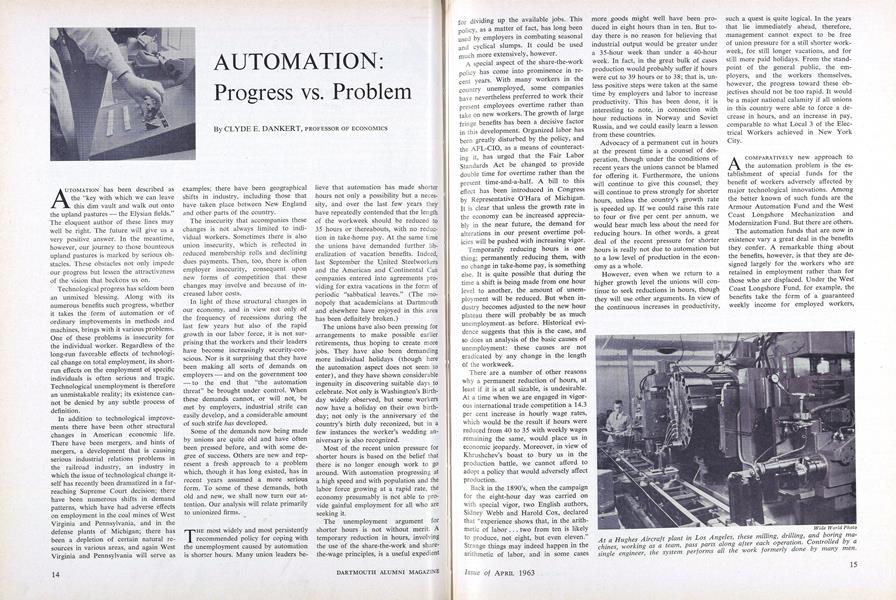

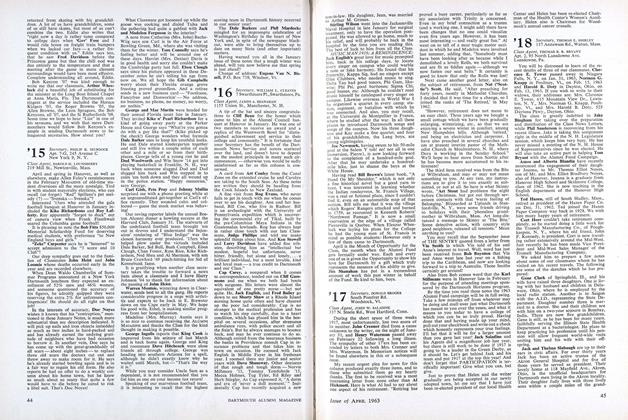

At a Hushes Aircraft plant in Los Angeles, these milling, drilling, and boringchines working as a team, pass parts along after each operation. Controlled by asingle engineer, the system performs all the work formerly done by many men.

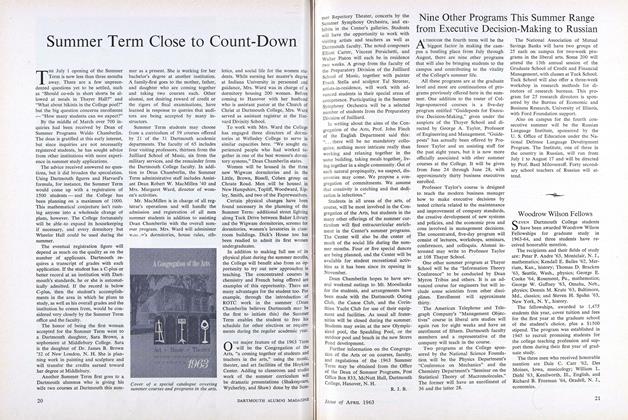

A remarkable instance of automation isthis Burroughs Sensimatic memory unitcontrolling an automatic factory 120miles away. The operator is directing thespray painting of components in a rangeof colors, the machining of engine parts,and the paper work at the installation.

THE AUTHOR: Clyde E. Dankert, M.A. '40, Professor of Economics and Chairman of the Social Sciences Division, has long been interested in the economic aspects of technological change. One of the earliest of his numerous articles on the subject appeared in the ALUMNI MAGAZINE of March 1933. His article on "Automation and Unemployment" was part of Studies in Unemployment issued by a special committee of the U. S. Senate in 1960. During the last few years he has probed into the question of hours of work, and he is chairman of an editorial committee preparing a volume on Hours of Work under the auspices of the Industrial Relations Research Association. A member of the Dartmouth faculty since 1930 and full professor since 1940, Professor Dankert teaches courses in labor economics, labor problems and public policy, and the history of economic thought. He is the author of two books, Contemporary Unionism in the United States (1948) and An Introduction to Labor (1954), both published by Prentice-Hall. A shorter work, Thoughts from AdamSmith, has just been published by the Stinehour Press. In addition to teaching and writing, Professor Dankert has occasionally been called upon to serve as a labor arbitrator.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDARTMOUTH SONGS

April 1963 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21 -

Feature

FeatureSummer Term Close to Count-Down

April 1963 By R.J.B. -

Feature

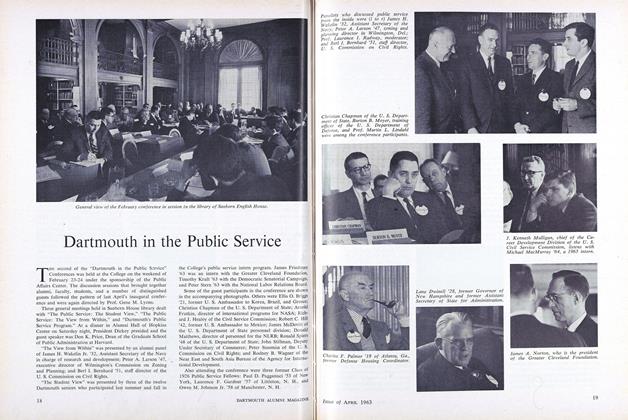

FeatureDartmouth in the Public Service

April 1963 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1922

April 1963 By LEONARD E. MORRISSEY, CARTER H. HOYT -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

April 1963 By CARL MAVES '63 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

April 1963 By THOMAS E. SHIRLEY, THOMAS B.R. BRYANT

Features

-

Feature

FeatureRobert S. Oelman '31 Heads Alumni Council for 1954-55

July 1954 -

Feature

FeatureMaster Translator

APRIL 1968 -

Feature

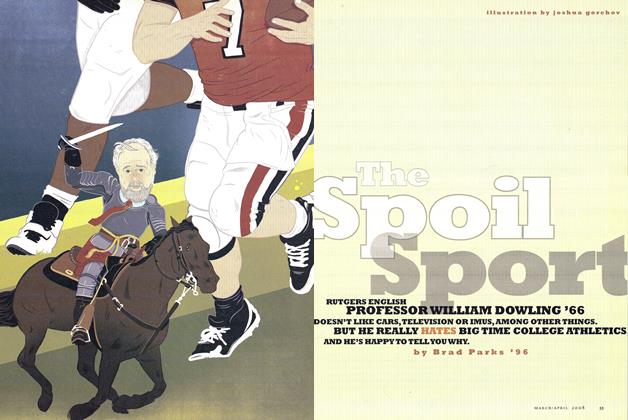

FeatureThe Spoil Sport

Mar/Apr 2008 By Brad Parks '96 -

FEATURES

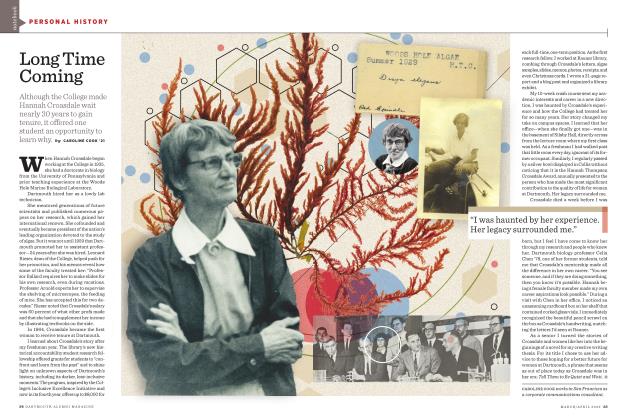

FEATURESLong Time Coming

MARCH/APRIL 2023 By CAROLINE COOK ’21 -

Feature

FeatureWe Were Soldiers

Mar/Apr 2003 By CASEY NOGA '00 -

Feature

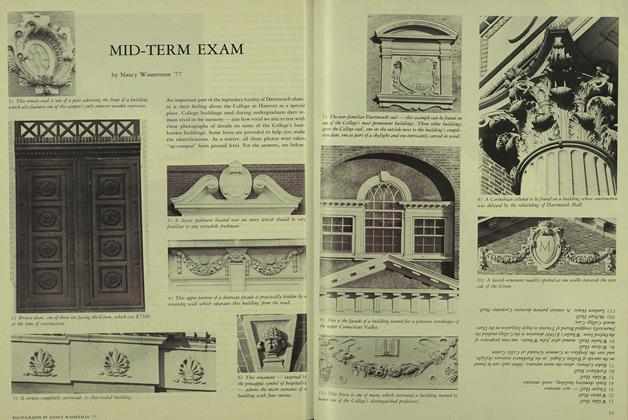

FeatureMID-TERM EXAM

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1983 By Nancy Wasserman '77