THE constant effort to keep a Dartmouth education within reach of the boy of limited means, and in some cases no means at all, is as old as the College itself. In the past dozen years, however, a special chapter has been written in the story of financial aid; both by design and by necessity, as the cost of going to college has climbed, the Dartmouth program of scholarships and loans has undergone a remarkable expansion. This year the total of Dartmouth's undergraduate scholarship grants has exceeded $1,000,000 for the first time, and in addition nearly $375,000 is being allocated in student loans. In the years ahead these figures are likely to go in only one direction - up.

In order to provide scholarship grants of a million dollars to 800 students, or 26% of this year's undergraduate enrollment, the College is using approximately $400,000 of its general operating funds to supplement the $600,000 of endowment income and gifts specifically earmarked for scholarships. As the College's basic charges - tuition, fees, board, and average room rent - have climbed from $1450 ten years ago to $2575 this year ($2725 next year) the Trustees have allocated more and more general funds to financial aid, so the percentage of scholarship boys at Dartmouth would not decline. Indeed, the College at present is studying the question of finding the funds that will enable it to do more than hold its ground on the scholarship front and will permit it to move forward again in the percentage of highly qualified boys of limited means enrolled in the College.

What is the purpose behind a financial aid program that involves a steadily increasing amount of money and now stands at $1,375,000 annually for scholarships and loans combined? The simplest answer is that Dartmouth's own self-interest is deeply involved, entirely aside from what scholarships and loans and jobs have meant in the lives of thousands of young men who are and were recipients of such help.

In the words of Robert K. Hage '35, director of Dartmouth's Office of Financial Aid, "The real goal of our student aid program, in alliance with the aims of the Admissions Office, is to support the educational purposes of the College by providing the finest possible student body. This means young men selected on personal ability and quality, regardless of the financial status of their families, which in turn means a student body having greater diversity in economic and geographical background and in social experience. President Hopkins used to speak of the educational value of 'the impact of youthful mind on youthful mind,' and without scholarship men this tremendously important side of the Dartmouth educational experience would certainly be the poorer. I know what our financial aid means to hundreds of very fine boys who would not otherwise be here at Dartmouth, but this is far from a oneway benefit; the College is also benefiting itself, and perhaps in the bigger way."

In a 1963 report Mr. Hage reviewed the previous ten years of financial aid operations at Dartmouth and pointed out that it is doubtful if any other area of college administration has witnessed more profound changes, not only at Dartmouth but at all institutions of higher learning.

Among the significant developments at Dartmouth in that decade, the undergraduate scholarship budget was nearly tripled - from $354,000 in 1952-53 to $907,000 in 1962-63, a figure that has now gone beyond the million-dollar mark. In that earlier year the College made scholarship grants to 481 undergraduates or 17% of all students. Aid given to the entering freshman class was at about the same level— 120 grants or 16% of the class. The next year, 1953-54, saw a dramatic jump in the extent to which the entering class was given scholarship aid - 182 grants to 25% of the class. This "move forward" was the result of carefully considered action on the part of the Dartmouth Trustees, who were aware that the number of scholarship applicants was steadily growing and that Dartmouth was falling behind the other Ivy colleges in the aid being provided.

Scholarship grants at the new level were maintained for succeeding entering classes and in a four-year period the percentage of all undergraduates getting scholarship aid had risen to 24%. The figures for the present year are somewhat higher - 27 % for the entering class and 26% for the undergraduate body as a whole - but there has been no marked fluctuation in the percentages, even though the number of men helped has increased (from 690 to 800 in the past seven years) and the size of the financial aid budget has grown considerably. The average scholarship grant ten years ago was $752: since then, at two-year intervals, it has gone up to $886 in 1955-56, to $1020 in 1957-58, to $1113 in 1959-60, to $1207 in 1961-62, to $1268 this year. Each of these jumps was primarily a response to an increase in basic College charges.

But outright scholarship grants are by no means the whole story of financial aid at Dartmouth. The element of "self-help" has played an increasingly important part in the program in recent years and has enabled the College to stretch its aid funds over a larger segment of the student body than it could otherwise have done. In the great majority of scholarship cases, the aid provided by the College is in the form of a "package" of scholarship plus loan, or scholarship plus assigned job, or a combination of all three. And then there are the needy non-scholarship students to whom the College is able to grant only loans.

Last year, for example, of the 789 men who received scholarship grants, 583 had part of their overall aid allotment in the form of loans to be repaid after graduation. Many of the remaining 206 were aided with a combination of scholarship and employment, usually a job for board at Thayer Hall. And to the 789 scholarship men last year were added 130 undergraduates who received loans only, making a total of 919 on the financial aid list and boosting to 30% the portion of the entire student body getting some form of aid directly from the College.

"The increase in loans to undergraduates is perhaps the most spectacular single element in the financial aid picture of the past ten years," Mr. Hage stated in his 1963 report. In 1952-53, undergraduate loans of $57,600 amounted to 14% of that year's scholarships; this year, loans of $375,000 amount to 37% of the scholarship total.

The sharp increase in loans since 1958-59 has resulted primarily from the advent of the National Defense Student Loan program and the concerted effort of the Ivy colleges to use loans to a greater extent as part of the financial aid "packages" for freshmen. In 1958-59, the College made loans to 402 men in the average amount of $345; last year, the total number of loans, with or without scholarship, was 713 and the average amount was $470. The great reliance currently being placed upon the government's NDSL program is indicated by this breakdown of last year's loan total of $337,305: the sum of $229,280 came from NDSL, $68,410 from the College's loan funds, and $39,615 from the alumni-sponsored Dartmouth Educational Association. Long before the advent of the National Defense program, the Dartmouth Educational Association, founded 67 years ago, was the most important single loan fund providing aid for undergraduates, and today it still plays an invaluable role in Dartmouth's financial aid program.

During the past ten years the loan limit for undergraduates has risen from $1200 for the four-year period to $4000 ($l000 a year), which conforms to the present NDSL maximum.

The total of Dartmouth student loans outstanding as of June 30, 1963 was $ 1 ,- 710,284, a rise of $335,000 over the previous year. A few borrowers, once graduated are inclined to forget how the loan funds helped them to get through college, but this fortunately is not the prevailing attitude. Recently a senior dropped into the Financial Aid Office to find out how much he was going to owe the College for his loans during four years. When told the amount, he cheerfully said, "$1800 - I got a $12,000 education here and I owe only $1800 that's not a bad deal."

Loans, especially with NDSL funds available, are not in as short supply as scholarship funds and jobs for Dartmouth's needy students. Job opportunities are definitely limited because Hanover is an academic rather than a commercial town. The Financial Aid Office, which formerly was responsible only for Dartmouth Dining Association employment, now serves as the clearing house for all student jobs, under the supervision of William C. Quimby '52, assistant director of financial aid, and is thus able to coordinate this form of self-help with the monetary grants from the College. Assigning students to DDA jobs for their meals is the major employment asset the Financial Aid Office has. About 200 dining hall jobs are available, but because most men work only two of the three terms, to spread the work, 300 men can be given DDA jobs as part of their aid packages. The $20,000 a year provided by the William N. Cohen Fund is used to reduce the student's work load to thirteen hours a week for full board. Total student earnings during the college year are not reliably known, but with College jobs figured at approximately $230,000 it is reasonable to place the total at well over $300,000.

The College's own three-part program of financial aid - scholarships, loans, and jobs - gets an important assist from another significant development of the past decade: the growth in awards from corporations and related foundations made directly to students for use at the colleges-of their choice. General Motors National Scholarships and the National Merit Scholarships have been leaders in this area in the past ten years. Such scholarships sometimes carry an additional grant-in-aid to the College itself.

In addition to the men receiving "outside" help in the form of corporation scholarships, about ninety regular NROTC students each year get full-tuition grants plus certain allowances, and more than 150 other ROTC students get monthly subsistence payments. Benefits from the federal and state governments aid a few men each year, foreign students get a variety of grants from their home governments or organizations in this country, and then there are a multitude of smaller grants from special funds, Rotary, PTA, and the like. It is estimated that when all the undergraduates getting some form of outside help are added to the number receiving aid from the College, the total approximates 40% of the entire student body.

One special virtue of the increased amount of outside aid during the past decade is that it has helped to take some of the pressure off the College as the number of scholarship applicants has skyrocketed in a period of rising costs. Of the 3723 men who completed applications for the present freshman class, 1651 asked for scholarship aid —an increase of more than 100% over the 791 men who requested aid in the Class of 1956. Of the 1324 men to whom admission was offered, 676 or 51% were financial aid applicants. Taking into account the usual attrition, the College offered aid of some form to 442, and 274 actually matriculated.

The decision as to who gets financial aid and how much is essentially an independent operation, but the work of both the Admissions and the Financial Aid Offices is closely integrated, with common objectives and a pooling of information. Although financial aid at Dart- mouth is not awarded as a prize but is based upon need, a great deal more than cold arithmetic goes into the decisions. With more aid applicants than can be accommodated, the total record of each applicant - with regard to academic promise, other achievements, and personal qualities —• is carefully evaluated. Need is the prime consideration, however, and aid may range from $2OO up to the full cost of a Dartmouth Applicants of exceptional qualifica- tions may be given such honor awards as the Daniel Webster National Scholarships, the Alfred P. Sloan National Scholarships, or the Dartmouth alumni club and regional scholarships.

In figuring the amount of aid needed by a student this year, the Financial Aid Office took $3050, plus travel, as a reasonable total of college costs for a scholarship man. (Next year it will be $3200.) This includes $1675 tuition, $500 board, $400 room, and $475 for the rest of his expenses. The applicant is usually expected to provide $800 to $900 of this by his own efforts - summer work, term work, and a College loan to be repaid out of future earnings. A fair contribution from his parents' income and assets is figured from the complete information filed with the College Scholarship Service. One-fifth of any student savings at the time of application is figured in, along with any other resources reported, and the balance of the $3050 plus travel that is not covered determines the size of the scholarship grant.

The College Scholarship Service, the central agency with which family financial statements are filed, is now used by some 500 colleges and is a good example of the extent to which intercollegiate cooperation in financial aid administration has developed during the past decade. Mr. Hage, for some years a member of the CSS directing committee and chairman of the subcommittee on computation that set up standards for parents' contributions in varying circumstances, has been one of the national leaders in this move toward cooperation. Not only does Dartmouth participate in the College Scholarship Service but it consults regularly with colleges likely to have common candidates for aid.

Mr. Hage as Dartmouth's financial aid director leads an extremely busy life both locally and nationally. But he likes to put aside details when he can and dwell on the broader consideration of what financial aid means to the College. A year ago he got to thinking about the campus leadership provided by scholarship men, so he dug into his files for that year and found that scholarship men, besides having a combined academic average above that for the College as a whole, held these positions: president and vice president of the Undergraduate Council; chairman of Palaeopitus; presidents of the senior class and junior class; president, treasurer, and secretary of Green Key; president, vice president, and treasurer of the Interfraternity Council; president and vice president of the Inter- dormitory Council; president, vice president, and managing editor of The Dartmouth; editor of Jack-o-Lantern; president and vice president of the Forensic Union; president of the Band; vice president of the Dartmouth Christian Union; captains of basketball, football, lacrosse, rifle, rugby, skiing, and wrestling; managers of football, hockey, lacrosse, and rowing; head cheerleader; and the winner of the Barrett Cup.

Of course, as Mr. Hage is quick to point out, this was undoubtedly a very good year for scholarship men, but he has no doubt that year in and year out scholarship men contribute mightily to the vitality of Dartmouth life. Faculty members assert, and the records support, the fact of contemporary academic life that scholarships are a self-interested investment in human potential that the College can't afford to pass up.

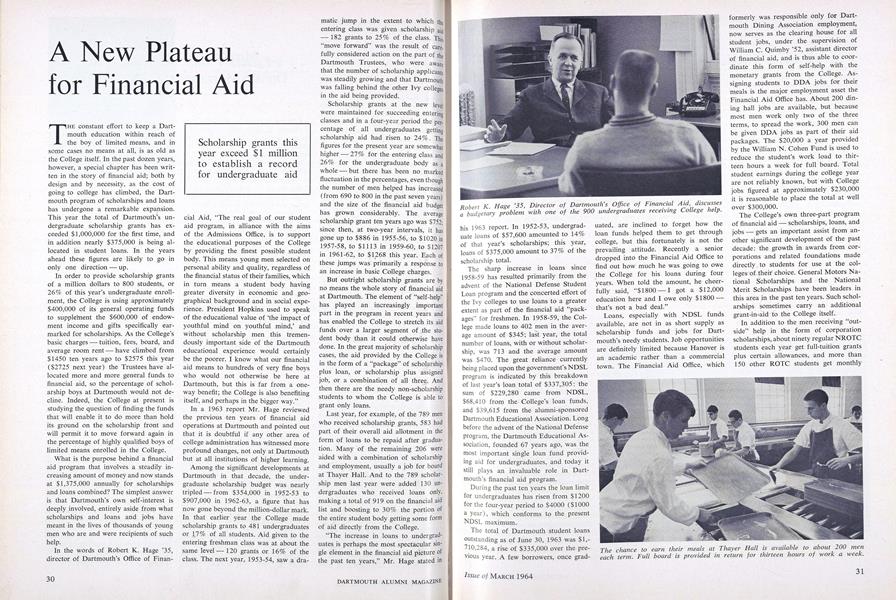

Robert K. Hage '35, Director of Dartmouth's Office of Financial Aid discussesa budgetary problem with one of the 900 undergraduates receiving College help.

The chance to earn their meals at Thayer Hall is available to about 200 meneach term. Full board is provided in return for thirteen hours of work a week.

Scholarship grants this year exceed $1 million to establish a record for undergraduate aid

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTHE COMMUNITY COLLEGE

March 1964 By THOMAS E. O'CONNELL '50 -

Feature

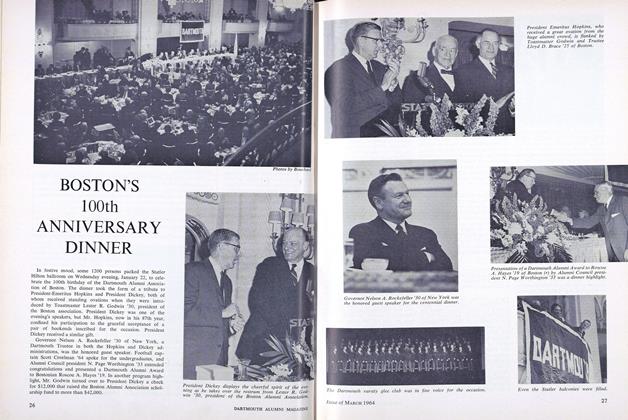

FeatureBOSTON'S 100th ANNIVERSARY DINNER

March 1964 -

Article

ArticleA graduate of 1804 who stood up for an American Culture

March 1964 By BEN HARRIS McCLARY -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

March 1964 By DAVE BOLDT '63 -

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

March 1964 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

March 1964 By THOMAS E. SHIRLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER

Features

-

Feature

FeatureCOMMENCEMENT

July 1961 -

Feature

FeatureClass Association Delegates Meet to Discuss Coeducation

JULY 1971 -

Cover Story

Cover StorySartorial Splendor

April 1981 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryQuite Good

MARCH 1995 By Abner Oakes IV '81 -

Feature

FeatureCARSON

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Brad M. Hutensky '84 -

Features

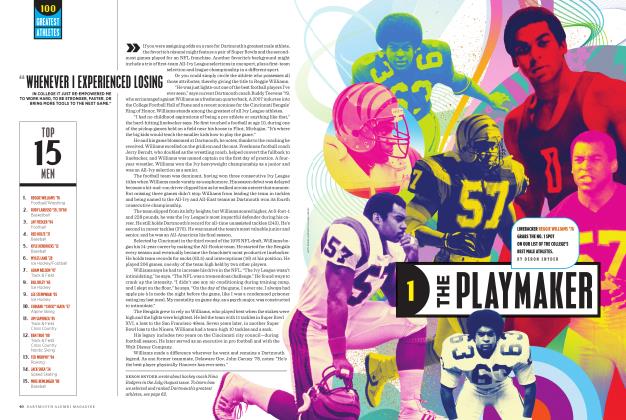

FeaturesThe Playmaker

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2022 By DERON SNYDER