An unprecedented exhibit at the Hood explores gender roles and the family in eighteenth-century France, and raises some contemporary questions.

SHOULD WOMEN STAY AT HOME with their children? Is it the government's responsibility to address the problem of "dead-beat dads"? Was the "coming out" episode of Ellen a primetime moral victory, or a national disgrace? As a society, we struggle to define gender roles, wrestle with state involvement in our families, and perceive popular culture as a powerful tool for social and moral

guidance. The very same topics were debated more than 200 years ago in France, and you can see the issues played out on canvas in a new exhibition at the Hood Museum of Art: "Intimate Encounters: Love and Domesticity in Eighteenth-Century France." Open from October 4, 1997 through January 4, 1998, this is the first major exhibition devoted solely to eighteenth-century French genre images. Curator Richard Rand and assistant Juliette Bianco '94 have assembled the works from North American and European collections, including the Hood's first loan from the Louvre.

In the early 1700s, France's influential Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture reserved its highest accolades for historical painting. Dra- matic figures from classical and Biblical history presented the public with characters the Academy deemed appropriate to morally instruct and inspire. Meanwhile, genre paintings a "pop culture" equivalent which portrayed scenes from everyday life were beginning to depict the human figure in a different way. Often beautifully rendered, the images showed men and women of the aristocracy engaged in frivolous, sometimes erotic, pursuits; decorative and playful allegories of romantic love, full of the tension and role-playing of courtship. "The Academy considered these works to be morally inferior, and therefore discouraged them," says Rand.

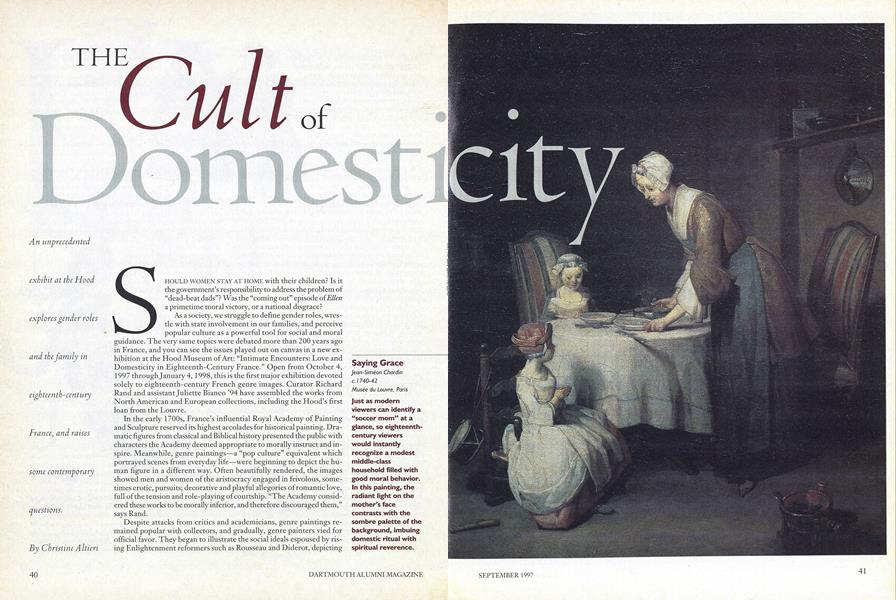

Despite attacks from critics and academicians, genre paintings remained popular with collectors, and gradually, genre painters vied for official favor. They began to illustrate the social ideals espoused by rising Enlightenment reformers such as Rousseau and Diderot, depicting idealized images of the family, regardless of class. "No one in the eighteenth century would see these scenes as simply mirrors of reality," Rand states In keeping with Enlightenment philosophy, the genre painters captured the grace of domestic serenity, the order of gender-specific activities, and the strength of conjugal love. In Saying Grace, for example, the mother's lace is lit as if from a heavenly source, as she directs a keenly nurturing and loving gaze toward her young son. In Portrait of the Devil Family the child is placed mloving security between his mother and father, clutching his windmill toy in one hand while reaching for sweets with the other. These are images of love as the force that binds the social contract between two people, as in turn, each family was expected to bind the nation as a whole.

By the end of the century the old social contract had come undone wrenched apart by the French Revolution. The philosophical and moral debates raised in paint during the preceding century were settled by the guillotine. In 1793 even the influential Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture was dismantled. When it re-opened after the revolution, there were few rules, and any painter could join

Beautiful and allegorical, this exhibition's images reveal a nation on the cusp of dramatic change. They address familiar and important issues which remain provocative, persistent, and elusive for society to resolve.

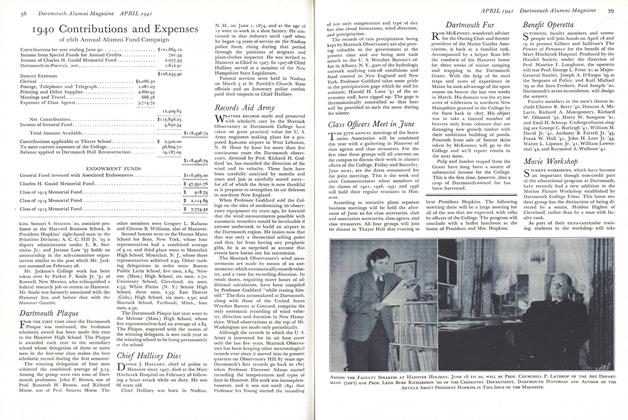

Saying Grace Jean-Simeon Chardin c. 1740-42 Musee du Louvre, Paris

just as modern viewers can identify a "soccer mom" at a glance, so eighteenthcentury viewers would instantly recognize a modest middle-class household filled with good moral behavior. In this painting, the radiant light on the mother's face contrasts with the sombre palette of the background, imbuing domestic ritual with spiritual reverence.

Portrait of the Devin Family

Louis-Michel Van Loo 1767 Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Jean-Jacques Julien and his demure Comtesse are the model for "family values." The briefcase marks Dad as a responsible member of the professional class. Since society proscribed women from idleness and intellectual audacity, Mom's needlepoint affirms her office. The richly-dressed child is the emotional link between the divergent roles of his parents.

Blindman's Buff

Jean-Honore Fragonard c. 1753-56 Toledo Museum of Art

This lush, aristocratic fantasy of a saucy milkmaid and a faux shepherd suggests the sort of fun a gal in a tight-fitting red dress might find in the abandon of the out-of- doors. Eighteenth- century viewers would immediately grasp the sexual symbolism of the rope and the bucket.

Christine Altieri coordinates art and production for this magazine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

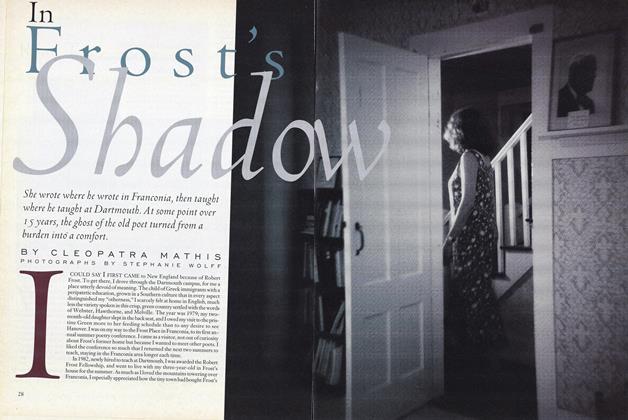

Cover StoryIn Frost's Shadow

September 1997 By CLEOPATRA MATHIS -

Feature

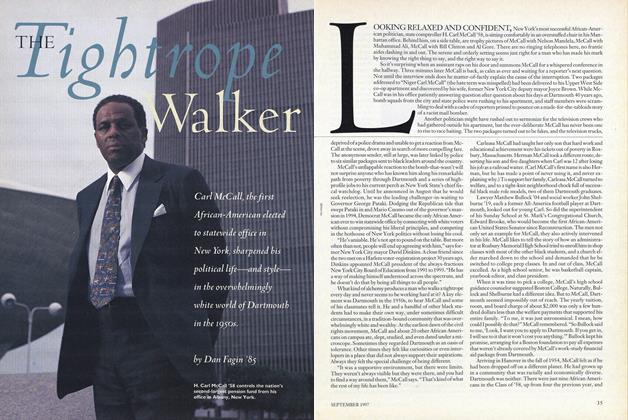

FeatureThe Tightrope

September 1997 By Dan Fagin '85 -

Feature

FeatureUninight

September 1997 By DOUGALD MACDONALD '82 -

Article

ArticleRoad Trip

September 1997 By Sarah Moore -

Article

ArticleElevator Going Up, AstroTurf Going Down

September 1997 By "E. Wheelock." -

Article

ArticleEnvironmental Impact

September 1997 By Noel Perrin

Features

-

Feature

Feature1940 Contributions and Expenses of 26th Annual Alumni Fund Campaign

April 1941 -

Feature

FeatureDinner at Dartmouth

July/Aug 2003 -

Feature

FeaturePsycho-Social Dynamics and the Prospects for Mankind

DECEMBER 1983 By Charles E. Osgood '39 -

Feature

FeatureThe Ultimate Guide

Jan/Feb 2013 By MARGARET WHEELER AS TOLD TO JIM COLLINS '84 -

Feature

FeatureHard times in the pressure-cooker

DECEMBER 1981 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureThe New Classics

MARCH 1978 By Shelby Grantham