EDITOR, THE TIMES OF LONDON

WE thank you for having asked us to join you in this convocation to discuss great issues in the Anglo-Canadian-American Community. It seems to me significant that Dartmouth College, now only twelve years short of its Bicentennial, should have added to its fame throughout the world by those particular words "Great Issues." All words are fascinating. But they are rather like the faces of our friends. We think we know them so well that we take them for granted. We never pause to look at them closely.

In the Oxford English Dictionary there are 36 different meanings recorded for the noun issue. The idea of its being a point of contention, of there being matter for argument, is the oldest of them. There is perhaps nothing startling in that. What is startling is that so ancient an idea - and of course it goes back for thousands of years before the brief English archives of a mere ten centuries or so - should in our own day be so desperately fighting for its existence.

Over great parts of the world all the powers of intimidation, of oppression, of newly found mental weapons and old-fashioned physical ones are being used to persuade the ordinary man and woman that in many fields of inspiration and thought there can be no issues whatever. And in some of our own parts of the world, although no one anywhere in it would wish to be "cobbling at manacles for all mankind," there are those who would like to enforce the same discipline, albeit in a much more restricted area. . . .

The trouble with freedom of thought, as John Morley pointed out sixty years ago, is that even its most fervent advocates, who have advanced its cause in every age, have always set limits. Milton's idea of freedom stopped short at what he considered superstition. Locke broadened this out but balked at "opinions contrary to human society." Mill excluded from his liberty "those backward stages of society in which the race itself may be considered as in its nonage." And we could in our own countries draw up a similar list of exceptions today. But, the martyrdom of man - it is also the ennoblement of man - has taught us one thing. Whatever dictators or oligarchies may ordain, however much it may temporarily be brow-beaten or imprisoned, the mind of man will, in the long run, accept no limits. The search for truth is not only endless, but boundless. It extends to what in every generation we can most deeply believe is truth itself. The whole fight for truth is a fight for the right to question accepted things. Nothing can stay unquestioned forever. . . .

And here, although it is rather on the margin of my theme, I would like to make a short digression. It is as vital to maintain the freedom to question, to criticize, and even to differ, between nations as within nations. Above all, between friendly nations. All too often, dismay and anger, and what the newspapers and radio represent as near-crisis, are engendered because one ally temporarily cannot see eye to eye with another. Even between the closest of friends there are bound to come honest differences of opinion. There must be room for them within every alliance. They do not matter in themselves. What matters is the spirit in which they are dealt with - and the way in which they are presented to the people. There can be no true alliance without some mental jostling, and arguing, and conflicts of interest. They need not cause hysterical headlines. They are not calls to national pride or to the old Adam that is in all of us. If they are discussed calmly and rationally they can strengthen the alliance by increasing its understanding.

We cannot, however, merely establish the principle of freedom of thought, of there being great issues between societies, within society, and in each individual human soul, and then rest content. Even if we managed to open up substantially the field of discussion in our generation our task would not be done. Were the search for truth ever to become unimpeded in every direction, and man be free to conduct it openly, no matter where he willed; that would not be enough. He has to have the will.

An even greater danger than those who seek to close the human mind are the minds, young and old, that close themselves. The manifest enemies of freedom of thought we can always combat. But here we have an enemy that is not so manifest. It is less easily combated. As we can never know the exact measure of the threat it is often not combated at all. . . .

There is only one way to keep this cancer on freedom of thought —it is really an over-proliferation of the cells of apathy - at bay. It must be done by education; and by the realization that the process of education is endless. Your own Great Issues Course springs from this conviction. It is a bridge between the academic curriculum and the lessons that will have to be learned in the outside world. But far more important than the lessons themselves is the question what is to be, for the ordinary man, their range and scope.

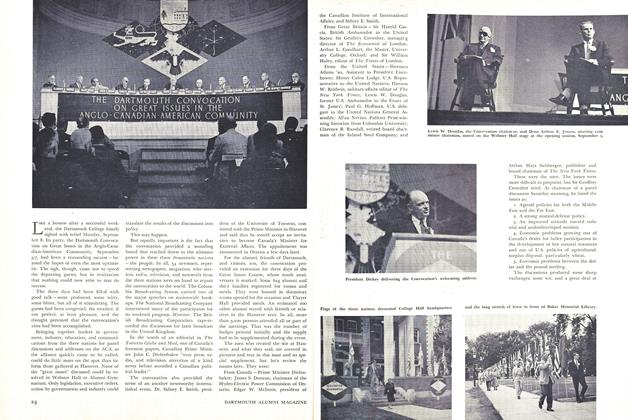

This convocation, which is now coming to its end, has been concerned with our Anglo-Canadian-American Community. Its purpose has been to seek out, and to unravel, amidst all the warp and woof of the intricate relationships between the English-speaking peoples, those common strands that not only unite us but give us our innermost identity; those things that, beneath all the surface differences, make it unthinkable that we should ever really drift apart.

What are those things? More important, what should they be henceforth?

It does not seem to me enough to say they are Freedom, Democracy, and Equality before the Law, and let it go at that. The world is divided into two opposing camps. They are massed against each other on two separate fronts. On the material front they are building up cataclysmic and terrible defensive forces; each in fear of being outdone by the other. All men pray they will never be used. The other front is that of the will and the mind. There, on that front, the forces are being used all the time.

In the presence of a Prime Minister, of an Ambassador, and so many other leaders in public affairs, I would not dare to say anything about the first front. But our convocation has taken place here, in this movingly beautiful and educational setting. It is with the most prized and precious of all distinctions, the marks of learning, that you have been so gracious to honor us. It is our common belief that education cannot cease with college or university; that, indeed, it never ends. The means of education are many; among them being - potentially - all the devices science has made available to us for spreading information and opinion. I feel I may briefly say something about the other front; it is, in fact, a war - the war of words and ideas.

If you take the words, Freedom, Democracy, and Equality before the Law as some kind of rough highest common factor, then it is by and large true to say that they represent the difference between the free and the unfree world But what do Freedom, Democracy, and Equality before the Law add up to? We may not be willing to contemplate life without any one of them. But even if we put all three together they form a very small part of life. They are no more than a frame for living. What are we going to place inside it? . . .

We talk about the American way of life, the Canadian way of life, the English way of life. Is it not time we stopped using these cliches and examined what they really mean? Remember: we are not talking about our own individual, fortunate, and highly interesting existences, but about the way of life of 239 million people. Is theirs the American way of life, the Canadian way of life, the English way of life? And if it is, are we proud of it? Suppose that, as we are confidently promised, we double its material benefits in a generation, will it even then be a satisfactory existence?

If the Anglo-Canadian-American Community is to have any distinguishing mark of its own, if some Toynbee a thou- sand years hence is to speak well of our joint civilization through its rise, perihelion, and decline, let it be that he shall speak of a civilization that taught all its people to lead a full life.

The fact that this is far from being the case at present is not the fault of the universities, the colleges, or the schools. You have each individual human being for so short a time. The forces against you have him all the rest.

Ninety years ago John Stuart Mill, delivering his inaugural address at the University of St. Andrews, gave education its widest possible definition: "Whatever helps to shape the human being; to make the individual what he is, or hinder him from being what he is not - is part of his education."

I ask you to look at that definition in terms of our adolescent and adult life. Look at it particularly in the light of what Mill went on to say; that all education must comprise three branches - the intellectual, the moral, and the aesthetic.

To some extent these three branches are all to be found in each of our national educational systems. . . . And afterwards? Afterwards, many of the most powerful influences within our communities not only fail to sustain or satisfy whatever appetite towards further education, towards living a full life, we may have had; they seem to make a determined war against it— .

There are two reasons why we should take all the steps we can to change this attitude and the present state of affiairs. It has been said many times that the West will have to find a new philosophy if it is to withstand the drive of communism. What chance there is of that happening, I do not know. It seems to me a tall order. Philosophies cannot be conjured up and had for the asking. But as the war of words and ideas goes on, we shall be forced to take the fight on to new ground. That ground will move away, in the end, from politics and economics. The final battleground will be the mental and spiritual strength of our peoples. . . .

In the long sweep of history none of our nations is likely to be without its triumphs, or to escape setbacks. For greatness, and indeed for survival, we must - being what we are have strength, and wealth, and power. But it is the nation whose people as a whole have come nearest to experiencing the full beauty and grace and wonder of life which will most enrich mankind, and be longest remembered in the end.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

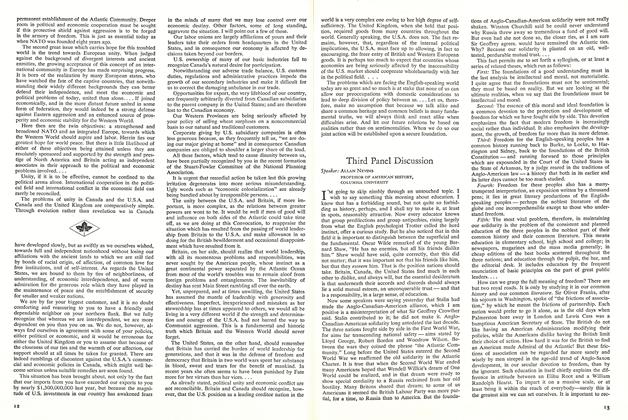

FeatureFirst Panel Discussion

October 1957 By SIR GEOFFREY CROWTHER -

Feature

FeatureOpening; Assembly

October 1957 By THE HONORABLE LEWIS W. DOUGLAS -

Feature

FeatureFinal Assembly

October 1957 By THE HONORABLE JOHN GEORGE DIEFENBAKER -

Feature

FeatureTHE DARTMOUTH CONVOCATION ON GREAT ISSUES IN THE . ANGLO – CANADIAN – AMERICAN COMMUNITY

October 1957 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

FeatureFirst Panel Discussion

October 1957 By CLARENCE B. RANDALL -

Feature

FeatureThird Panel Discussion

October 1957 By ALLAN NEVINS

Features

-

Cover Story

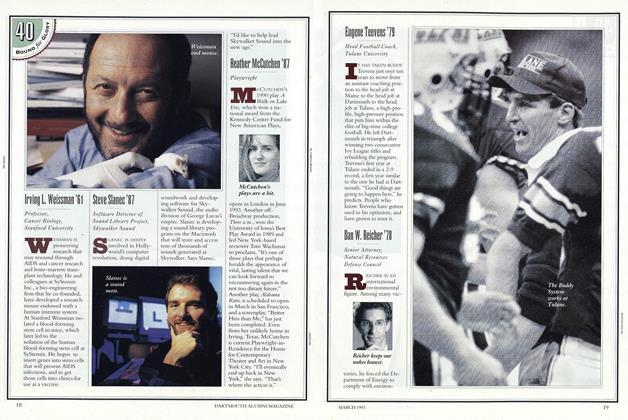

Cover StorySteve Slanec '87

March 1993 -

Feature

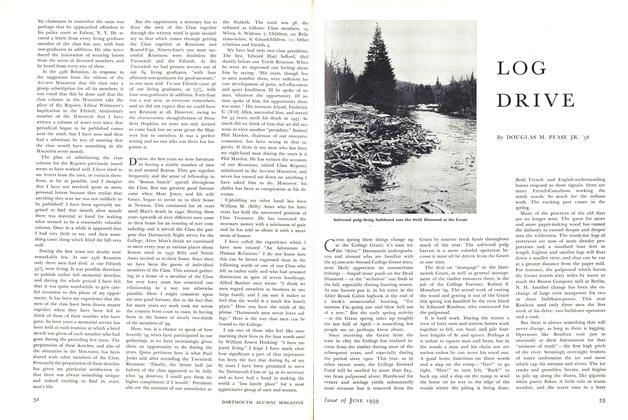

FeatureLOG DRIVE

JUNE 1959 By DOUGLAS M. PEASE JR. '58 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's "New" Curriculum

APRIL 1966 By JOHN HURD '21, PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH EMERITUS -

FEATURE

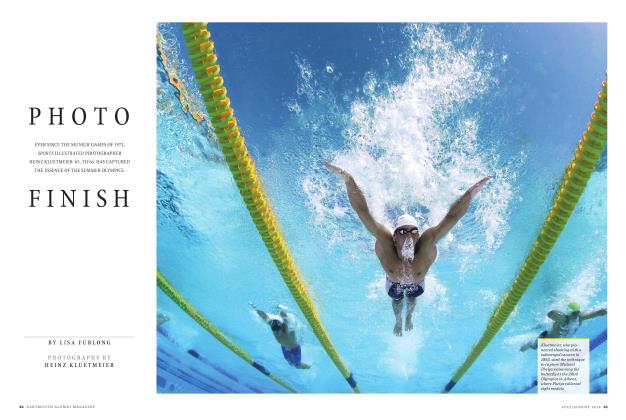

FEATUREPhoto Finish

JULY | AUGUST 2016 By LISA FURLONG -

Feature

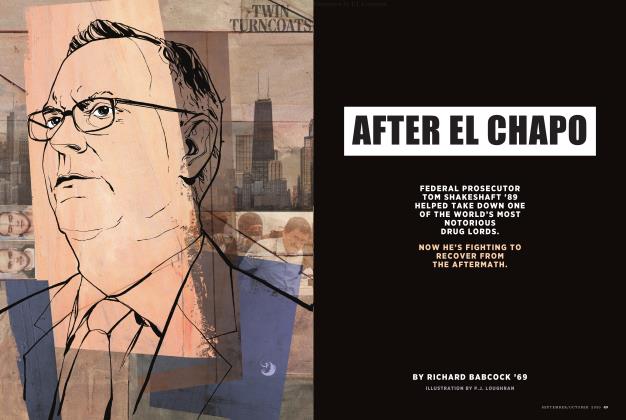

FeatureAfter El Chapo

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2020 By RICHARD BABCOCK ’69 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA 10-STEP PROGRAM FOR GROWING BETTER EARS

Sept/Oct 2001 By ROBERT CHRISTGAU '62, VETERAN ROCK CRITIC