Edited by Lawrance Thompson.New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston,Inc. 1964. 645 pp. $10.

This is a full and representative selection of Robert Frost's letters. Possibly too full: some may think we could dispense with a few of Frost's bickerings and dickerings with collectors of his manuscripts and first editions. But his jealous concern for his rating in the market was characteristic though he knew it had nothing whatever to do with the essence of his poetry. So let's not be captious, for Lawrance Thompson has done a masterly job in editing the letters with scrupulous care, tact, candor, and insight so that they serve, as he suggests, as raw material for the reader's own biography, at least until the official biography upon which the editor has been working for years comes out.

The letters reflect, among other things, Frost's 70-year lover's quarrel with Dartmouth (and other colleges). At Dartmouth briefly in 1892, he was invited back for the first time-by Harold Rugg in 1915, lecturing on "New Sounds in Poetry" in January 1916. He returned often in the 1920's and 1930's, during the early part of this period mainly under the patronage of David and Myrtle Lambuth at Badgery; then in 1943 he was invited for longer visits by President Hopkins and, through the subtle not to say Machiavellian maneuvers of Ray Nash, was lodged in Baker Library as Ticknor Fellow in the Humanities rather than under any private umbrella. The collection of Frostiana which Rugg began was continued by Edward C. Lathem, his successor: it is not surprising that there are more letters in the book from the Dartmouth collection than from any other source; nor that the editor makes generous acknowledgment of Mr. Lathem's help in the preparation of the volume; to him more than to anyone else except President Dickey Frost owed his peculiarly happy relation with this College in his last triumphant years.

If Dartmouth is particularly rich in Frost letters it is in no small part due to the generous gift by Alice Cox of Robert Frost's letters to her husband going back to 1912 and his life in England. Because of the light these letters shed on Frost's complex and subtle character and on the intimate, prickly and tortured friendship between him and Sidney Cox, the friends of both men will follow the course of this relationship through the book with especial interest. They were both men of great sensitivity: tender-minded, in William James's phrase. But Frost had fifteen years more experience of life than Cox so that he emerges as the tough-minded one of the pair. When they first met at Plymouth in 1911 Frost was drawn to the younger man by his awkwardness, naivete, and teasable youth. Cox did some valiant tub-thumping for A Boy's Will and North of Boston in the early days; and Frost was grateful for this. But he pointed out that temperate praise would help him most; and when it came to Sidney's projected book - Walks and Talks with RobertFrost - he called a halt. He would not wear his heart upon his sleeve for Cox or anybody else to peck at: "I can tell you offhand I never chose you as a Boswell."

Sidney Cox told President Hopkins once that he aimed to get hold of the very vitals of his students. This sort of disemboweling process made Frost squirm: in the early days of their friendship he had warned Cox against his propensity to overhaul his own "character too much in the hearing of others." Not that he disapproved Sidney's insistence on honesty, sincerity. But he was suspicious of it; and indeed "sincerity" is a slippery criterion to apply to art and the artist - when is an actor most "sincere," for instance? Integrity seems a safer word.

It got to the point in their relations when Frost was asking Sidney to leave him out of it; there was getting to be too much of him in the classroom, using him to Cox's own hurt. And to his own, he implied: he didn't want to acquire the reputation of Aristides. The insults increase; Sidney winces but comes up for more. Enough of the insults. For Frost was also a true and generous friend. "You're a better teacher than I ever was or will be (now)," he wrote in 1926. And he held Sidney in deep if exasperated affection till the end.

The relationship with Cox reminds us that Frost was a dramatic as well as a lyric poet: his dramatic maskings, as Lawrance Thompson perceptively points out, were protean. One final example out of many will have to suffice.

After Frost's 85th birthday dinner Lionel Trilling was soundly berated for mentioning his "terror"; and rapped on the knuckles for raising the ghost of D. H. Lawrence at the banquet. The reference to Lawrence was not as malapropos as it seemed to many of his hearers. The differences between the two are obvious: "One Jesus is enough," Frost once exploded to Sidney Cox, thus deflating another of Sidney's balloons. The instinct that prompted RF to praise a poem of Lawrence's in an early letter to Edward Garnett was sound. (Nor accidental either, that Garnett should have been one of the early "discoverers" of both.) For they had more in common than a tendency to pulmonary diseases and a strong strain of Puritan didacticism. What they had in common was genius: they are indubitably two of the 20th Century geniuses of our English-speaking race. Both are originals, both are unique — no one could mistake either of them for some one else. And both have that kinesthetic, tactile quality which is the mark of the greatest art. Verbs make the landscape of the very first paragraph of The WhitePeacock come alive; Frost's "Butterfly" (published when he was twenty) is "precipitate in love/Tossed, tangled, whirled and whirled above."

Frost replied to Trilling's hope that he had not been distressed: "Not distressed at all. Just a little taken aback...." Trilling had made the party a surprise party, departed from the Rotarian norm in a Rotarian situation. It is all there: the fresh twist of a subtle mind. And the integrity, the magnanimity.

Professor Emeritus of English

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureVANISHING ABSOLUTES

December 1964 -

Feature

FeatureOur Battle To Reform The Education of Teachers

December 1964 By THOMAS W. BRADEN '40 -

Feature

FeaturePRESIDENT'S POLLSTER

December 1964 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

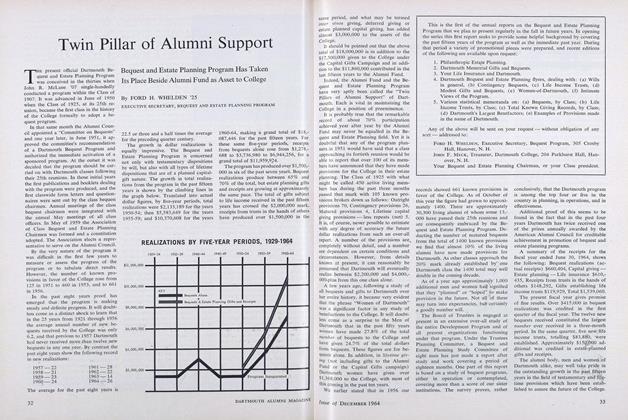

FeatureTwin Pillar of Alumni Support

December 1964 By FORD H. WHELDEN '25 -

Feature

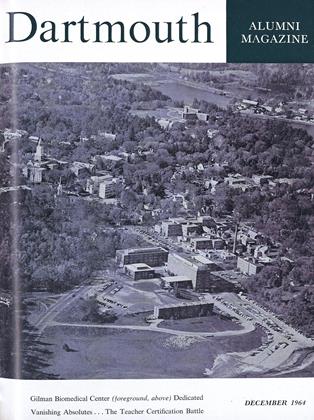

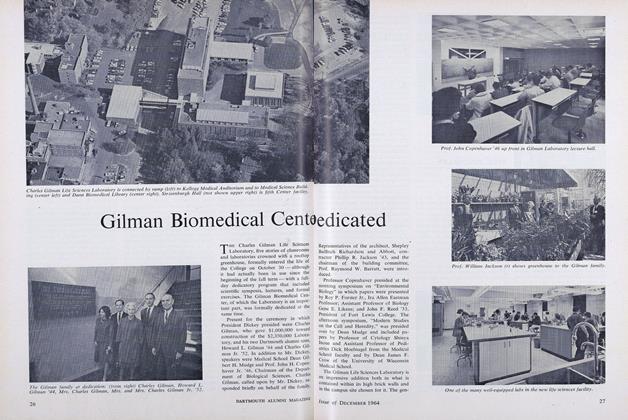

FeatureGilman Biomedical Centedicated

December 1964 -

Article

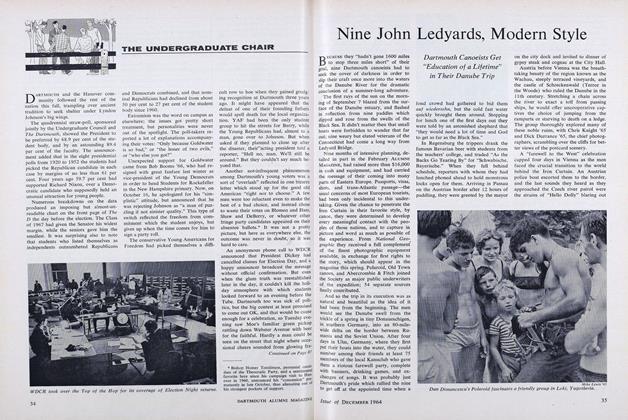

ArticleNine John Ledyards, Modern Style

December 1964 By BOB WILDAU '65

STEARNS MORSE

-

Books

BooksProse Preferences.

NOVEMBER 1927 By Stearns Morse -

Books

BooksTOLSTOY

JANUARY 1929 By Stearns Morse -

Books

BooksTHE AMERICAN NOVEL AND ITS TRADITION.

December 1957 By STEARNS MORSE -

Books

BooksTHE STORY OF MOUNT WASHINGTON.

June 1960 By STEARNS MORSE -

Books

BooksSELECTED PROSE OF ROBERT FROST.

OCTOBER 1966 By STEARNS MORSE -

Books

BooksEmpty Rooms

September 1975 By STEARNS MORSE

Books

-

Books

BooksALUMNI PUBLICATIONS

June 1917 -

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

April, 1922 -

Books

BooksON POETIC IMAGINATION AND REVERIE: SELECTIONS FROM THE WORKS OF GASTON BACHELARD.

DECEMBER 1971 By DONALD OHARA '53 -

Books

BooksTHE MEANING OF CULTURE

MARCH 1930 By H. F. West -

Books

BooksSPIKED BOOTS: SKETCHES OF THE NORTH COUNTRY.

November 1959 By ROBERT S. MONAHAN '29 -

Books

BooksTANSTAAFL: THE ECONOMIC STRATEGY FOR ENVIRONMENTAL CRISIS.

JULY 1971 By THOMAS B. ROOS