Being a careful translation ofthe only known copy of the Gaeomemphionis Cantaliensis Satyricon. By Robert E. Pike '25. Privately printed, 1963.

This limited edition of The Satire of theCantalian Who Scorns the Whole World, although not really the strangest book in the world, is a most unusual volume. Mr. Pike, Chairman of the Languages Department, Monmouth College, has translated a unique manuscript (Z17132) from the National Library in Paris. The text was first published in 1628 with no indication of author, publisher, or place of publication. It is, as Mr. Pike states in his informative Introduction, a livre a clef in which the names of persons and places are disguised under false names; the pseudonyms are derived from Greek and Latin roots (Gaia, world, memphein, to scorn; Hilario, Henri, comte de Bouchage and due de Joyeuse) or anagrams (Ganicius, Ignacius, referring to the Jesuits by the name of their founder, Ignacius Loyola). An excellent key with explanations follows the author's Introduction; when the pseudonym first appears in the text, a footnote usually indicates the person or place implied.

The Satire itself, a Menippean combination of prose and verse, relates the adventures, or rather, misadventures of the Scorner of the World as he traveled from his native Auvergne near Mount Cantal to seek his fortune as a scholar in the cities of Bordeaux (Comhydoria, near the water), Toulouse (Astycrium, capital city), and Paris (Argyroploeum, silver boat). In Bordeaux the Scorner is forced to flee for his life after a beating because of his unappreciated efforts to educate and discipline the son of Alopecius (Jean-Louis de Nogaret, due d'Espernon). On the way to Toulouse he is persuaded to join the company of Ganicius (the Jesuits) but is dissuaded by the sight of the damsels of Toulouse:

Already the kindness of the ladies we passed, and their polished conversation, seemed to me to be somehow more attractive than a whole band of dancing Graces or a host of Cupids. ... I will not fear to confess that the tenderness of my spirit was inclined toward the blandishments of love. The sweet faces of the beautiful girls, the uncovered whiteness of their budding breasts, their foreheads unwrinkled in gentle laughter, erased from my mind, revelling in such delights, the memory of my promised sanctity, and the name of frightful religion. ... Whenever we met a better-shaped one, as if I were adopting a more modest gait, I slowed my steps; and, under the pretext of having to spit, turning my neck to one side, I safely gave her the once-over, (hue illuc curiosum lumen securius diducebam) pp. 81, 83

Gaeomemphio was not successful in joining the Jesuits, but he did join the household of Hilario to gain protection in a lawsuit. According to the narrative our hero was driven out of Toulouse as a result of his success as a scholar. Mr. Pike suggests that "If one finds any mention of this Auvergnat who came to Toulouse and started to run a school in competition with the Jesuits, and was driven out for having composed a book against them, between 1600 and 1615, then one will have learned the name of the man who wrote the Satyricon."

On the way from Toulouse to Paris, Gaeomemphio receives an intriguing account from a frank fellow traveller concerning the rise and fall of the power of the Pope (Stephanotrios, crowned) and the Porphyrii .(Reds, College of Cardinals). Upon arriving in Paris, the Scorner prays at the altar of the goddess of Felicity, the cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris. Two adventures occur as a result. He is refused admittance, actually thrown out of the house of Melanius (Cocini, Marquis d'Ancre), the second in power to Louis XIII, king of France. Secondly, he forms a successful liaison with a noble lady whom he learns is a vampire, a siren who slays her paramours. To avoid death at her hands, Gaeomemphio leaves Paris with all speed and returns to: the happy fields of Cantalia, feeling as did Penelope's husband when, after escaping the cruelty of the Saestrigonians and the potions of Circe, he again entered his home, perched like a nest amid the crags of Ithaca.

Thus ends the tale of the Scorner of the World. The final portion was quoted to indicate the prevalence of literary allusions to Greek and Latin literature. This edition will be of value to the scholar since Mr. Pike presents the Latin text on the left page and the translation on the right. The editor states that "the Latin our author used is devilishly difficult." This reviewer must agree. This translation reveals the editor's mastery of the Latin text and his skill in rendering it into understandable, readable English.

The picture of the early 17th Century disclosed in this volume, its social customs, political figures, religious thought and practice, should make it useful to the scholar; however, it also should be of general interest to the educated, inquisitive person who desires to read a personal, satiric, intriguing account of one man's life and travels in an age and circumstances far removed from our own.

Assistant Professor of Classics

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

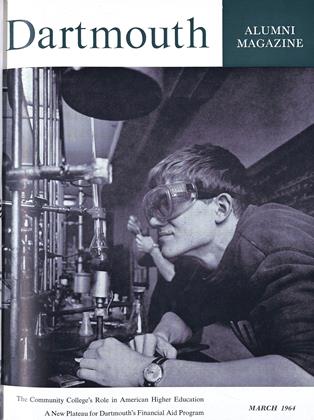

FeatureTHE COMMUNITY COLLEGE

March 1964 By THOMAS E. O'CONNELL '50 -

Feature

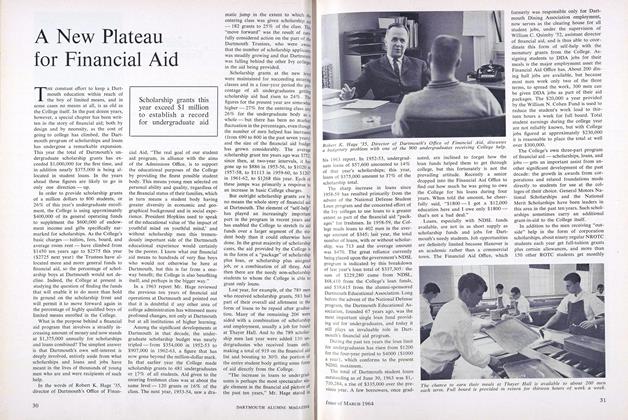

FeatureA New Plateau for Financial Aid

March 1964 -

Feature

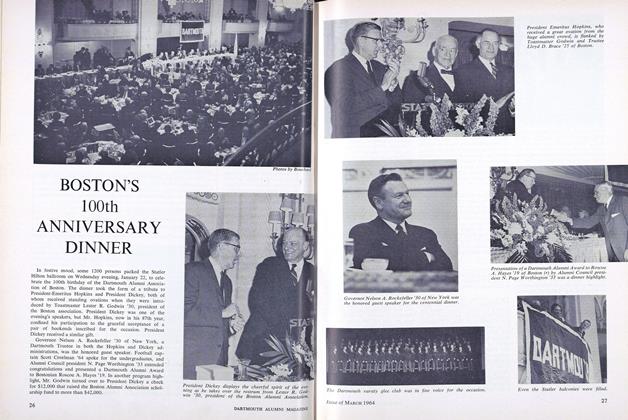

FeatureBOSTON'S 100th ANNIVERSARY DINNER

March 1964 -

Article

ArticleA graduate of 1804 who stood up for an American Culture

March 1964 By BEN HARRIS McCLARY -

Article

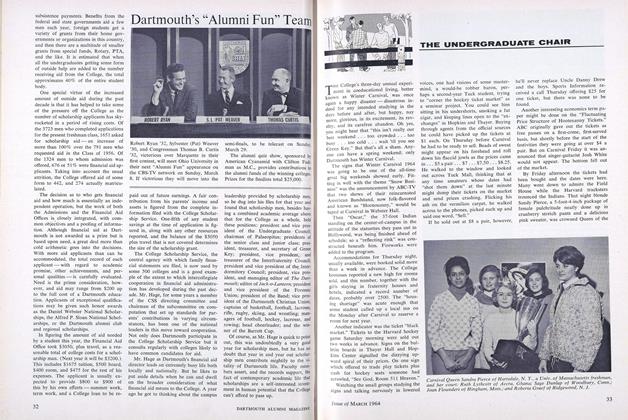

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

March 1964 By DAVE BOLDT '63 -

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

March 1964 By GEORGE O'CONNELL

Books

-

Books

BooksAntic Brew

April 1979 By CHARLES E. WIDMAYER '30 -

Books

BooksSpiritus Loci

February, 1931 By Eric P. Kelly -

Books

BooksGOVERNMENT IN AMERICA.

February 1958 By HERBERT GARFINKEL -

Books

BooksCrumps

December 1917 By K. A. R. -

Books

BooksNOT FAR FROM THE RIVER.

FEBRUARY 1968 By MURRAY SYLVESTER -

Books

BooksOUT OF THIS WORLD,

January 1951 By NATHANIEL L. GOODRICH