David Brion Davis has written another superb account about mankind's most peculiar institution, human slavery. In his earlief Pulitzer Prize-winning book, The Problem of Slavery inWestern Culture, Davis meticulously traced the diverse nuances of slavery from antiquity and Renaissance Europe to Latin America and England's North American colonies. One basic lesson appeared throughout this study: slavery must be understood in terms of Western man's desire to excell and advance materially through slavery despite contradictory demands for democratic institutions and quests for freedom.

Davis again uses comparative history in this volume to provide readers with the necessary balance and understanding of slavery during one of the most volatile and introspective periods of western civilization, the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Complexities and persistent contradictions inherent in Great Britain, France, and America, nations confronted with the "Problem of Slavery," offer an immense challenge to objective scholarship. Davis handles these scholarly obstacles with ease. After defining his terms and providing the reader with an important chronology of events, he delves into philosophical, religious, legal, political, and economic questions, producing a masterpiece in historical research.

Although the contradiction of slavery had from ancient times given "rise to conflict, fear, and accommodations," Davis contends that troubled consciences reached a state ap- proaching paranoia during the age of Revolution. Political, economic, and philosophical issues evolving from rhetoric derived from the American and French Revolutions provided that additional impetus for serious debates over the merits of slavery. A confusing aspect of western civilization emerges, but Davis's lucid interpretations clarify these troubled times.

First, he prepares the reader for difficulties French, English, and American abolitionists encountered as warfare impinged on the security of slaveholding societies. He then discusses in great detail the fate of anti-slavery as it rested in legislative assemblies - the British Parliament, the French Constituent and Legislative Assemblies, and the Constitutional Convention and Congress of the United States. Governments of these dominant nations, however, acted cautiously. To avoid dissension they styled themselves as temples of liberty while simultaneously reassuring slaveholders that slavery would continue unabated. Each nation offered also a unique response to the peculiar institution.

In chapters four through seven ("The Boundaries of Idealism," "The Quaker Ethic and the Antislavery International," "The Emancipation of America I," and "The Emancipation of America II"), Davis conveys the most important message in his study. While the French and British often vacillated between favorable and intolerable extremes, Americans seemed most agitated by the problem of slavery because of the young nation's dependency on human bondage and the large numbers of blacks domiciled within the United States. Jefferson personified the American dilemma best, noting: "We have a wolf by the ears, and we can neither hold him, nor safely let him go. Justice is in one scale, and self-preservation in the other." The trials and tribulations of international abolition proved astounding. Liberal ideology popular during the age suggested that slavery be eradicated, but only the United States had to contend with the dual problems of economic ruin and potential racial warfare. Davis observes that the British and French were inclined to recognize black humanity with far greater frequency than Americans. United States thinkers, conversely, accepted internal debate and sanctioned antislavery societies particularly in the slaveholding South. A clear delineation therefore appears between the philosophical views of Europeans who perceived the dilemma more in the context of abstract moralism and the more pragmatic approach of Americans who grappled with philosophical and social issues.

Davis's use of comparative history enables him to be far more convincing in his understanding of United States slavery than Carl Degler who opted for United States as opposed to Brazilian slavery in his prize-winning NeitherBlack nor White. Far more than the English or French, Davis shows that Americans "understood the . . . painful complexities of converting domestic servants into free men." But perhaps the most profound message contained in Slaveryin the Age of Revolution appears through the recognition that historians "too often underestimated the economic strength of slavery during the Revolutionary period, exaggerated the force of antislavery sentiment..., and minimized the obstacles that abolitionists faced...."

This convincing volume places the pathology of United States and European slavery in a broad context. David Brion Davis's erudite and extremely well-written book offers readers a better understanding of the implications of slavery in western democracies.

THE PROBLEM OF SLA VERYIN THE A GE OFREVOLUTION, 1770-1823By David Brion Davis '50Cornell, 1975. 576 pp.Cloth, $17.50; paper, $5.95.

Professor Nelson of Dartmouth's historydepartment teaches courses on Black America.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureSelf-Evident Truths

May 1976 By ARTHUR M. WILSON -

Feature

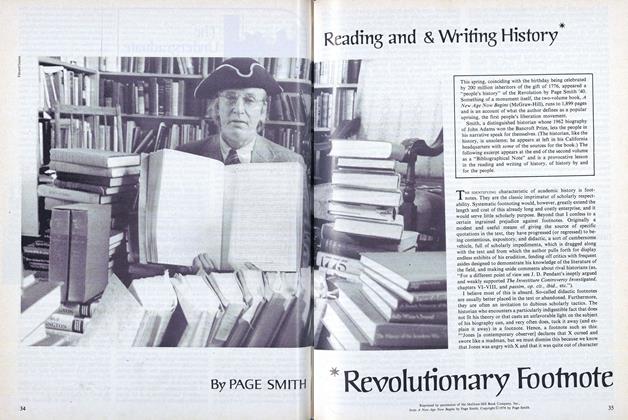

FeatureReading and Writing History and Revolutionary Footnote

May 1976 By PAGE SMITH -

Feature

FeatureWhen Dartmouth Had Its Own State (Almost)

May 1976 By JAMES L. FARLEY -

Feature

FeatureThanks to Daniel Oliver, A Gathering of Lovers

May 1976 By DAN NELSON '75 -

Article

ArticleThe Green: A House Mover and an ex-President Proved Who Owns It (Didn't They?)

May 1976 By Jabberwocky, Lewis Carroll, JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

May 1976 By WALTER C. DODGE, CHARLES J. ZIMMERMAN

Books

-

Books

BooksFaculty Authors

November 1944 -

Books

BooksMARKETING RESEARCH.

November 1952 By Albert W. Frey '20 -

Books

BooksCYCLES: The Science of Prediction

June 1947 By Bruce Knight -

Books

BooksCONTRABAND

June 1936 By Henry M. Dargan -

Books

BooksITALIAN ODYSSEY, AN EAR TO THE WIND.

OCTOBER 1969 By PENNINGTON HAILE '24 -

Books

BooksASPECTS OF CRITICISM, LITERARY STUDY IN PRESENT-DAY GERMANY.

JANUARY 1969 By STEPHEN G. NICHOLS JR. '58