The Wheelock Dream, Sparsely Realized, Is Still a Force in the Life of the College

OCTOBER 1965 JOHN HURD '21The Wheelock Dream, Sparsely Realized, Is Still a Force in the Life of the College JOHN HURD '21 OCTOBER 1965

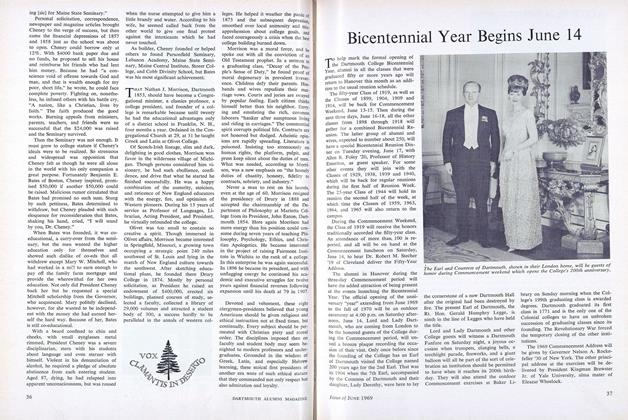

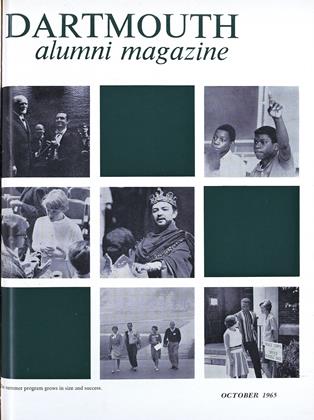

Three entering freshmen of Indian lineage underscore the historic tradition in which Dartmouth takes pride

AMONG the 800 boys arriving on campus this fall to constitute the Class of 1969 are three freshmen of Indian lineage. Their' acceptance, fresh affirmation of Dartmouth's abiding faith in its original mission, is a reminder that the facile and amusing Indian symbolism garnishing the present-day College really stands for something and that the football cheers and cheerleaders, the College songs and souvenirs, and the place names are the mementos of an ideal which burned so hotly in one man's heart and head two centuries ago that he wrested a clearing from the wilderness to establish a new frontier of hope. Few colleges have a more meaningful motto.

But Wheelock's dream has often seemed scarcely more, than a dream. His aboriginal scholars were few, scattered, and unpredictable. Bitterly he wrote:

None know, nor can any, without Experience, Well conceive of, the Difficulty of Educating an Indian. They' would soon kill themselves with Eating and Sloth, if constant care were not exercised for them - at least the first year. They are used to set upon the Ground, and it is as natural for them as a seat to our Children - they are not wont to have any Cloaths but what they wear, nor will they, without much Pains, be brot to take Care of Any, - They are used to a Sordid Manner of Dress and love it as well as our Children to be clean. They are not used to any Regular Government, the sad Consequences of which you may a little guess at. They are used to live from Hand to Mouth (so we Speak) and have no care for Futurity. . . .

Wheelock never lost hope, however, or stopped trying, and in 1733 he sent Levi Frisbee and two others into the Canadian forests to seek suitable candidates for his school. In three weeks Frisbee's party found four.

In the years that followed, Indians at Dartmouth were chiefly shadows in the woods. In the past hundred years, the College enrolled only 28. From 1865 to 1900, only two were graduated. From 1900 to 1965, 23 attended, seven of whom were graduated. The total number of graduates in a hundred years is nine.

The search continues, and far more intensively, for Dean Charles F. Dey, who enrolled one Indian in the 1964 ABC Summer Program and six in the 1965, and for Edward T. Chamberlain Jr., the Director of Admissions, who has enrolled three in the freshman class.

Indians do not automatically receive free tuition at Dartmouth. If they need help, they must apply for scholarship aid, but, once qualified, they are treated more considerately than was Robert Hawthorne of the Class of 1874. In a passionate four-page letter, written from home in Kansas in August 1873 just before college opened, he begged President Smith to reconsider his refusal to grant him additional scholarship aid. Hawthorne lacked only his senior year to complete his requirements for a degree. He explained that he had sold his cattle in Kansas, worth $2,000, to pay for his education and that he was now destitute and utterly discouraged about his future.

Professor W. T. Gage, in whose house Hawthorne had lived, supported his plea by also writing to the President: "Something can and ought to be done. Dart- mouth College certainly can fulfil its pledge to this young man who has given up all the savings of his whole life to obtain a preparatory education because he was offered at Dartmouth a course of study ... To interrupt him now is a positive wrong and must, and certainly can, be remedied. Pardon my earnestness if I seem to speak warmly, but I as an Alumnus feel that I have actually pledged the honor of this Institution to him." The money was somehow authorized, and Hawthorne was graduated.

Although nothing is known of Hawthorne's subsequent life, the College has followed with pride that of Ohiyesa or Charles A. Eastman, 1887, a Sioux. Beginning life in a buffalo-hide tepee in Minnesota, he went on to acquire, in addition to his Dartmouth BA., the degrees of Doctor of Medicine from Boston University and Bachelor of Laws from Columbia.

When Ohiyesa was four - the name means "The Unconquered" or "The Invincible" - his tribe was decimated in the Minnesota Massacre of 1862, and the survivors driven off into Canada, among them most of the child's family. An uncle, Mysterious Medicine, reared the orphan in all the lore and Spartan self-discipline for which the tribe was renowned. The boy learned to deny himself self food, water, and sleep for long periods, maneuver the trackless forests by night, obtain food from unlikely sources, and defend himself from four-legged marauders as well as two-legged ones.

He came to Dartmouth as an unknown freshman athlete of 25 and startled the College by winning the two-mile run against the best track man, a senior. Ohiyesa's powerful and unorthodox style belonged more to the forest than the cinder path.

In 1883 Matthew Arnold lectured at Dartmouth and was the guest of honor at an ensuing reception. Told that Dartmouth had been founded for the education of Indians, he expressed interest and said that he had never met an Indian and would like to. Ohiyesa was presented, handsome, correct, formal, in full evening dress, including white gloves. Present also at the occasion, the correspondent for the Boston Evening Transcript reported that it could only be guessed what England's great man was thinking or had expected. Completely nonplussed by the poised young man before him, he blushed and stammered, quite at a loss for words. "Ah! eh! ah!" he said, holding out his hand, "You were there - you were there. How did you like it?" (meaning his lecture). With much private amusement the reporter was reminded that Arnold had previously expressed doubt in his writing whether the education of Indians was practical.

When Eastman was 33, he took the post of physician at Pine Ridge Agency, S. D., for a salary of $1200 a year and arrived there with his bride, Elaine Goodale. Aged 28, white, a New England poetess, she spoke fluent Sioux and taught in Indian schools.

Ohiyesa could not always live up to the meaning of his name. In a bitter controversy Captain J. L. Brown, Acting Indian Agent at Pine Ridge, charged Dr. Eastman with insubordination and attempts to undermine Brown's authority with the Indians. The physician countered by accusing the agent of tyranny, lack of cooperation, and incompetence. John W. Noble, Secretary of the Interior, after examining the evidence, upheld Brown and declared that for the good of the Service Eastman should be suspended from Pine Ridge. If he could not be assigned to another place within 15 days, he must resign or be fired. He resigned.

The setback was temporary. Dr. Eastman enjoyed a long and distinguished career in this country and in Europe as scholar, lecturer, and author of several books on Indian life and history. A major accomplishment was the revision of land laws to protect Indians in the transmission of their property. At the request of President Theodore Roosevelt, he gave to some 30,000 Indians surnames in English which retained the meaning of their original names. Thus, Bob-Tailed Coyote became Robert Taylor Wolf. A sightless Indian called Can't See With His Eyes became John Blind. Tateyonake waste win. She Who Has a Beautiful Home, became Goodhouse. When the Indian name was not too long, Dr. Eastman retained it, e.g. Matoska meaning White Bear.

When the Class of 1887 held its reunions in Hanover, Dr. Eastman discarded conventional dress and led processions in full Indian regalia. During Lord Dartmouth's visit to Hanover in 19,04, he played the role of Samson Occom in a tableau.

Eastman would have considered his death at the age of 80 as premature. He was quoted in an English newspaper as saying that Sioux Indians die at an average age of 90 and that some live to be 125. At 70 he considered himself in top physical shape. He ascribed Sioux longevity to traditional habits inculcated by teachers from the accumulated wisdom of centuries. Dr. Eastman's grandmother used to roll him in snow, lay him on ice, and plunge him in hot oil to harden him to a life where physical endurance in climatic extremes is part of an essential code.

Of the five New England Indians accepted by the College, one has played an important role in Maine history. Born on the Penobscot Reservation, Horace A. Nelson '04 returned home after his freshman year to manufacture canoes and serve as governor of his tribe. In 1959 it numbered only 551 persons who retained many of their customs. They lived, however, in houses like their white neighbors and enjoyed traveling by automobile more than canoe. Governor Nelson himself set the tone in the Francis Place, a large two-story house with mansard roof and dormer windows.

Nelson's administration saw civilization encroach steadily on tribal simplicity. Paths became sidewalks, and trails turned into roads. Indian health improved with the decontamination of wells, and a sewage system was built under white supervision. Eventually the Reservation boasted a park and recreation area, historical markers, and a birchbark village for the titillation of white tourists.

Dartmouth's greatest Indian athlete is John Tortes '09, a sensation in big-league baseball where he was known as Chief Meyers. He entered the freshman class as a brilliant prospect for the football team because he was fast, tough, and strong. Ralph Glaze '06, in Albuquerque, had been impressed with the catching ability, batting average, and competitiveness of the young Indian playing baseball. When he was struck by a wild pitch, the ball bounced almost to the pitcher's mound. Instead of falling unconscious, Tortes brushed off the impact as a lesser man might a fly. Obviously here was first-class Dartmouth football material.

Though he had never played football, he tried out for, the team, and the coach instructed him in the fundamentals. "Jack," he said succinctly, "you charge through that line, jump the man with the ball, throw him, and keep him down." "The man" happened to be.good varsity material; he was C. Arthur Fifer '08, known as "Pot." Jack, weighing 200 pounds, charged, jumped, and threw him to the ground, and kept him down by grinding a shoulder into him. Not only did poor Pot pass out; he was passe for the rest of the season. Admiring Jack's strength more than his finesse, the coaches decided to reserve him for knocking out replaceable baseballs.

Before the baseball season, however, Jack found himself in serious academic difficulties which led the college authorities to scrutinize his scholastic record. They discovered that his high-school credits and diploma were bogus. He had gone no farther than the fourth grade. Glaze and other excessively zealous Dartmouth men had persuaded a compliant high-school boy to relinquish his diploma to Tortes. Called upon to act, President Tucker, confronting Tortes with the falsified certificate, is said to have observed, "It is written here that this highschool graduate is five feet six and has red hair." Then, turning to the blackhaired, 200-pound, six-foot Indian, he asked, "Does this description fit you?" Impressed with the President's perception and wisdom, the erstwhile freshman subsequently remarked, "Dr. Tucker with the eye of an eagle looks like a tree full of owls."

Tortes was always grateful for his Dartmouth experience; it paved his way to the big leagues during the era of Babe Ruth, the vitriolic McGraw, the effervescent Casey Stengel playing center field for Brooklyn, and Christy Mathewson whose supreme pitching Chief Meyers caught. He has the peculiar distinction of playing in three world series for the New York Giants and, surprisingly enough, in one for the Brooklyn Dodgers. In 122 games he had a fielding average of .937 and batted .385. In 1917 he was named to the Grand National All-American Baseball Team, covering 47 years, from 1871 when professional baseball started. Sports writers are agreed that only the ten-year rule prevented him from being named to Baseball's Hall of Fame.

Now nearly 86, Chief Meyers in California likes to comment on the good old days. "Big league ball players don't hit like they used to," he says. "They all grab on to a thin-handled bat, and they go for home runs. So they strike out more. Even a great hitter like Mantle will fan 100 times a season. I never struck out more than three times a season." Nor is the Chief pleased with bunters. "Lots of times they bunt at the wrong time. Or they send the wrong man up. When I was playing with Mr. McGraw, we always sent up the man to do what he could do best."

Victor Johnson '10, a full-blooded Indian from the State of Washington, devoted his career of 30-odd years to education. A quiet, deeply sensitive student, he wrote poems about Nature in which he saw Nature's God, and one of these was published by the Dartmouth Magazine in his sophomore year. Interrupted by a five-year break as a superintendent in Hawaii, he spent his professional life in the Indian Service as Supervisor of Indian Education for the Pacific Northwest. Now retired, he lives in Bellingham. Washington, where he raises a few cattle and chickens, digs clams, and during the summer and fall runs a fish trap.

Teacher, farmer and rancher, David Hogan Markham '15, a Cherokee, took post-graduate work at the University of Chicago and at the University of Arizona. As a teacher interested in visual education and physics in Oklahoma, Arizona, and Arkansas, he described himself in 1947, however, as a "soils man with the USDA-SCS" because his job took him into the field where he got "lots of mother earth" on him. In 1947 he was appointed Director of Conservation and Reforestation . for the Republic of El Salvador for two years in an American attempt to improve the standard of living among Central and South American countries. After 1954 he occupied himself with pipe-line companies in Kansas, Missouri, Oklahoma, and Texas, and settied claims concerning damages and rights-of-way. In 1961 he retired to Tahlequah, Okla., and 33 acres of orchard and pasture land.

Though the Indian yell for the team is always with us, its originator, Simon Ralph Walkingstick '18, who had some reciprocal yelling help from Markham, was lost for many years. As late as 1959 his daughter called at the Dartmouth Alumni Records Office in Hanover to inquire if her father were still alive. In 1962 he made clear that he was. In a letter to the DARTMOUTH ALUMNI MAGAZINE, he regretted his carelessness about subscriptions, announced his retirement from the oil business in Oklahoma, and gave his address as Cape May Point, N. J., where he hoped to see more of his children and Dartmouth men. In college Chief Walkingstick was so close a friend of his classmate, Dr. Rolf C. Syvertsen, later Dean of the Dartmouth Medical School, that he named his son Rolf Syvertsen Walkingstick. The son was killed in the war against Japan.

The Reverend F. Philip Frazier '20 combined the best traditions of the Sioux and Dartmouth College. A proud race with an illustrious heritage, the Sioux, originally numbering about 30,000 under such chiefs as Red Cloud, Little Crow, Spotted Tail, Crazy Horse, and Sitting Bull, bitterly resisted white encroachment. Most historians have lauded them for their courage, horsemanship, and high ethical standards.

Dr. Frazier had a long Christian tradition. His grandfather, the first ordained minister among the Sioux, served them for more than 30 years. The son, also a minister, served 35 years, and the grandson, yet another 40. Born in a tepee, he knew scant English before entering school. From his older brother he had picked up a few slang expressions like "You bet your boots!" After Santee Normal Training School in Nebraska, he attended Yankton College Academy for four years and Mt. Hermon for two. In 1916 the war interrupted his Dartmouth education, and he spent thirteen months in France and Germany. Mustered out, he attended Oberlin College from which he was graduated in 1922. From there, he entered the Chicago Theological Seminary.

His guiding purpose was to help his people utilize their resources, particularly land. The state with its omnipresent and omnipotent control over a segregated people had carried on spurious missionary work by giving them shoddy goods and debilitating financial handouts. Dr. Frazier believed that they could become independent by adopting a responsible Christianity. The immediate needs were scholarships for high schools and junior colleges as stepping stones to the universities. Once educated to dignity and selfrespect, they could then compete in a white man's world.

He became businessman as well as pastor. On Standing Rock Reservation in North and South Dakota with its 958,500 acres and 3,057 Indians in the 1950's, only 40% of the heads of families were considered capable of full employment. Most lived in one-room log houses with an average of 2.5 persons a room, and 19% had eight persons in the home. 90% had no running water. Only 22% utilized their land. The average yearly income was $650. 40% had income from wages, 33% only from welfare, and 70 families with no income lived with relatives and friends. Tuberculosis, measles, pneumonia, and infant mortality were rampant, and the accident rate very high.

At Dartmouth's 1964 Commencement, Dr. Frazier received an honorary degree from President Dickey, who said, "We cannot here sense the deprivation of dignity, mind, and spirit in your people today without realizing how tragically unfulfilled is Wheelock's purpose to educate the Indians."

Considered the most civilized of all North American Indians, the Cherokees, formerly owners of large tracts of land on both sides of the Appalachians and skilled and prosperous farmers, have sent more students to Hanover than any other tribe. The most distinguished is Frell MacDonald Owl '27. As Superintendent of the Red Lake Reservation in Minnesota, he and a staff of 50 guided 3,000 Chippewas, administered 500,000 acres of land, a sawmill, a commercial fishery producing 1,500,000 pounds per year, and an annual fair exhibiting tribal arts and crafts. Later, on another reservation of 585,000 acres at Fort Hall, Idaho, he administered tribal law for 2600 Shoshones and Bannocks, neither of whose language was familiar to him. He supervised a phosphate mine worth $50,000 a year, 7,000 head of cattle, 47,000 acres under irrigation, the education of 650 illiterates, and the disposition of buffalo and elk carcasses when herds in the national parks were reduced.

Lawyer, businessman, and educator, he ceaselessly advised his people in all the complex problems of their assimilation into the white man's culture. Now retired from the Department of the Interior where he was Advisory Architect for Indian Camp Grounds, Owl, president of the Lions Club of Cherokee, N. C., has built there Pine Grove Camp, a recreation area accommodating vacationers with tents and trailers.

Departing from the predominantly public service interest of his predecessors, Benedict E. Hardman '31 enriched his college experience with a musical avocation. A first-rate saxophonist and bass clarinetist, he was leader of the Dartmouth College Band and a member of the Players Orchestra and the Instrumental Club. During his summer vacations he directed dance orchestras in Europe. After graduation he went to work for the American Broadcasting System, and later for the Columbia Broadcasting System he wrote his own news analyses and broadcasts. He has taught radio writing and announcing in Minneapolis.

Two other Indians loom large in the history of Dartmouth athletics. Roland B. Sundown '32, known as Rolando or Sunny, used to appear at football games in full Indian dress. An English major, after graduation he attended six universities for graduate work, taught in a number of schools, served as an Army private, was an accountant for an oil company, and clerked at an Army airfield. Harold P. Hinman '10 provided him with sufficient money to enable him to re-enter graduate school, work for his Master's degree, and specialize in American Indians in literature. Called to New Mexico this year because of a family emergency, he took a temporary job in the New Mexico Union Building at the University but expects to teach again.

Son of the Chief of the Mohawk Tribe on the St. Regis Reservation, New York; Everett E. White '37, captain of the freshman track team, led his runners to victory in two of their three meets and broke the cross-country course record at the University of Vermont. A major in Economics, White spent some time in Greece administering economic aid on behalf of the U. S. Government. Later he served with the Indian Affairs Division of the U. S. Department of the Interior and worked on Indian problems in New Mexico. He is at present a program analyst in the Public Health Service in Washington.

A second Maine Indian, the son of Chief Henry Red Eagle, a guide and woodsman, is Henry Perley Eagle '43, who has changed his name to Henry Gabriel Perley. As an undergraduate he achieved unusual success: vice president of Phi Sigma Epsilon, president of the Sword Club, captain of the fencing team, a member of lunto, an English honors man, a graduate cum laude. He attended graduate school at Boston University, the University of Maine, and the University of Cincinnati. Before going into business, he was instructor in English at Worcester Polytechnic Institute and chairman of the Department of English at the Fairfield High School in Maine.

The last Indian to attend Dartmouth and one of the most colorful was Chief Flying Cloud '49, whose Anglicized name was William John Cook, or Bill for short. Born during a storm, which by Indian custom suggested his name, he was brought up on the St. Regis Mohawk Indian Reservation, Akwesasne, which means Where the Partridge Drums, on the St. Lawrence River.

To the campus he brought his wife, Wari Kawennaien, Princess Echo, born and reared on the Kanawke Reservation, also on the St. Lawrence. They had been married at Cherry Point, N. C., when Flying Cloud was completing his flight training. Flying a Hellcat for 40 months as a Marine pilot in the South Pacific and the Philippines, he won the Purple Heart, two Distinguished Flying Crosses, six air medals and three campaign stars.

The war concluded, he and Princess Echo returned to Hanover where as a sophomore he resumed his education. Here was born to them in 1947 a boy whom they named Ronwi Kanawaienton, which means Beware of Seemingly Firm Ground Made Treacherous by Spring Freshets, but his American name is easier: Thomas Louis Cook. In the Dartmouth College Archives is a certificate signed by John Sloan Dickey, "Grand Sachem," reading:

E COLLIBUS CLAM ARE VOXAUDITUR

[A new voice is heard crying from the hills] Know all men by these presents that

RONWI KANAWAIENTON

A free-born child of this reservation is hereby extended the welcome of all the Dartmouth tribe.

April 23, 1947

In his junior year, Flying Cloud used to carry his baby on a papoose board, modeled after one in the Dartmouth College Museum. While her husband buried himself in his books, Princess Echo helped finance his education by opening an Indian crafts shop named Akwesasne on College Street where she sold Iroquois lacrosse sticks, moccasins, snowshoes, Adirondack pack blankets, and trinkets made of beads, leather, and birchbark and fashioned on the Mohawk, Chippewa, Huron, and Abenaki Reservations.

A lecturer on Indian culture after graduation, Flying Cloud in one year visited 63 camps from Maine to Pennsylvania and traveled 13,000 miles to instruct some 23,000 campers. Assisted by Indian boys, among them his brother Clear Sky (Jake), Poling Fire (Steven), and Burning Sky (also called Jake), Flying Cloud tried to eradicate the image of his people as only painted and war-whooping savages. In costume he would demonstrate hunting, hawk, eagle, and corn dances and talk about Indian history, law, and legends.

Recalled in 1952 to active service as a Captain in the Marine Corps, Bill Cook was killed at Cherry Point when his twin-engine Tigercat on a night flight crashed and burned. Although pulled from the wreckage alive, he died in the hospital. Princess Echo succumbed later to a common Indian disease, tuberculosis. Their son, now 18 years old, applied for admission to the Class of 1969, but, inadequately prepared, he withdrew.

In President Dickey's home are the Wheelock Narratives - nine volumes in which the first President recorded his intentions and experience in educating Indians. He knew himself ordained of God to redeem the Indian from such aboriginal ignorance as scourged the Continent. He wrote in 1771, "The site for Dartmouth College was not determined by any private interest, or to favor any party on earth, but the Redeemer's." Since religion is education, and education today has become a religion, it may well be argued that the lives of Dartmouth's Indian sons validate a two-fold purpose: Wheelock's dream, and the College's latter-day commitment to that dream. "Purpose," John Dickey wrote, "is the fundamental continuity of any living thing."

After a hiatus of fifteen years, Dartmouth again welcomes its opportunity in adding the names of William Petzoldt Yellowtail Jr., Brian Gordon Maracle, and Gregory Dale Turgeon to its roll.

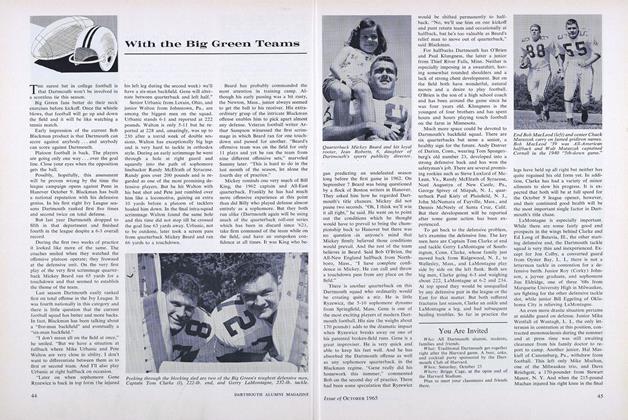

Bill Yellowtail '69 of Wyola, Montana,one of the three freshmen of Indian lineage, the first enrolled in twenty years.

The originator of Dartmouth's Indianyell was Ralph Walkingstick '18, shownhere as a student member of the D.O.C.

Ohiyesa, a Sioux who became the celebrated Dr. Charles A. Eastman '87, as heappeared when he was an undergraduate.

Frell Owl '27, shown at his Pine GroveCamp in Cherokee, N. C., was Superintendent of Red Lake Reservation, Minn.

The Rev. F. Philip Frazier '20, humaneleader among the Sioux, was honored byDartmouth with the D.D. degree in 1964.

Roland Sundown '32 in the war bonnet inwhich he paraded with the College Band.

A special effort to enroll Indian boys in Dartmouth's 1965 ABC program resulted inthe attendance this past summer of (l to r) Ernest Robinson, Gordon Real Bird,Cleveland Burnette, Bruce Glenn, Howard Bad Hand, and Bruce Oakes.

Bill Cook '49 (Chief Flying Cloud of the Mohawks), his wife Wari Kawennaien,and their infant son, Ronwi Kanawaienton, born in Hanover in 1947. Cook,a Marine pilot in the Pacific, later died in a plane crash in Cherry Point, N. C.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Good Summer Press

October 1965 -

Feature

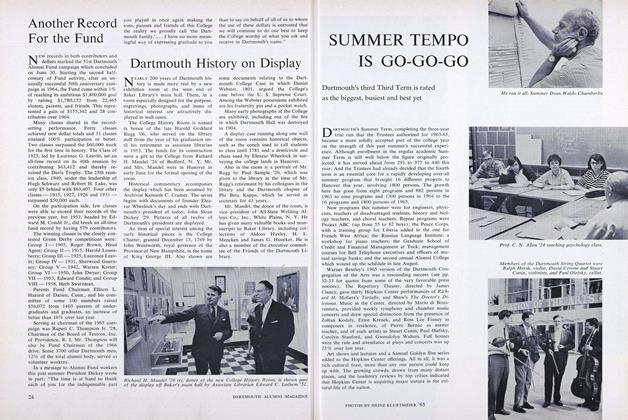

FeatureSUMMER TEMPO IS GO-GO-GO

October 1965 -

Feature

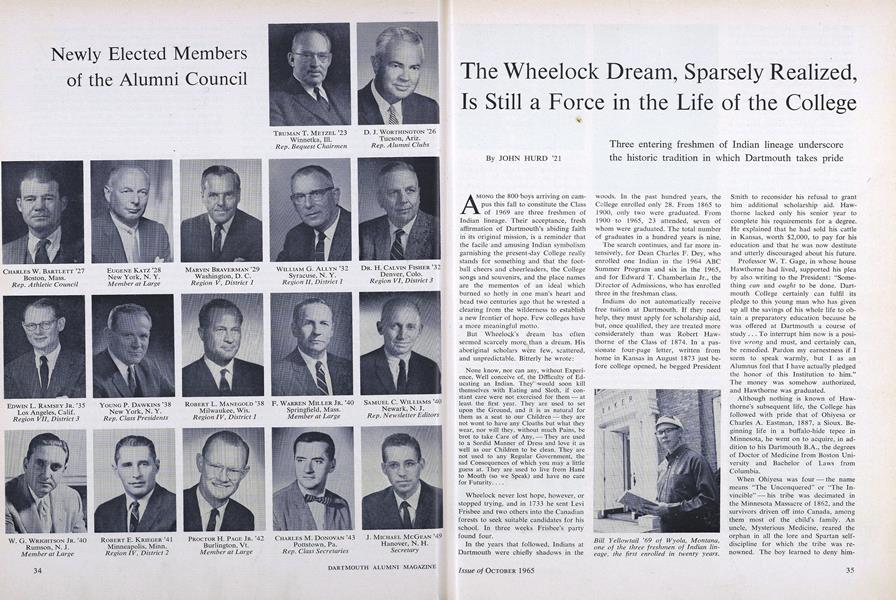

FeatureNewly Elected Members of the Alumni Council

October 1965 -

Article

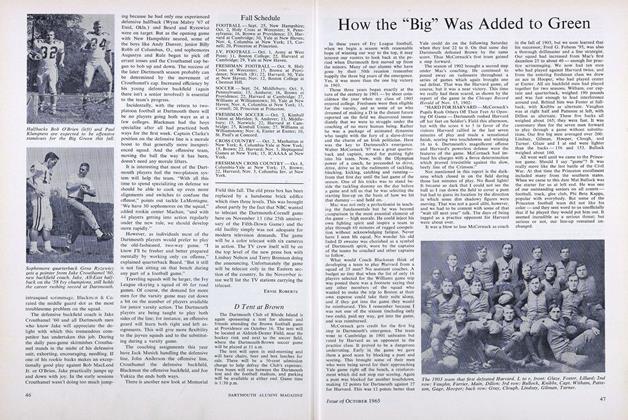

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

October 1965 By ERNIE ROBERTS -

Article

ArticleHow the "Big" Was Added to Green

October 1965 By W. HUSTON LILLARD '05 -

Article

ArticleA Rejoinder to Professor Segal's Article

October 1965 By RODERICK NASH

JOHN HURD '21

-

Books

BooksUNDER THE ROCK, POEMS FROM A VALLEY.

JANUARY 1968 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksBARBARY GENERAL, THE LIFE OF WILLIAM H. EATON.

APRIL 1968 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksSPAIN'S IRON AND STEEL INDUSTRY.

OCTOBER 1968 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Article

ArticleFurther Mention

OCTOBER 1971 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksALL THE BEST IN THE CARIBBEAN INCLUDING PUERTO RICO AND THE VIRGIN ISLANDS.

JULY 1972 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksEIGHTEENTH CENTURY STUDIES PRESENTED TO ARTHUR M. WILSON.

NOVEMBER 1972 By JOHN HURD '21