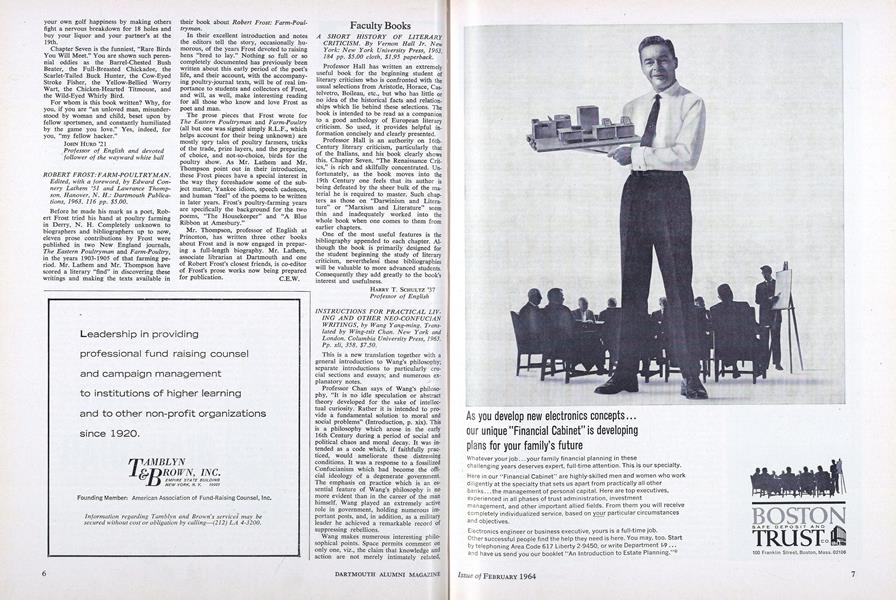

INSTRUCTIONS FOR PRACTICAL LIVING AND OTHER NEO-CONFUCIAN WRITINGS

FEBRUARY 1964 TIMOTHY J. DUGGANby Wang Yang-ming. Translatedby Wing-tsit Chan. New York andLondon. Columbia University Press, 1963.Pp. xli, 358. $7.50.

This is a new translation together with a general introduction to Wang's philosophy; separate introductions to particularly crucial sections and essays; and numerous explanatory notes.

Professor Chan says of Wang's philosophy, "It is no idle speculation or abstract theory developed for the sake of intellectual curiosity. Rather it is intended to provide a fundamental solution to moral and social problems" (Introduction, p. xix). This is a philosophy which arose in the early 16th Century during a period of social and political chaos and moral decay. It was intended as a code which, if faithfully practiced, would ameliorate these distressing conditions. It was a response to a fossilized Confucianism which had become the official ideology of a degenerate government. The emphasis on practice which is an essential feature of Wang's philosophy is no more evident than in the career of the man himself. Wang played an extremely active role in government, holding numerous important posts, and, in addition, as a military leader he achieved a remarkable record of suppressing rebellions.

Wang makes numerous interesting philosophical points. Space permits comment on only one, viz., the claim that knowledge and action are not merely intimately related, but are identical. This doctrine is put in the following way: "Knowledge in its genuine and earnest aspect is action, and action in its intelligent and discriminating aspect is knowledge. At bottom the task of knowledge and action cannot be separated. . . . Knowledge is what constitutes action and unless it is acted on it cannot be called knowledge" (p. 93).

Professor Chan says, "The type of knowledge [Wang] referred to is clearly limited to personal experience and does not exhaust the whole realm of knowledge" (p. xxxv). For example, I cannot know the taste of lemon unless I taste one; I cannot know love or pain or hatred unless I love, hate, or suffer pain. But perhaps Wang's doctrine can be related to another sphere of knowledge, viz., moral knowledge (indeed, one kind of example that Wang employs to support his claim is our knowledge of such "moral" principles as that of filial piety). One thinks here of the Socratic doctrine that to know the good is to do it. Of course, Socrates did not mean that if one knows that a certain kind of action is good or right that he continuously goes about performing that kind of action. Rather, such a person has a settled disposition, or tendency of the will to perform that sort of action in the appropriate circumstances. If we agree that such a disposition or tendency of the will is "the beginning of action," as Wang claimed, then his doctrine that knowledge is action appears to have direct application to the area of morality.

Assistant Professor of Philosophy

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

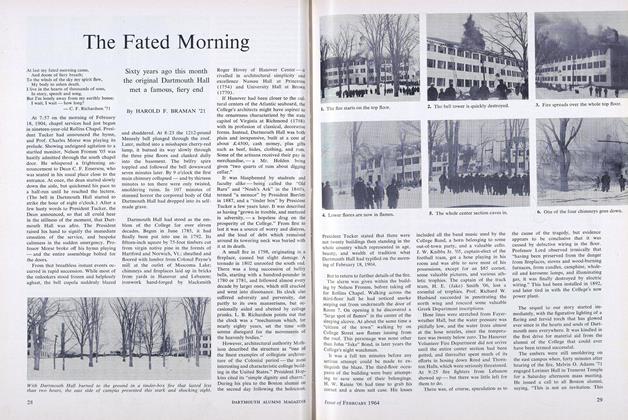

FeatureThe Fated Morning

February 1964 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21 -

Feature

FeatureBACK TO THE BOOKS

February 1964 By R.J.B. -

Feature

FeatureThe Cold, Cold World of CRREL

February 1964 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

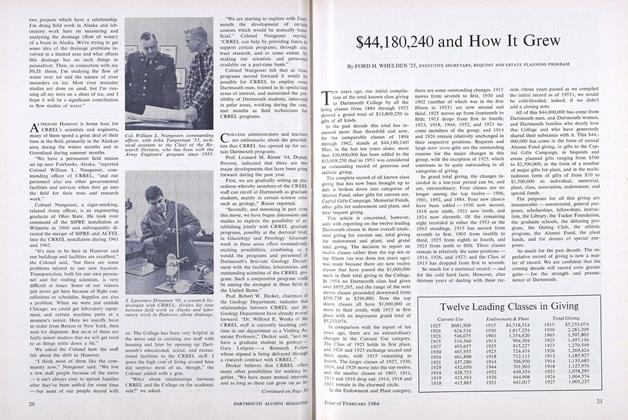

Feature$44,180,240 and How It Grew

February 1964 By FORD H. WHELDEN '25 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

February 1964 By DAVE BOLDT '63 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1936

February 1964 By BARRY C. SULLIVAN, E. JAMES STEPHENS JR.

TIMOTHY J. DUGGAN

Books

-

Books

BooksTHE PSYCHOLOGY OF RADIO

January 1936 By C. N. Allen '24 -

Books

BooksA Higher Law

December 1978 By CHARLES T. DUNCAN '46 -

Books

BooksPro-Am

October 1978 By MARSHALL LEDGER '61 -

Books

BooksVERMONT — IN ALL WEATHERS.

November 1973 By PENNINGTON HAILE'24 -

Books

BooksTHE STORY OF MOUNT WASHINGTON.

June 1960 By STEARNS MORSE -

Books

BooksPLANTER MANAGEMENT AND CAPITALISM IN ANTE-BELLUM GEORGIA.

July 1954 By W. RANDALL WATERMAN