By Albert William Levi '32.Bloomington: Indiana University Press,1959.591 pp. #7.50.

In his preface Professor Levi reports that lie has written primarily for "that intelligent and generally educated kind of audience which in France in the eighteenth century read with enthusiasm Newton's Principia and the Essays of David Hume; which in the early decades of this century flocked to hear Henri Bergson's lectures in the great lecture hall of the College de France; and which listened to Whitehead deliver the Lowell Lectures in Boston in 1925." Assuming that such an audience exists today, it will find in Philosophy and the Modern World an exceedingly readable and highly rewarding offering. Professor Levi has a genuine talent for explicating complex and often obscure doctrines. His language is never unduly technical, and yet he manages to present the material in a judicious and undistorted fashion.

"Philosophy and the Modern World has," Professor Levi tells us, "an ambitious subject matter. Its scope may be too large, but it represents my conviction that somewhere in this age of philosophical specialization and limited topics, there must be a place for a comprehensive treatment of the ideological foundations of contemporary civilization." The scope and comprehensiveness of treatment are exhibited by the table of contents. There is a chapter devoted to Bergson, one to Spengler and Toynbee, one to Freud and his followers. In addition there are chapters on Lenin and Veblen, Einstein and Plank, Dewey, Russell and Carnap, Jaspers and Sartre, Moore and Wittgenstein, and White-head.

One ought not to be intimidated by such a catalog of names. The chapter dealing with the revolutionary theses of Einstein and Plank may very well be the most difficult one of the lot, yet even here the presentation though uncompromising displays the lucidity which characterizes the book as a whole. The account of G. E. Moore's sometimes unbearably painstaking theorizing about sense-data and their relation to physical objects is just another instance of clear presentation of a highly complex issue.

I should not want to omit mentioning the two introductory chapters; chapters which I found particularly worthwhile. The first deals with the transition from the state of integration and synthesis characteristic of ancient Greece and mediaeval Europe to the fragmentation and dehumanization of contemporary civilization. The second deals with the conflict between eighteenth-century rationalism and nineteenth-century irrationalism and the problems that such a conflict poses for the man of the twentieth century.

Two of the dominant figures in twentieth-century Anglo-American philosophy are G. E. Moore and Ludwig Wittgenstein. Of them Professor Levi says, "Although I respect Moore and Wittgenstein, I think that theirs is finally a blind alley," and in another place he says, "The fruits of Moore's method and of Wittgenstein's linguistic emphasis are found in the 'Oxford Philosophy' of the last two decades." It is the author's opinion, moreover, that the fruits are for the most part shriveled and unpalatable, and that they represent a "preoccupation with the elaboration of the minute." With the exception of Gilbert Ryle the charge of "thinness and triviality of substance" is leveled against Oxford Philosophy.

I would like to conclude this review by suggesting that had Professor Levi concerned himself with various works in moral philosophy which are regarded as representative of Oxford Philosophy, the scene might have appeared less barren. I have in mind particularly The Place of Reason in Ethics, S. Toulmin, The Language of Morals, R. M. Hare, and Ethics, P. H. Nowell-Smith. None of these authors is included in the index. This, however, is but a minor criticism of a first-rate piece of work.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

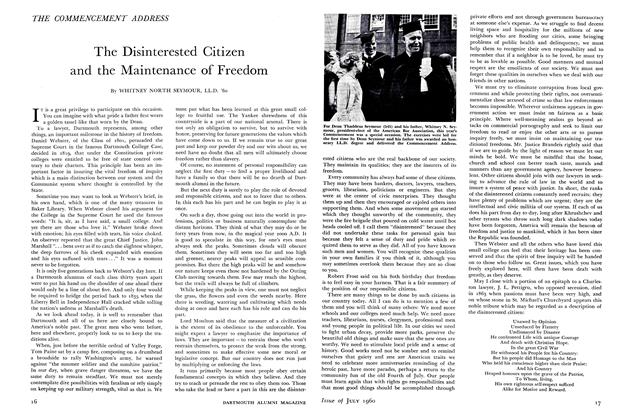

FeatureThe Disinterested Citizen and the Maintenance of Freedom

July 1960 By WHITNEY NORTH SEYMOUR, LL.D. '60 -

Feature

FeatureThe Fifty-Year Address

July 1960 By ANDREW J. SCARLETT '10 -

Feature

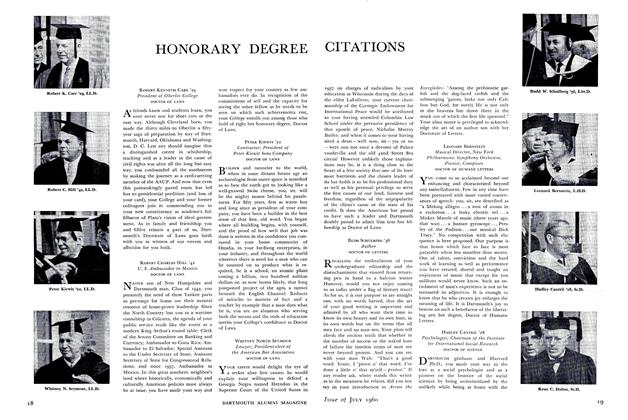

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1960 -

Feature

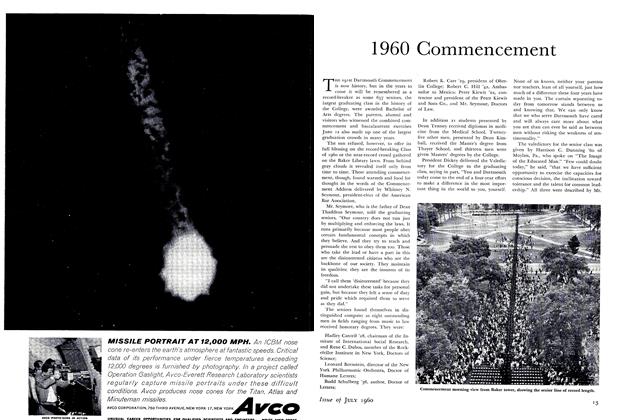

Feature1960 Commencement

July 1960 By D.E.O. -

Feature

FeatureThe Image of the Educated Man

July 1960 By HARRISON CASE DUNNING '60 -

Feature

FeatureThe Reunion Week

July 1960

TIMOTHY J. DUGGAN

Books

-

Books

BooksProfessor Gordon Ferrie Hull Jr. '37

February 1946 -

Books

BooksTHE DIGGING-EST DOG.

JANUARY 1968 -

Books

BooksThe Peacemakers of 1864

JANUARY, 1928 By H. Donald Jordan -

Books

BooksWAR BELOW ZERO

December 1944 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Books

BooksMY QUEST FOR FREEDOM

June 1945 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Books

BooksINDUSTRIAL RESEARCH AND TECHNOLOGICAL INNOVATION: AN ECONOMETRIC ANALYSIS.

DECEMBER 1968 By M. O. CLEMENT