By Moe Frankel '34. New York: The Center for AppliedResearch in Education, Inc., 1965. 118pp. $3.95.

In 1956, M. L. Frankel wrote a Foreword to a pamphlet by Prof. B. W. Lewis, Chairman of the Department of Economics at Oberlin College and Trustee of the Joint Council on Economic Education. Professor Lewis put down harsh and discouraging words about the attitudes of his fellow economists:

It would be fair, I believe, to characterize the attitude of most members of our profession toward economics in the schools as apathetic or hostile. There are some who are interested and a few who are actively interested and favorable; but most of us give no thought to the matter and, of those who do, most look with ill-pleasure upon the presence (and certainly upon any extension) of economics in secondary-school curricula. Those who speak out in the latter vein draw support from each other's bland assertions that "Economics cannot be taught to high school youngsters," and "If pupils in the schools are exposed to economics, they will simply have more to unlearn when they enter college."

Economists were not the only reluctant or hostile group facing Frankel in his role as Executive Director of the Joint Council on Economic Education. Educators, business and community interests, boards of education, and state legislatures all contributed their shares of doubt, opposition and misunderstanding. Thus, Frankel must feel a deep satisfaction when in 1965 the writer of the Foreword to his book can state:

Today economic education is a prime concern among thinking people throughout our country. That this is so seems to those who have labored long in the field to be a hope come true. Economic illiteracy has been a continuing concern to educators, business, labor, and agricultural leaders, and government officials for many years. No longer, however, do such leaders have to dissipate their energies in pleading the cause. The "cause" is now every man's "cause."

This book is powerful testimony to the continuing drive and interest of its author. Far from resting on his laurels now that he and a handful of others have won their battle for recognition of the need for economic education in the schools, Frankel has moved vigorously to the next step. He has written a lively and informative account of what has been done in a few schools and can be done in others to put into effect operating programs of economic education all the way from the first grade through the twelfth.

The book exhorts as well as informs. Economics, Frankel is confident, can be made understandable at all levels of education: personal and community economic concerns can be meaningfully related to overall national and international economic problems: the value judgments and political preferences underlying alternative economic policies can be identified and taught objectively: economic understanding is an essential attribute of informed and effective citizenry: economic methodology, especially if not taught as abstract theory, can make a valuable contribution to a student's way of thinking about and solving non-economic problems.

I must confess that at a few points I found myself unable to share Frankel's optimism. I could only gasp at his statement, "There is little in economics which cannot be grasped by children at any age as long as the concepts are related to the maturity of the youngsters." There are some economic concepts which cannot possibly be reduced to the necessary maturity level without severe distortion. But I put the book down with a feeling that no interested reader could escape being infected by the author's enthusiasm. The more this infection spreads, the better. I can only hope that Frankel's fine book is widely circulated among and carefully read by those currently concerned with secondary education.

Associate Professor of Economics

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureGraduate Study—Past and Present

November 1965 By PROF. LEONARD M. RIESER '44, -

Feature

FeatureThe Conscience of Liberal Learning

November 1965 -

Feature

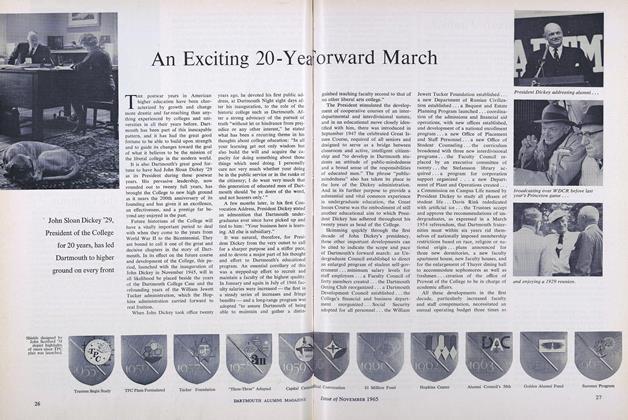

FeatureAn Exciting 20-Year Forward March

November 1965 -

Feature

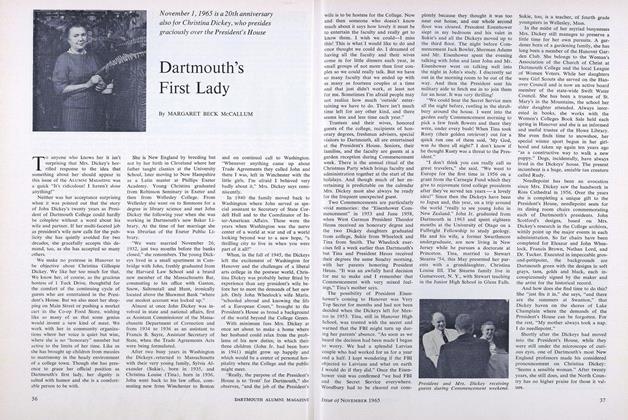

FeatureDartmouth's First Lady

November 1965 By MARGARET BECK McCALLUM -

Feature

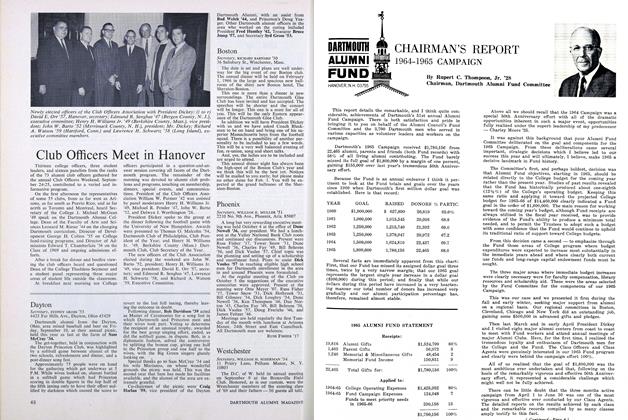

FeatureCHAIRMAN'S REPORT 1964-1965 CAMPAIGN

November 1965 By Rupert C. Thompson, Jr. '28 -

Feature

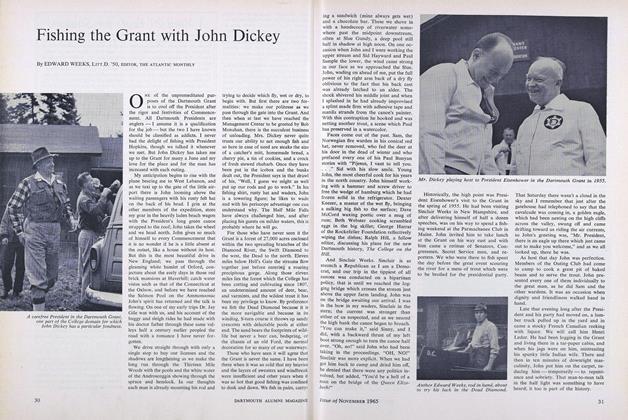

FeatureFishing the Grant with John Dickey

November 1965 By EDWARD WEEKS, LITT.D. '50,

Books

-

Books

BooksShelflife

Mar/Apr 2005 -

Books

BooksPROFESSORS' BOOK SHELF

Mar/Apr 2008 -

Books

BooksShelflife

Nov - Dec -

Books

BooksPHYSICAL CHEMISTRY FOR PREMEDICAL STUDENTS

October 1946 By ANDREW J. SCARLETT '10. -

Books

BooksTHE SEVEN LADY GODIVAS

January 1940 By Dr. Seuss -

Books

BooksOld World Traits Transplanted

August 1921 By Erville B. Woods