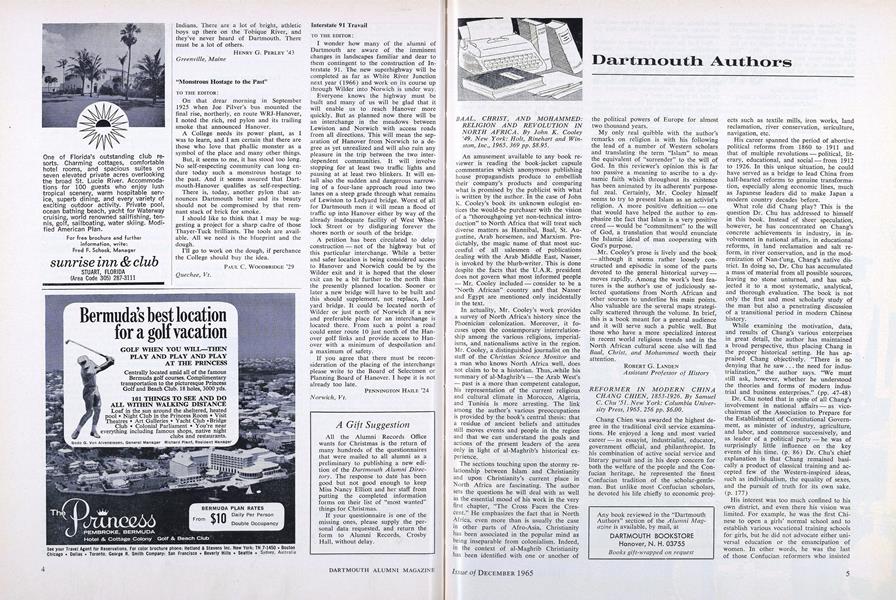

1853-1926. By SamuelC. Chu '51. New York: Columbia University Press, 1965. 256 pp. $6.00.

Chang Chien was awarded the highest degree in the traditional civil service examinations. He enjoyed a long and most varied career — as essayist, industrialist, educator, government official, and philanthropist. In his combination of active social service and literary pursuit and in his deep concern for both the welfare of the people and the Confucian heritage, he represented the finest Confucian tradition of the scholar-gentleman. But unlike most Confucian scholars, he devoted his life chiefly to economic projects such as textile mills, iron works, land reclamation, river conservation, sericulture, navigation, etc.

His career spanned the period of abortive political reforms from 1860 to 1911 and that of multiple revolutions - political, literary, educational, and social - from 1912 to 1926. In this unique situation, he could have served as a bridge to lead China from half-hearted reforms to genuine transformation, especially along economic lines, much as Japanese leaders did to make Japan a modern country decades before.

What role did Chang play? This is the question Dr. Chu has addressed to himself in this book. Instead of sheer speculation, however, he has concentrated on Chang's concrete achievements in industry, in involvement in national affairs, in educational reforms, in land reclamation and salt reform, in river conservation, and in the modernization of Nan-t'ung, Chang's native district. In doing so, Dr. Chu has accumulated a mass of material from all possible sources, leaving no stone unturned, and has subjected it to a most systematic, analytical, and thorough evaluation. The book is not only the first and most scholarly study of the man but also a penetrating discussion of a transitional period in modern Chinese history.

While examining the motivation, data, and results of Chang's various enterprises in great detail, the author has maintained a broad perspective, thus placing Chang in the proper historical setting. He has appraised Chang objectively. "There is no denying that he saw... the need for industrialization," the author says. "We must still ask, however, whether he understood the theories and forms of modern industrial and business enterprises." (pp. 47-48)

Dr. Chu noted that in spite of all Chang's involvement in national affairs — as vicechairman of the Association to Prepare for the Establishment of Constitutional Government, as minister of industry, agriculture, and labor, and commerce successively, and as leader of a political party — he was of surprisingly little influence on the key events of his time. (p. 86) Dr. Chu's chief explanation is that Chang remained basically a product of classical training and accepted few of the Western-inspired ideas, such as individualism, the equality of sexes, and the pursuit of truth for its own sake, (p. 177)

His interest was too much confined to his own district, and even there his vision was limited. For example, he was the first Chinese to open a girls' normal school and to establish various vocational training schools for girls, but he did not advocate either universal education or the emancipation of women. In other words, he was the last of those Confucian reformers who insisted on "Chinese learning for the foundation and Western learning for utilization." He did not catch the fire of revolution after all, although he was in the midst of it. Dr. Chu concludes, however (p. 182) "Had China had more men like Chang Chien .. . the country as a whole would have bene- fited enormously in her attempt to find a place among the developed nations of the world."

Professor of Chinese Cultureand Philosophy

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

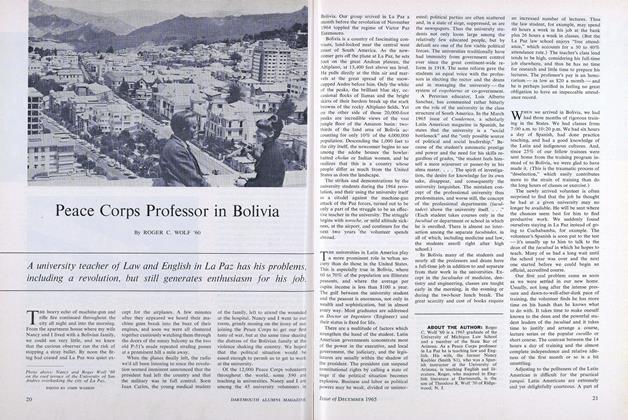

FeaturePeace Corps Professor in Bolivia

December 1965 By ROGER C. WOLF '60 -

Feature

FeatureBaker Holds the Key

December 1965 By JAMES W. FERNANDEZ -

Feature

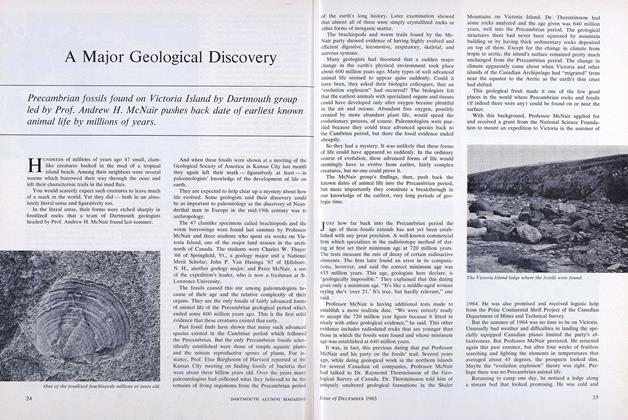

FeatureA Major Geological Discovery

December 1965 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

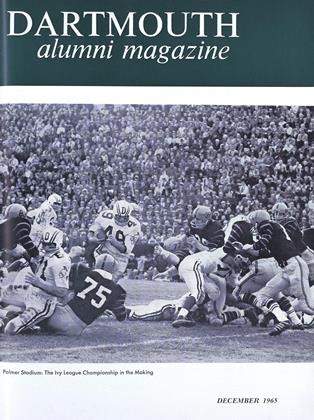

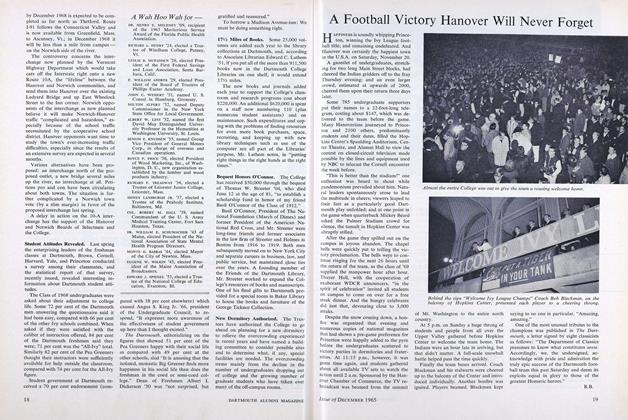

FeatureA Football Victory Hanover Will Never Forget

December 1965 By R.B. -

Article

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

December 1965 By ERNIE ROBERTS -

Article

ArticleThis Mother of Seven Dartmouth Sons Read Every Book in the College Library

December 1965 By JOHN HURD '21

WING-TSIT CHAN

Books

-

Books

BooksTHE DYNAMIC UNIVERSE

JANUARY 1932 By Charles A. Proctor -

Books

BooksBriefly Noted

FEBRUARY 1969 By J.H. -

Books

BooksTHE WEDDING BOOK.

NOVEMBER 1964 By PRISCILLA AND ALAN ROZYCKI '61 -

Books

BooksTHE QUARRY.

JUNE 1964 By ROBERTS W. FRENCH '56 -

Books

BooksTHE CHILD'S WORLD IN STORYSERMONS

November 1938 By Roy B. Chamberlin -

Books

BooksTHE ODES OF PINDAR,

April 1947 By Royal Case Nemiah