This Mother of Seven Dartmouth Sons Read Every Book in the College Library

DECEMBER 1965 JOHN HURD '21This Mother of Seven Dartmouth Sons Read Every Book in the College Library JOHN HURD '21 DECEMBER 1965

WITH more than 900,000 volumes and many foreign languages involved, the idea that any one person today could read all the books in the Dartmouth Library is preposterous. But there was a day when such an orgy of reading was possible, and a Ripley Believe It or Not cartoon pictures a Hanover mother in the early 1800's who not only raised seven Dartmouth sons but read every single book in the college library while doing it.

Ripley's Believe It or Not identified her as Mrs. Irene Foster of Hanover Center and described her as the mother of eight sons, all Dartmouth graduates, who during a period of 14 years took home to their mother every book in the college library. She read them all.

Believe it or not, there were only seven Dartmouth sons, not eight, but this is not to cast aspersions on the motherhood of Mrs. Foster, who presented her husband with ten sons and one daughter. Two sons died young. Of the seven graduated from Dartmouth, six became ministers.

Did she read every book in the Library? Library cards with her signed name do not exist; but neighbors' reports do; and they say yes. The Dartmouth Library in the days of Irene Burroughs Foster (born 1786, died 1854) was small enough to make it possible. In 1809 it had only 2,529 volumes of which some were children's books, bound magazines, and duplicates. A majority were religious. Furthermore, so old and battered were a number that in 1818 the Administration, hard up for cash, was willing to sell the Library for $2100 and buy books more useful to professors and students.

The desire of seven sons to make sure that their aspiring mother should be assured of library books may seem like a charming filial gesture, but more than a gesture was involved. At the time they were undergraduates, the Library operated under a quaint theory that books, zealously guarded under lock and key, should circulate as little as possible. Rules of 1802 were still pretty much honored: (1) For each class the Library was open for one hour only once a week. (2) Only five students might enter the Library at one time. (3) Only with the permission of the Librarian might a book be taken from a shelf. (4) Freshmen might borrow one volume at a time; sophomores and juniors, two; but seniors, presumably because of their greater intellectuality and maturity, were allowed three.

Some donors of funds to the Library stipulated that no books bought with their money should be taken out by a student. As late as 1859 President Lord stated that although the Library had been closed to students the entire spring term, except that books might be borrowed by special orders issued by professors, the students had suffered no inconvenience. The President consequently suggested that the Library be closed entirely for the forthcoming academic year to give the librarian a chance to catalogue new books.

In 1817, during the Dartmouth College Case, the "University" gained possession of the College buildings including the Library. Faculty and students of the College were consequently forced to use the libraries owned and run by the students, viz. the Society of Social Friends founded in 1783 and the United Fraternity founded in 1786, which had the intense loyalties and rivalries of the later Greek fraternities. These student libraries, each numbering some 2000 volumes, were the object of a battle between University and College forces, but by hiding their books in private quarters the student societies were able to retain possession.

The rivalry and power of students in nineteenth-century Dartmouth intellectual life may be suggested by the comparison of library collections. In 1860 after Greek letter fraternities had drained off much energy, the United Fraternity with 7,954 volumes had only two more than the Social Friends with 7,952; and the two student libraries combined actually owned more books than the College Library, 15,906 to 14,795. After complicated and extended negotiations, in 1874 the College took over the student libraries and unified the three collections.

As reader and mother of Dartmouth L sons, Irene Burroughs Foster was also a wife. Her husband, a farmer, Richard Foster, fought frosts and rocks and eked out from the stubborn soil enough to feed his children. But it was the mother who provided intellectual fare. She was determined that they should go ahead. Neighbors shook their heads and their dust pans at her passionate desire to keep up with her college-boy sons. Behind their hands they would whisper disparagingly, "She reads mornin's."

Who was Mrs. Irene Foster? A noncomformist, she was the daughter of a rebel, Rev. Dr. Eden Burroughs of Hanover Center, which, along the two-mile road, a half mile westerly from the center of Hanover, used to comprise about a dozen houses owing their existence to the location of the first meeting house. Mr. Burroughs, it was hoped, would prove a virile preacher, tough enough to stand up under New England rigors better than Preacher Knight Sexton, who wrote to President Wheelock a letter suggesting that he was something less than rugged:

Monday I was in great distress at my breast, and in almost a universal pain, and for some time spit clear fresh blood, and was left very weak. In the evening I had the Hickups extremely hard (my wife judged half an hour), till I was all in a sweat like a man mowing, and was very much afraid of losing my life by them. For some days I have been so troubled with boils that it has been difficult for me to wear my clothes; and in addition to this I have the itch very bad, and have reason to think my cold has struck it in, so as to be exceedingly hurtful to me, and I am told many times it proves to be dangerous. Last night came on my heel a stone bruise which is very painful, and is so bad that I am not able to go one step. My wife is not very well. I have not anybody to pity me or help me.

No stone would bruise Mr. Burroughs' heel. The pains he felt about his heart only strengthened him. When he sweated, it was with righteous anger. His itch was entirely irascible, and he was told many times that it (and he) were dangerous.

A tough-minded man, Mr. Burroughs made powerful friends and even more powerful enemies. He was never at a loss for words. Produced by a lover of controversy, his letters and sermons were black clouds filled with forked lightning on the Hanover sky. Inside church and outside, thunder rumbled about Mr. Burroughs.

The controversial question seems as tepid to us as it seemed hot in 1783. Innocuous today for us equipped with spiritual lightning rods, it seemed dangerous enough then to burn'down churches. It was: Could Dr. Burroughs be censured by the ruling elders of the Presbytery? "No," he cried vehemently. With dignified firmness the Grafton Presbytery said, "Yes."

Because Dr. Burroughs repeatedly refused to appear before the Presbytery to answer to charges, the Presbytery believed it necessary, even "indispensable ... to publish to the Christian Church and to the world that in our view Mr. Eden Burroughs has forfeited his title to our fellowship and communion as a minister and as a Christian."

Angrily, Dr. Burroughs and 56 members defied the decision, walked out of the meeting house, and with increased and persecuted fervor held religious services in private homes and in barns .until in 1791 they built the North Meeting House in competition with the repudiated South Meeting House. The defiant iconoclast, Mr. Burroughs, continued nonetheless to send in bills to the town for his services. Yearly appointed, committees. wrestled for some ten years with this slippery problem in which no firm holds could be established before 1801.

The lurid storm-lights playing about Dr. Burroughs became even more sinister in the shocked eyes of his adversaries when the son-in-law of President Eleazar Wheelock, Professor Sylvanus Ripley, a graduate of the first class at Dartmouth (1771), Missionary to. the Indians, Preceptor at Moor's School, Trustee of Dartmouth College, and Minister at the rival church, the South Meeting House, riding backwards in a sleigh in a blizzard after preaching was thrown out and died of a broken neck.

If Irene Burroughs Foster in her intellectuality defied censorious neighbors and if Mr. Eden Burroughs was cantankerous in his religious fervor, Stephen Burroughs, Irene's brother and Eden's son, was almost from the cradle a juvenile delinquent; at 14, a runaway enlistee in the Revolutionary Army; a hellraiser at Dartmouth until he was kicked out, at 16; a fraudulent ship's doctor on a lugger trip to France; a fake preacher with a diabolic smile reading to parishioners in Pelham, Mass., sermons he had stolen from his father; a counterfeiter, who got caught; a jailbird capable of flying through prison bars; manager of his father's farm; a Canadian refugee; a sincere convert to Roman Catholicism; a responsible school teacher in Three Rivers, Quebec; and father of a daughter who became an Ursuline nun, a son who became a pillar of the legal profession in Quebec City, and another son who became a well-to-do businessman in Montreal.

This rollicking rascal with such a flair for the bizarre so fascinated Robert Frost that he persuaded the Dial Press in 1924 to print his autobiography, "Memoirs of the Notorious Stephen Burroughs of New Hampshire." In his preface Frost suggested that the book be put on the same shelf with Benjamin Franklin and Jona than Edwards (grandfather of Aaron Burr). And Lincoln MacVeigh in a foreword describes it as of first-rate importance in its portrayal of eighteenth-century American cultural conditions as well as a first-rate story of adventure as lived by "a type of the Eternal Scamp."

The seven sons of Irene Foster were models of propriety if compared with her brother Stephen, but four were not lacking in unorthodox self-assertion.

The most conventional were Eden, William and Davis, all Congregational ministers.

The other four were more colorful.

Though no Stephen, Roswell did manage to get himself suspended from Dartmouth, as a letter from him to President Lord in the Dartmouth College Library Archives indicates. In beautiful handwriting and in earnest terms he requests permission for a return to college, promises improvement, hopes to "exert a Christian influence," assures the President that he is ready at once to take examinations in all subjects except Greek, and petitions for a four to six weeks delay to enable him to become more proficient in Horace. Readmitted, Horace and everything else in order, he was graduated to become a Congregational minister.

Richard, a teacher and farmer and a private in the lowa Infantry who rose to become adjutant of the Sixty-Second U. S. Colored Regiment of Volunteers, liked so well to work with Negroes that after the war he became Principal of Lincoln Institute, a colored school in Jefferson City, Miss.

Two sons were killed in the Civil War.

Charles, a lawyer practicing in Washington, lowa, a member of the lowa State Senate, wrote a book on the resources of California, enlisted as a private in the U. S. Volunteers, rose to become a major, and died, aged 44, of wounds received in Atlanta.

If Mrs. Foster's father was known as a fighting pastor, her son Daniel was a tough chip of the old block. No mere praying chaplain of the 33rd Massachusetts, Daniel at the battle of Chancellors ville, a self-appointed fighter filled with fury and fire, seized a gun from a nearby soldier and flung himself into the fray. So they dubbed him Fighting Chaplain, transferred him to the 37th U. S. Colored Volunteers, and promoted him to captain. Leading his black troops into battle at Chapin's Bluff, Captain Daniel was killed in action Sept. 30, 1864. He was 48 years old, too young to die. The average age of his Dartmouth brothers not killed in the Civil War was 74.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

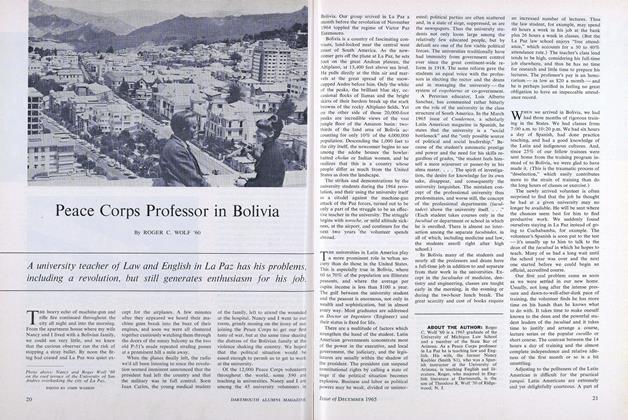

FeaturePeace Corps Professor in Bolivia

December 1965 By ROGER C. WOLF '60 -

Feature

FeatureBaker Holds the Key

December 1965 By JAMES W. FERNANDEZ -

Feature

FeatureA Major Geological Discovery

December 1965 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

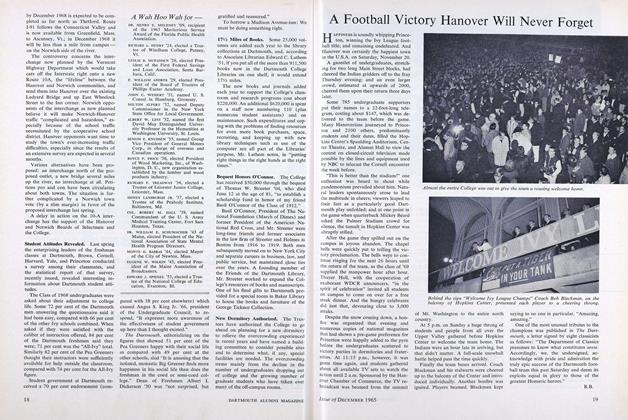

FeatureA Football Victory Hanover Will Never Forget

December 1965 By R.B. -

Article

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

December 1965 By ERNIE ROBERTS -

Article

ArticleThe Campus Examines Public Issues

December 1965 By LARRY K. SMITH

JOHN HURD '21

-

Article

ArticleTHE NEW FRONTIER

February 1953 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksWOODSMOKE AND WATER CRESS.

JANUARY 1966 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Article

ArticleDean of Travel Writers

OCTOBER 1968 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksTHE YOUNG MILLIONAIRES.

October 1973 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksVERMONT ALBUM: A COLLECTION OF EARLY VERMONT PHOTOGRAPHS

December 1974 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksBull Market

September 1975 By JOHN HURD '21