Precambrian fossils found on Victoria Island by Dartmouth groupled by Prof. Andrew H. McNair pushes back date of earliest knownanimal life by millions of years.

HUNDREDS of millions of years ago 47 small, clamlike creatures basked in the mud of a tropical island beach. Among their neighbors were several worms which burrowed their way through the ooze and left their characterisic trails in the mud flats.

You would scarcely expect such creatures to leave much of a mark in the world. Yet they did - both in an absolutely literal sense and figuratively too.

In the literal sense, their forms were etched sharply in fossilized rocks that a team of Dartmouth geologists headed by Prof. Andrew H. McNair found last summer.

And when these fossils were shown at a meeting of the Geological Society of America in Kansas City last month they again left their mark - figuratively at least — in paleontologists' knowledge of the development of life on earth.

They are expected to help clear up a mystery about how life evolved. Some geologists said their discovery could be as important to paleontology as the discovery of Neanderthal man in Europe in the mid-19th century was to anthropology.

The 47 clamlike specimens called brachiopods and the worm burrowings were found last summer by Professor McNair and three students who spent six weeks on Victoria Island, one of the major land masses in the arctic north of Canada. The students were Charles W. Thayer '66 of Springfield, Vt., a geology major and a National Merit Scholar; John P. Van Hasinga '67 of Hillsboro. N. H., another geology major; and Peter McNair, a son of the expedition's leader, who is now a freshman at St. Lawrence University.

The fossils caused this stir among paleontologists because of their age and the relative complexity of their organs. They are the only fossils of fairly advanced forms of animal life of the Precambrian geological period which ended some 600 million years ago. This is the first solid evidence that these creatures existed that early.

Past fossil finds have shown that many such advanced species existed in the Cambrian period which followed the Precambrian. But the only Precambrian fossils scientifically established were those of simple aquatic plants and the minute reproductive spores of plants. For instance, Prof. Elso Barghoorn of Harvard reported at the Kansas City meeting on finding fossils of bacteria that were about three billion years old. Over the years many paleontologists had collected what they believed to be the remains of living organisms from the Precambrian period of the earth's long history. Later examination showed that almost all of these were simply crystallized rocks or other forms of inorganic matter.

The brachiopods and worm trails found by the McNair party showed evidence of having highly evolved and efficient digestive, locomotive, respiratory, skeletal, and nervous systems.

Many geologists had theorized that a sudden major change in the earth's physical environment took place about 600 million years ago. Many types of well advanced animal life seemed to appear quite suddenly. Could it have been, they asked their biologist colleagues, that an "evolution explosion" had occurred? The biologists felt that the earliest animals with specialized organs and tissues could have developed only after oxygen became plentiful in the air and oceans. Abundant free oxygen, possibly created by more abundant plant life, would speed the evolutionary process, of course. Paleontologists were puzzled because they could trace advanced species back to the Cambrian period, but there the fossil evidence ended abruptly.

So they had a mystery. It was unlikely that these forms of life could have appeared so suddenly. In the ordinary course of evolution, these advanced forms of life would seemingly have to evolve from earlier, fairly complex creatures, but no one could prove it.

The McNair group's findings, then, push back the known dates of animal life into the Precambrian period, but more importantly they constitute a breakthrough in our knowledge of the earliest, very long periods of geologic time.

JUST how far back into the Precambrian period the age of these fossils extends has not yet been established with any great precision. A well-known commercial firm which specializes in the radioisotope method of dating at first set their minimum age at 720 million years. The tests measure the rate of decay of certain radioactive elements. The firm later found an error in its computations, however, and said the correct minimum age was 455 million years. This age, geologists here declare, is "geologically impossible." They explained that this dating gives only a minimum age. "It's like a middle-aged woman saying she's 'over 21.' It's true, but hardly relevant," one said.

Professor McNair is having additional tests made to establish a more realistic date. "We were entirely ready to accept the 720 million year figure because it fitted in nicely with other geological evidence," he said. This other evidence includes radiodated rocks that are younger than those in which the fossils were found and whose minimum age was established at 640 million years.

It was, in fact, this previous dating that put Professor McNair and his party on the fossils' trail. Several years ago, while doing geological work in the northern islands for several Canadian oil companies, Professor McNair had talked to Dr. Raymond Thorsteinsson of the Geological Survey of Canada. Dr. Thorsteinsson told him of uniquely unaltered geological formations in the Shaler Mountains on Victoria Island. Dr. Thorsteinsson had some rocks analyzed and the age given was 640 million years, well into the Precambrian period. The geological structures there had never been squeezed by mountain building or by having thick sedimentary rocks deposited on top of them. Except for the change in climate from tropic to arctic, the island's surface remained pretty much unchanged from the Precambrian period. The change in climate apparently came about when Victoria and other islands of the Canadian Archipelago had "migrated" from near the equator to the Arctic as the earth's thin crust had shifted.

This geological freak made it one of the few good places in the world where Precambrian rocks and fossils (if indeed there were any) could be found on or near the surface.

With this background, Professor McNair applied for and received a grant from the National Science Foundation to mount an expedition to Victoria in the summer of 1964. He was also promised and received logistic help from the Polar Continental Shelf Project of the Canadian Department of Mines and Technical Survey.

But the summer of 1964 was no time to be on Victoria. Unusually bad weather and difficulties in landing the specially equipped Canadian planes limited the party's effectiveness. But Professor McNair persisted. He returned again this past summer, but after four weeks of fruitless searching and fighting the elements in temperatures that averaged about 45 degrees, the prospects looked dim. Maybe the "evolution explosion" theory was right. Perhaps there was no Precambrian animal life.

Returning to camp one day, he noticed a ledge along a stream bed that looked promising. He was cold and tired and during the morning he had examined several similar ledges that had looked promising but yielded nothing. Still, it was worth the half-mile walk to investigate.

There he found the elusive fossils. "And when I did," he said, "I knew how gold prospectors felt when they stumbled across the mother lode."

He returned to camp with some specimens and immediately began plans to return the next day. However, the next four days were miserable and they couldn't move out of camp.

"I kept looking at the sky waiting for it to clear and then at the fossils, just to be sure I hadn't dreamed it all," he said.

Finally the party returned to the fossil site where they removed about 300 pounds of sedimentary rock containing fossils. The clamlike brachiopods were about a halfinch across and had two interlocking, paper-thin shells which were ridged with a clam's characteristic growth lines. The worm burrowings varied in size, but some were as much as a half-inch in diameter.

The Canadian Polar Shelf planes with oversized tires for the rugged terrain ferried the party back from Victoria to Mould Bay on Prince Patrick Island where the Canadians maintain an air base. From there they caught a commercial flight to Montreal and returned from there to Hanover.

Back at Dartmouth the slow task of classifying and cataloguing the specimens and preparing reports began. Colleagues and students had thousands of questions, about the fossils as well as the adventurous trip. The party members told about their find; about the near-record-size fish they had caught to give variety to the rations they carried; about the herds of musk oxen and caribou they had seen and photographed; about the sparse but strikingly beautiful arctic flora, and about naming several landmarks. They also were kept busy showing the color photographs of Victoria to the Geology Club's weekly luncheons.

And finally, the day before he left for the Kansas City meeting, for Professor McNair there was a simple ceremony at Pine Knolls Cemetery in Hanover. A 1400 pound stone from Ellet Ringnes Island in the Arctic was placed on the grave of Vilhjalmur Stefansson, the assembler and curator of the Stefansson Collection of Polar Literature at the College. Stef had been one of the first white men to explore Victoria Island and he had named the Shaler Mountains for a Harvard geology professor under whom he had studied.

The Stefansson Collection had given an early impetus to Professor McNair's interest in arctic geology. Some years before he had constructed a geological map of several of the islands without ever having set foot there. His primary sources were the accounts of explorers, missionaries, and others who had kept excellent journals that found their way into the collection. Canadian geologists who had begun studies of the area saw the charts and were amazed by their accuracy. This began an association that ended eventually in the major fossil find.

Steffansson's graveside seemed an appropriate place to be on the eve of the announcement of his findings.

One of the fossilized brachiopods millions of years old.

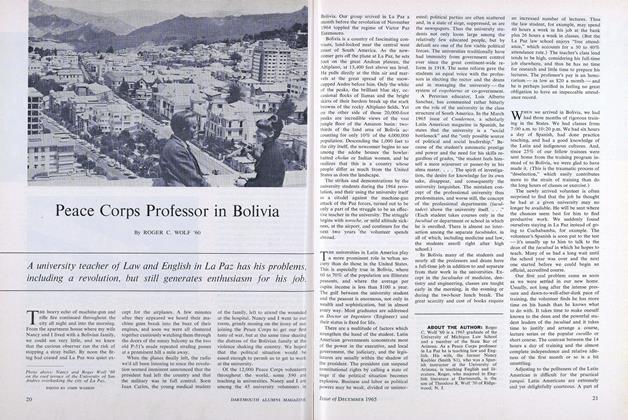

The Victoria Island ledge where the fossils were found.

Prof. Andrew H. McNair points to the spot north of the Canadianmainland where his party made its important discovery.Professor McNair, who took his A.B. and A.M. degrees at theUniversity of Montana and his Ph.D. at the University ofMichigan, has been a member of the Dartmouth faculty since1935. Much of his work has been in petroleum geology.

Fossilized worm trail embedded in sedimentary rock.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeaturePeace Corps Professor in Bolivia

December 1965 By ROGER C. WOLF '60 -

Feature

FeatureBaker Holds the Key

December 1965 By JAMES W. FERNANDEZ -

Feature

FeatureA Football Victory Hanover Will Never Forget

December 1965 By R.B. -

Article

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

December 1965 By ERNIE ROBERTS -

Article

ArticleThis Mother of Seven Dartmouth Sons Read Every Book in the College Library

December 1965 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Article

ArticleThe Campus Examines Public Issues

December 1965 By LARRY K. SMITH

GEORGE O'CONNELL

-

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

May 1962 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

MAY 1963 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

NOVEMBER 1963 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

MAY 1964 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Article

ArticleTuck School Author

FEBRUARY 1965 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty

APRIL 1966 By GEORGE O'CONNELL

Features

-

Feature

Feature"The Greatest Problem in American Biology

November 1983 -

Feature

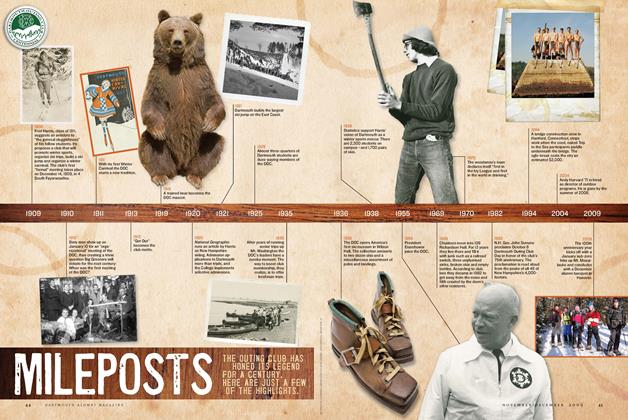

FeatureMileposts

Nov/Dec 2009 -

Feature

FeatureTo An Athlete, Aging

September 1992 By Mark Lange '84 -

Cover Story

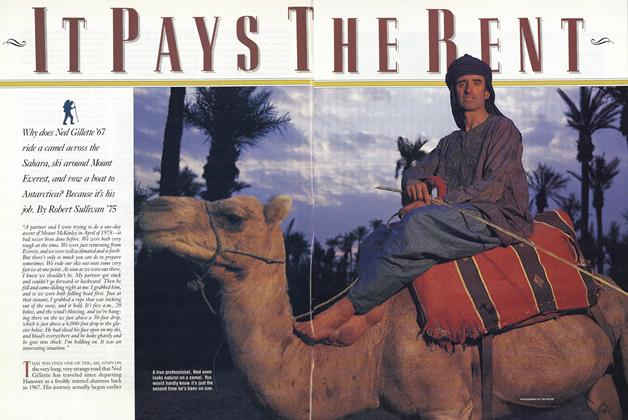

Cover StoryIt Pays The Rent

APRIL 1990 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Cover Story

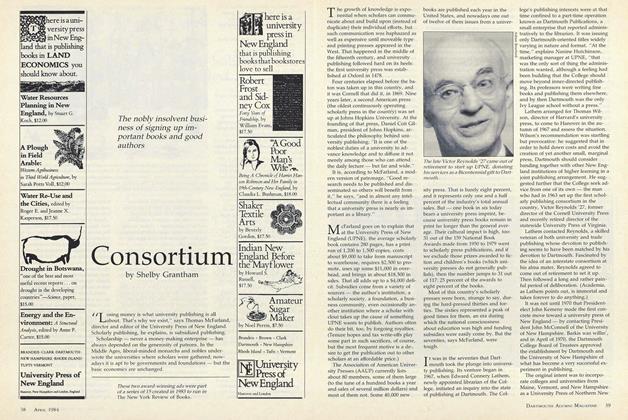

Cover StoryConsortium

APRIL 1984 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO NAB GREAT FREE STUFF FOR YOUR REUNION

Sept/Oct 2001 By TOBY REILEY '81