PROFESSOR OF CHINESE CULTURE AND PHILOSOPHY

ANY consideration of the future of Chinese civilization must be based on the fact that Communist China, which recently marked its tenth anniversary, is a going concern. If so, what is going to happen to three thousand years of Chinese civilization?

In the last ten years the Communists in China have not set out deliberately to destroy Chinese civilization, but their antitraditional attitude and activities are perfectly clear. In their eyes much of Chinese society and culture is feudalistic, and feudalism and imperialism, as understood by them, are their chief enemies. It is true that both Mao Tse-tung, the Party leader, and Liu Shao-ch'i, Chairman of the Government, used to quote Confucius, that the Confucian temple in his native place has been well preserved and redecorated, that traditional arts like landscape painting and the opera are encouraged and officially sponsored, and that Confucian classics are being published, to cite only a few examples. But none of these has affected Communist ideology or methodology in the least. They are being used as tools to serve the ends of the state, and can be thrown away at any time.

Traditionally, rebels and reformers have relied on ancient sages for sanction. The Communists have felt no need for any such authority. Traditionally, founders of new dynasties always claimed they had received the "mandate of Heaven" to rule. The Communists, however, have not made any such claim. Not only do they feel no need of traditional culture to sanction their regime; their culture is in many ways diametrically opposed to that of China. Theirs is a mass culture, unlike the culture of the elite in traditional China. In their new society the most important unit is the state rather than the family. They glorify youth instead of age. Their outlook is monolithic—one party, one idea, one method-whereas the Chinese people have preferred a multiple outlook, as in following three religions at the same time, being both a socialistic Confucianist and individualistic Taoist, or "pursuing two different courses without conflict." They resort to extreme measures while the Chinese usually choose moderation. Their government is a dictatorship whereas Chinese governments by and large have been laissez faire. In view of these facts, it is difficult not to conclude that Chinese civilization and Communism stand at opposite poles.

This being the case, many people fear that either the Chinese Communists will actively destroy Chinese civilization when they are ready or they will simply ignore it and let it gradually decline. The commune system seems to indicate the radical course, for it is not a temporary, emergent economic measure but a new way of life, removing the family as the foundation of society and reducing it to a rooming house. However, the fear that the communes herald the beginning of an active campaign against Chinese civilization is to a large extent unfounded. There are two outstanding facts to show that Communism and Chinese civilization are not irreconcilable and that there is no necessity for the Communists to destroy Chinese civilization, even if they could. One is that they have co-existed in the last decade. The other is that they have a number of points in common.

In spite of radical changes in Communist China, much of Chinese culture still continues. The news of "book burning" several years ago turned out to be a rumor. The folklore, the festivals, the literature, and other expressions of the national sentiment are very much alive. Neglected folk dances are being revived. Ancient poets are being sung for no other reason than their appeal to the Chinese mind. Ancient symbols are being used for designs and traditional crafts are being promoted. The various religions are going on. Of course they have to be subservient to the state, but they have done this before and survived. In the communes private property is virtually gone, but family life is not. Husbands and wives and their children are living together after all, although their freedom and activity are severely restricted.

Other evidences can be mentioned to show that Chinese civilization is still with us. This does not mean that it has not felt the impact of Communism. Imprints, perhaps permanent, have already been made on it. Labor, for example, which was traditionally looked down upon, is now elevated to the position of honor. Women have been emancipated from their housekeeping chores, thus creating a new concept and a new role for them. Literature and art have been revolutionalized; they are no longer meant for the purification of the emotions and the pacification of the heart, but for social reform. Heavy industrialization has been launched in such scale and pattern that the rural culture of old China will be radically transformed. A reasonably literate population is fast emerging with all its consequences on cultural configuration. These and other new developments will alter Chinese cultural patterns, in some cases beyond recognition. Nevertheless, Chinese culture has been modified more than once in history and has flourished. In fact, it has demonstrated a high degree of adaptability and stubbornness throughout the ages, and that is why it is among the few cultures that have persisted.

As to similarities, there are more than many people like to believe. Both Communism and Confucianism, which is the essence of Chinese civilization, conceive a Utopia in which all distinctions of classes, families, and nations disappear. Both envision an ideal state of perfect order and harmony which can be realized through social regulations and common loyalties and for which eventually very little government will be necessary. Both insist that government exists for the welfare of the people, with rulers acting the role of parents. In both systems the government is to be in the hands of the elite—the scholar-official in Confucianism and the cadre in Communism, both of whom, theoretically at least, are qualified to rule because of their ability, loyalty, and devotion to the social order. Both systems are characterized by an elaborate bureaucracy. In both systems the ideal man is the gentleman who studies and learns, disciplines himself strictly, watches over himself when alone, is absolutely sincere, follows a rigid code of conduct, and is thoroughly dedicated to public service. Both systems strongly stress that words and practice must correspond to each other. Reading Mao and Liu on the subject is like reading Confucius, Mencius, Wang Yang-ming the Neo-Confucianist, or Sun Yat-sen. Of course, Mao and Liu were speaking in terms of Marxian epistemology as understood by Stalin, but who can say for sure that the traditional Chinese equal emphasis on theory and practice was completely absent from their minds? At any rate, the similarity is striking.

Because of these similarities some scholars have concluded that Communism is rooted in Chinese civilization or that it is a natural product of it. Such a contention is unsound because it is based on half-truths. These scholars have overlooked that fact that in Confucianism social harmony is to be achieved through personal moral awakening instead of pressure from above. Likewise, Confucian paternalism is founded on the doctrine of humanity, that an innate feeling of love and commiseration should flow naturally from one's original goodness, which doctrine is utterly different from Communist reliance on force. The Confucian elite was a group of literary men whose qualities were essentially civil, contrary to the Communist cadres whose qualities are essentially military. Their study and self-discipline were voluntary, not under compulsion as in Communism.

Chinese tradition has always equally emphasized society and the individual, with the family serving as the training ground and the mediating point. In the family, members shared things together but at the same time each always had his or her place, obligations, and privileges. Common property, for instance, was balanced by each son's inalienable right to inheritance. State economy was considered as an "emergent" measure, whereas private ownership, individual business, and laissez-faire economy were the "standard. From these contrasts and many more, one wonders whether the similarities between Communism and Chinese civilization are not outweighed by their differences. For our present purpose, however, their similarities are significant because they show that not only can the two co-exist but they also overlap so that one may naturally exert influence on the other. If Communism has affected Chinese civilization, as already indicated, is it unreasonable to expect that Chinese civilization will affect Communism too? An age-old civilization is not likely to be eliminated by one stroke of the pen. No past ruler in China has tried in any big way and none has succeeded. The question is not whether Chinese civilization will survive but how and in what ways it can influence Communism.

IBELIEVE there are at least seven ways in which this influence is likely to take place. The first to be mentioned is the fact that the Communists themselves are Chinese. As such they cannot be entirely free from their cultural environment. No Chinese can be more Communistic than Mao, and yet the image of him as a man of shining moral influence, of poetic feelings, of fatherly conduct, and as a gentleman dedicated to social welfare has something distinctly Chinese about it. He is being portrayed as a Confucian superior man!

Secondly, in spite of the international character of Communism, the Chinese Communists are at the same time very nationalistic. The appeal to the people has been for patriotism to the country more than for loyalty to the Party. After all, Mao, Chou En-lai the Premier, and other Communist leaders are products of the patriotic movement of May 4, 1919, when Chinese students paraded and protested against the betrayal of China at the Versailles Conference. It is inevitable that because of their nationalistic feeling the Communists will find it imperative to accommodate Chinese culture.

Thirdly, while the Communists' control and regimentation of the population are among the most rapid and most extensive in human history, they, like any other rulers, have been anxious to get the support of the people. They claim that they came to power because of the support of the people, and now they must keep that support to remain in power. The people are not likely to give their support without the Communists' supporting them in return, and that means culture, not just rice. The primitive, animistic Taoist religion had been declining for decades. A coup de grace by the Communists would be most popular among Chinese reformers, although it is still followed by the ignorant masses. But two years ago, instead of suppressing it, they helped to organize a national Taoist association right in Peking, thus indicating the extent to which the Communists would go in seeking support from the people.

Fourthly, the Chinese Communists have been flexible. They are not too rigid or doctrinaire (as most Chinese are not). They did not hesitate to start with a peasants' revolution, although orthodox Communism called for a proletariat revolution. Their opposition to many aspects of traditional culture is therefore not absolutely unalterable. Besides, their definition of feudalism is so loose that it can be changed to meet the need. It was not many years ago when Kuo Mo-jo, leader of education and culture in Communist China, hailed Confucius as a rebel and a democrat.

Fifthly, Mao himself has declared that Communism should "absorb" the "democratic essence" of Chinese culture, for he contended that there are in it certain democratic elements. In the sixth place, there is a strong historical sense among the Chinese Communists, as among other Chinese. This does not mean that they look to the past or seek historical precedents as did the Confucianists. It does mean, however, that the Communist revolution is but a segment of Chinese history. Mao himself conceives of Chinese history as one of stages from primitive communism to feudalism to modern semi-colonialism and semi-feudalism. Communism, then, is understood by him as but a new stage. He assigns the beginning of the Communist revolution to the Opium War of 1840. Others have dated it the May 4 movement of 1919. Regardless of the date, the important thing is the recognition that the present cannot be cut off from the past, especially among a people who are peculiarly historically minded. Mao has insisted that we must "respect history," and that "we absolutely cannot be cut off from history." It is not a matter of accident that the study of historical sciences is among the best developed in Communist China and that the most remarkable achievement in research has been made in archaeology. Ancient sites have been discovered and historic places preserved. Because of this historical sense, everything is bound to be judged in an historical perspective. This means that the historical culture of China will not remain inactive.

Lastly, there is the intense humanism in Chinese tradition and society which the Communists cannot ignore. It has been the dominant factor in Chinese government, art, and even religion, for it has been the traditional conviction that good government depends on good men, that art exists for man's mental peace and spiritual harmony, and that religion is primarily meant for moral education. Consequently human relations and human values have been the chief concerns of Chinese people. In the Communist effort to bring about a socialist society, human values are being undermined by treating human beings primarily as economic units, by subordinating human relations to economic needs, and by treating the relationship between husband and wife and parents and children in the communes as secondary to that of the total group. Many Chinese are willing to suffer from conscript labor, if their standard of living can be raised. But when it comes to a sacrifice of simple human values and basic human relations, they will not tolerate it. Already the reaction to the communes has forced the Communists to allow children to stay with their parents.

ARE there any evidences that Chinese civilization is having an impact on Communism in China? Here we may be too optimistic, but from a broad point of view there are unmistakable signs that it is. Take, first of all, the Chinese intellectuals. Traditionally they have been the elite, the gentlemen, the nerve center of Chinese society. They have been the ones who directed the developments of Chinese government, art, and religion. In Communist China the intellectuals have been required to confess and to follow the party line, it is true. But the striking fact is that many non-Communist intellectuals are in the government, some in important positions; that as a group they still exist and even exert some influence, though not enough to veto Communist policies; and that not a single intellectual of national standing has been liquidated. There is reason to believe that Mao, Liu, and Chou, themselves intellectuals, have taken their fellow intellectuals more seriously than Communist leaders in other countries have taken theirs. It will be recalled that when the "Let one hundred flowers bloom" policy was adopted, it was the vigorous criticism of the intellectuals that shocked the Communists.

The "Let one hundred flowers bloom and let one hundred schools contend" policy itself is indicative that something basically Chinese is at work. The policy itself has been interpreted as a trick to fish out opposition. Actually the Communists knew very well where the opposition was. It has also been said that Mao needed to keep the tension going because the continued existence of Communism depended on it. Be that as it may, we may ask why he chose to use the traditional concepts of "one hundred flowers" and "one hundred schools" (which contended in the third and fourth centuries B.C.). One cannot help feeling that the typical Chinese multiple outlook was asserting itself. The Chinese like to say, "one hundred roads to the same destination," and "one hundred deliberations to the same conclusion." The "leaning to one side" (Russia) movement of several years ago was never popular and was soon abandoned.

Internally, in spite of absolute one-party rule, the stress has been on many parties participating, though only in theory. Externally, Southeastern Asia is not regarded as pro- or anti-Communist but as a neutral bloc or a third group. In short, the Chinese multiple outlook is discernible at many points. When Mao emphasized that "universal contradiction" and "particular contradiction" involved each other, or when Liu wrote that nationalism and internationalism involved each other, one cannot help recalling the One-in-All and All-in-One philosophy in both Buddhism and Confucianism. Is it not possible that a Chinese pattern of thought is silently and subtly making itself felt? In fact, the Common Program of the Communists strongly emphasizes the balance between country and town, between agriculture and industry, between nationalism and internationalism. Is this not a reflection of the traditional golden mean?

All this is not to suggest that Chinese civilization is transforming Communism. But it does mean that through such patterns as multiple outlook, moderation, and humanism it will soften Communism. Chinese civilization changed Buddhism from a rigid religion of individual salvation into a liberal religion of universal salvation. It changed the military Manchu regime into a civil and literary one, better known for libraries, arts, and crafts. And it changed Christianity from a denominational religion centering on the clergy to a non-denominational one centering on the layman. May it not do a similar thing with Communism?

Recommended Reading

Gluckstein, Ygael, Mao's China: Economic and Political Survey, Boston: Beacon Press, 1957. A popular yet solid treatment.

Tang, Peter, Communist China Today, Vol. 1, New York: Praeger, 1957. Scholarly, objective, analytical and clear. Vol. 2 contains statistics and a chronology.

Walker, Richard L., The Continuing Struggle: CommunistChina and the Free World, New York: Athene Press, 1959. A vigorous and critical appraisal.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureOur Place in the Sky

November 1959 By PROF. MILLETT G. MORGAN, -

Feature

FeatureSocial Responsibility in Painting

November 1959 By CHARLES T. MOREY, -

Feature

FeatureThe Commitment of Fellowship

November 1959 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY -

Feature

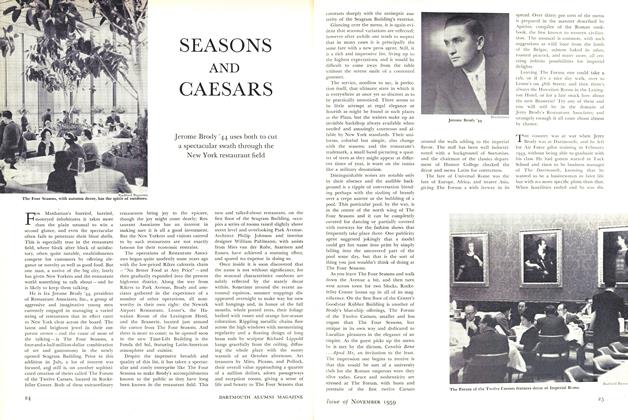

FeatureSEASONS AND CAESARS

November 1959 By JIM FISHER '54 -

Feature

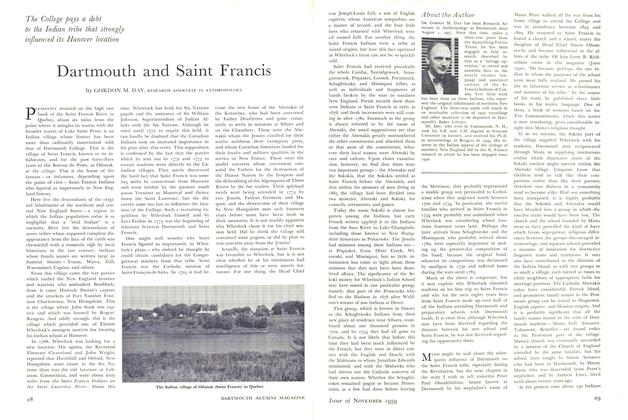

FeatureDartmouth and Saint Francis

November 1959 By GORDON M. DAY -

Article

ArticleHow I Conquered Alcohol

November 1959 By ALAN COOKE '55

WING-TSIT CHAN

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryDinesh D'Souza '83

March 1993 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryTHE CAT IN THE HAT

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

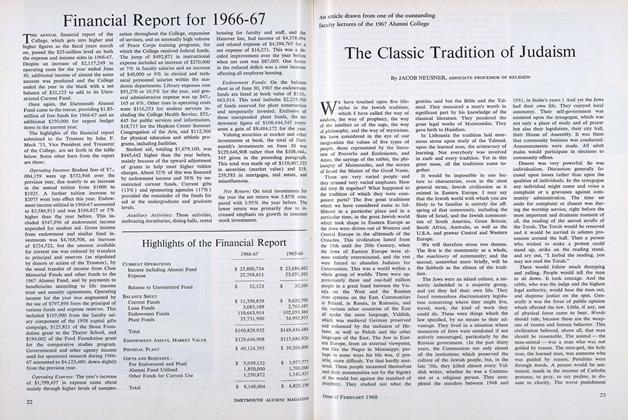

FeatureThe Classic Tradition of Judaism

FEBRUARY 1968 By JACOB NEUSNER -

Cover Story

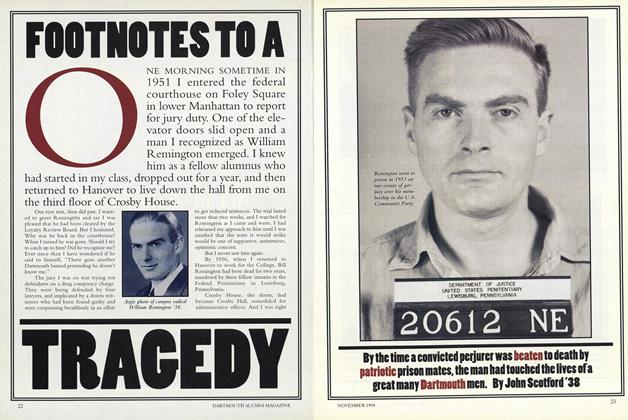

Cover StoryFOOTNOTES TO A TRAGEDY

November 1994 By John Scotford '38 -

Feature

FeatureThe View from Oxford

NOVEMBER 1971 By Sanford B. Ferguson '70 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryFather In Law

Nov/Dec 2000 By SARAH JACKSON-HAN ’88