UNDERGRADUATES, admissions officers, and counselors all over the East must have shaken their heads at the story on "The Freshman Blues" in Life Magazine's issue of January 8. Yale freshman Timothy Thompson, a high school honor society president from a small Oregon town, was portrayed taking his lumps in the classroom, and painfully making his adjustment to life in Yale's fast company.

In substance there couldn't have been much that was untrue about the article, but its approach reflected much of the old suspicion of the Ivy League. The only apparent alternatives for an "outsider" are brilliant success or shameful failure; no depth is given to the educational motive itself.

In picture and word, the reader followed a grim struggle; Tim seemed to be losing on all fronts: second man in his high school class of 176, he suddenly found himself with an average considerably below the middle of the Yale freshmen. The shadow of failure hung over his head; telling him that his was a common predicament didn't help.

A big picture outline trumpeted: "His clean-living Baptist ways make Tim a set-up for 'cultural shock,' " and the article went on to detail the social frustrations that are the common heritage of Dartmouth men as well. He is depicted as the only boy without a date at a Yale-Princeton party. "I can't just head for old friends here. I don't have any," he laments.

The concluding text rehearses the familiar complaint that the pressure for grades, for admission to preparatory schools, etc., is reaching further and further down into vulnerable childhood. It also presents some appalling, if distorted, figures on the number of psychi- atric cases at one prominent Eastern college.

All of this is pretty old-hat for those of us who have been reading contemporary comment on our collective progress from the time we first felt the needle back in the eighth grade. Nevertheless, it is rather chilling to observe that those al-mighty SAT scores of this year's Dartmouth freshmen are some 25 points higher than were those of the present seniors. If the rate of acceleration continues to increase, the time may be near when not only their fathers, but the undergraduates themselves will have to say that they could no longer get into Dartmouth on their secondary school records.

So the hazards and the heartbreak of the "education race" have become as common fare in the big-selling magazines as features on sexual mores, living modern, or the Kennedy family; the same old cliches are trotted out each time a class enrolls and graduates. What the Life article might have considered, but fell short of asking, was whether the rewards of the pursuit are worth the accumulated pain of those who don't make the proverbial grade.

The question would have brought back reflections of the past three and a half years at Dartmouth, in which you could see and feel the quickening all about you; and you had to watch for it and pick up a step or two at the right moment, to avoid being c.aught short.

THERE'S no question though that we're riding with a juggernaut, for better or for worse. Some fall off and get crushed, and all of us sometimes wonder how we got here. But if there is an answer to the despair in which the Tim Thompsons among us now find themselves, it has to be the ideal of the liberating education, which Life ignores in favor of more sensational revelations: another Yale freshman slams his fist down on a desk and complains that he gets only six hours of sleep on a good night. "I don't know what they're trying to do to us," he wails. "I'll do the work because I want the grades, but there's just no end to it."

Of course there never was, and there never will be an end to it. But with a little different attitude the same fellow would see instead of a crushing burden, an incomparable richness, and would realize how short is the time given him to utilize it.

It may be that only a view to such remote ideals can sustain some men through the day-to-day difficulties of the first two years in "the colleges of their choice." If not, hopefully it can send them elsewhere with faith in the worth of the process itself, which is far beyond the measure of Dartmouth's or anyone else's degree.

Here in Hanover especially, where the work load, the isolation, and the cold can combine into a seemingly impossible burden to the freshman - or even to the sophomore, whom the passing of a year might have shown that for the grimness of March there is also the glory of May - the temptation sometimes seemed irresistible to retreat to the relative ease of other schools and other settings. By the end of that second year a man usually knows he could have gone back to State and breezed through if he has proven himself here. But those who leave never know.

GRANTING the pressures for admission to graduate school and top jobs, as well as the social pressures within and without the College, there is another aspect of "Crackups on the Campus" whichre reflects new light on the figures which sensation-seekers would throw out to you. The entire complexion of college guidance has been profoundly influenced by advances in psychiatry and related sciences, and professionals in these fields have come to share in, if not to take over, a much larger portion of the counseling function.

Life claims that two out of ten American students need psychiatric help during their undergraduate years, and that about half of them get it. One may wonder who decides which student needs psychiatric help and which one simply gets the boot and an admonition to "grow up" before coming back. At Dartmouth, lack of motivation is considered a psychological problem; if there is one thing we have learned from studies of human personality as far back as Philosophy 25, it is that "growing up" in the ability to manage one's education is a never-ending process. The presumption is that no one in the College lacks the intellectual equipment with which to make a career here, so every effort ought to be made to keep him from failing.

Weekly conferences between the deans and psychiatric personnel at Dick's House seem to be only the beginning of this effort. New this year is a weekly seminar for freshman advisers under Dr. Raymond Sobel, assistant director of the College Health Service. Some 15 to 18 of these faculty members join each session. A similar program is also run for the entire Dick's House staff.

All of this is part of what might be called the greater "social visibility" of psychiatric care in today's culture, where we are recognizing and attacking the psychological bases of an entire range of problems which our grandparents either hid, refused to recognize, or accepted as normal.

Dr. Sobel points out too that a generation of studies has shown that, in general, more creative and imaginative personalities also have a high order of psychological problems and complexities. But there is little doubt that the College will continue to place increasing value on those very qualities, in admissions, and hopefully in educational policy.

BETWEEN the time-honored cliches which surround the liberal education, and the cautious cliches with which we talk about the science of personality, there may yet be a basic sociological problem about the role of the American college student.

So suggests Nevitt Sanford, director of the Institute for the Study of Human Problems at Stanford, and editor of an 1100-page volume on The American College, which is now available in brief under the title College and Character.

In an essay entitled The Freshman Personality, Sanford discusses the problem of identification in the period of late adolescence which intervenes between adolescence proper and early adulthood, and may cover any, or even all, of the undergraduate career. This stage is characterized by what he calls the authoritarian personality: inhibiting impulse, morally strict, both with self and with others, "ready to meet stiff requirements, to work hard, to conform, . . . and inclined to be somewhat intolerant of those who do not."

But the psychologist points out that "in the relative anonymity of the college society the student can be free of his home community's limiting expectations and can be himself in a variety of new social roles." What is called for then is the ability and the willingness of the student to let himself be "enveloped by the situation's demands" - the "process that expands and differentiates the personality." But a basic stability must underlie the person's self-conception before such freedom can exist.

The alternatives are what Sanford calls "short-cuts to maturity: imitating adult behavior and prematurely fitting into adult roles." Obviously this has a lot to do with the American tendency toward viewing children as miniature adults.

The essay concludes that "The college must in effect tell him, 'You are going to change. It is all right, therefore, for you to feel uncertain about your future; what matters is that you enter fully into those activities that can develop you.' In other words, what we need is a stronger definition and greater social acceptance of the role of student, so that those who occupy this role may more comfortably and easily be what they are - developing persons."

This would imply a solution to the problem of the bright student who is dissipating his energies in worrying; finally it is an alternative to the meanness of the modern collegiate success ethic. Moreover it has important implication for problems which are going to be very much with us in the next year, particularly the growing split between academics and extracurricular activities, which is currently under study by the faculty.

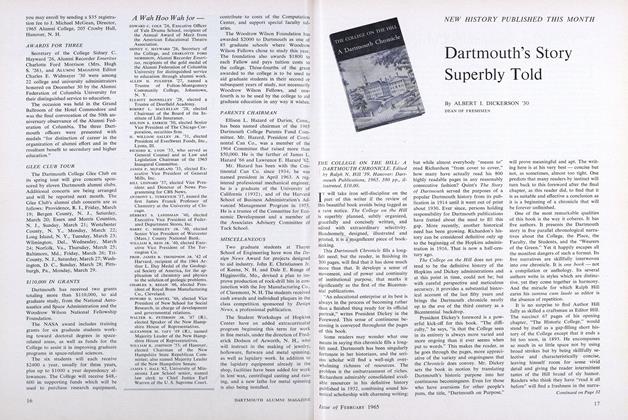

During Ledyard Canoe Club's Christmas-vacation treat for boys of the Hanoverarea, George Linkletter '65 steers a saucer slide, and (below) Mike Lewis '65 andLee Ward, sister of Peter Ward '65, provide fun at the clubhouse.

During Ledyard Canoe Club's Christmas-vacation treat for boys of the Hanoverarea, George Linkletter '65 steers a saucer slide, and (below) Mike Lewis '65 andLee Ward, sister of Peter Ward '65, provide fun at the clubhouse.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA NEW BREED OF CHUBBER

February 1965 By JOHN ALDEN THAYER JR. '65 -

Feature

Feature"It Was Quiet, Serene, and Beautiful"

February 1965 By GEORGE R. ANDREWS '37 -

Feature

FeatureBusiness Still Draws Its Share of Graduates

February 1965 By ADDISON L. WINSHIP '42 -

Feature

FeatureFreshman-Sophomore Curriculum Revised

February 1965 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth's Story Superbly Told

February 1965 By ALBERT I. DICKERSON '30 -

Article

ArticleThe Battle of the Non-Teachers

February 1965 By M. DANIEL SMITH '46

BOB WILDAU '65

-

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

NOVEMBER 1964 By BOB WILDAU '65 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

DECEMBER 1964 By BOB WILDAU '65 -

Article

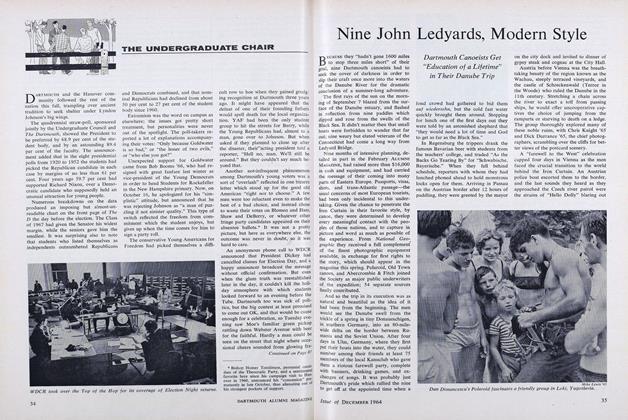

ArticleNine John Ledyards, Modern Style

DECEMBER 1964 By BOB WILDAU '65 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

JANUARY 1965 By BOB WILDAU '65 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

MAY 1965 By BOB WILDAU '65 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

JUNE 1965 By BOB WILDAU '65

Article

-

Article

ArticleC. F. CRATHERN '20 RETURNS FROM WORK IN NEAR EAST

November 1921 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Council Elections

February 1947 -

Article

ArticleAirport Boost

MARCH 1959 -

Article

ArticleCollege Calendar

NOVEMBER 1972 -

Article

ArticleClub Calendar

MAY • 1988 -

Article

ArticleChanges Lie Ahead for the Liberal Arts College

November 1942 By Irwin Edman