Two basic changes in the freshman-sophomore curriculum affecting the distribution requirement and the time of choosing a major course of study have been approved by the Dartmouth faculty. Three other proposals that also came out of the Committee on Educational Policy's year-long examination of the first two years of the Dartmouth experience were referred back to the committee for further study and revision before full faculty review.

The two changes in the curriculum, to be implemented by the Executive Committee of the Faculty, are:

(1) That the present distributive requirement be replaced by the follow- ing: Before graduation the student must pass (complete with satisfactory grade), or be awarded proficiency credit for, at least four courses among the offerings of each division, not including English 1, Language 1, 2, 3, or courses taught by the Departments of Air Science, Military Science, and Naval Science, with the following stipulation: That in the division in which the student's major subject is based he must include at least four courses outside his department of greatest concentration.

and:

(2) That all students be required to elect a major by the end of the third term of the sophomore year, and that they be permitted to do so at any time after the first term of the freshman year.

At present, the distributive requirement must be met in two years rather than four, and the major cannot be chosen before the third term of sophomore year.

In presenting its recommendations to the first of four meetings of the full faculty held in less than a month, the Committee on Educational Policy stated that it had undertaken the examination of the first two years of the Dartmouth curriculum "to determine if our present offerings and requirements took cognizance of the changes which have taken place in secondary school education and of the improved quality of entering classes.

"We wanted to know," the Committee's prepared report goes on, "whether the optimum conditions in intellectual climate and educational opportunity existed or not, and if they did not we hoped to discover means by which present practices could be changed so as to come closer to creating the optimum."

Three significant changes on the Dartmouth campus, as well as in the world of education at large, were evaluated, keeping in mind not only historical perspective, 50 years of curriculum growth, but also possible needs of the students of 1974 as well as those known in 1964. Of special importance to the consideration were the figures, studies, and faculty reports showing how markedly the intellectual quality of the entering students had improved. In the past decade average verbal and mathematical aptitude scores have risen approximately 120 points (verbal: 530 to 650; mathematical: 580 to 700). In addition, high school curricula have reached out to provide students with work in all areas once covered (and too often still covered) in the first two years. Many new Dartmouth students, the report continues, are not only brighter than ever and better prepared but they arrive on campus already knowing what subject they want to specialize in and are eager to get started.

The second change considered the relatively young faculty and "the health of Dartmouth's intellectual climate for the professionally oriented faculty member," the teacher-scholar so necessary to challenge the young men who succeed in Dartmouth's admissions competition.

The third change was found in "the ends toward which our students are striving." On this subject the Committee on Educational Policy wrote: "The over-whelming majority of Dartmouth students in recent years have gone on to advanced study of one kind or another in preparation for professional and scholarly careers. To meet the needs of these men departments have introduced more specialized work in their major, in some cases redesigning major programs along the lines of pre-professional preparation. Accompanying this increased specialization has been a growing need for a broad cultural background to equip students to live imaginatively and responsibly in our contemporary world."

The Committee next set out to see how these worthy objectives could be accomplished in nuts-and-bolts practicalities of what Dartmouth should offer in the classroom. There was an obvious need, the Committee concluded, "to make the first two years more distinctively a college experience as contrasted with what is for some students a mere extension of secondary school." How? Improve the intellectual climate; challenge the students; move them more rap- idly into areas of great interest to them; allow more latitude in the selection of courses; provide for varying needs, aptitudes, and interests of the individual student.

WHAT exactly has been changed and what are the possibilities in the two recommendations now approved by the Faculty?

In recent years the degree requirements to be completed in most cases before the end of the sophomore year called for three term-courses in Humanities to be chosen from a list of introductory offerings in Art, Music, Philosophy, Religion, etc., with "ors" abounding to limit the student's choices in any one department. For the Social Sciences requirement the student had to have four term-courses "of which at least one must be from each of the following groups and of which no two may be in the same department." The groups listed were (1) Government 5 or 6, Economics 1; (2) Psychology 1; Sociology 1 or Anthropology 1; and (3) History 1 or 2 or 5 or 6, Geography 1. There also were three groupings of courses in the Sciences with twice as many "ors" in evidence along with asterisks specifying laboratory courses, for one of the four courses had to have laboratory or small group discussions. The student was limited to no more than two from any one science department, but he had to have courses from two of the three groups and two courses that were sequential (i.e. Chemistry 3-4).

These requirements were meant to expose the student to a wide variety of disciplines, but as the Committee pointed out, "the effects of these regulations have been to make courses offered for distribution relatively elementary and sometimes repetitive of high school work, to crowd them into the first two years, and to force all students to sample a greater variety of courses than may be profitable in individual cases."

While the Committee questioned the value of forced feeding of sample dishes "served up by different departments," it did recognize "the value of an exposure to the methodology, the questions, and hopefully some of the answers involved in the different disciplines." The distributive requirement was retained, but on a completely different basis.

The student now must take beforegraduation, i.e. within a four-year rather than a two-year period, at least four term-courses in each of the three divisions - not including English 1, Language 1, 2, 3, and ROTC courses - and in the division from which he chooses his major he must include at least four courses outside the department in which he is majoring. Courses taken in the major cannot be used to meet the distributive requirement. He can take four courses in Economics to satisfy his Social Science if he chooses or he can spread them out as before among introductory courses or he can delay his concentration in one division whatever course of studies he decides upon will be of his making, determined by his interests, designed to meet his individual educational goals and at the same time he will have "the benefit of meaningful exposure to work in different disciplines." In many cases this work will be done in advanced sections: "the student, would not be forced to limit' himself to work that is largely elementary or introductory."

THE need for the second recommendation, allowing a student to select his major field of study sooner, grows out of the change in the distributive and course requirements. The capable and committed student who has determined his intellectual goals can move steadily and swiftly at a pace he himself sets toward meeting those goals. With an early selection of a major he will have the benefit of counseling in his chosen department. In many cases the College's problem in dealing with the counseling void between the freshman adviser and the junior-year counseling by the major adviser will be met naturally and personally.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

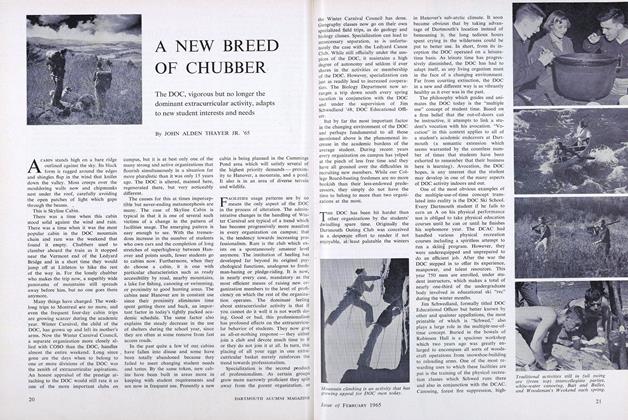

FeatureA NEW BREED OF CHUBBER

February 1965 By JOHN ALDEN THAYER JR. '65 -

Feature

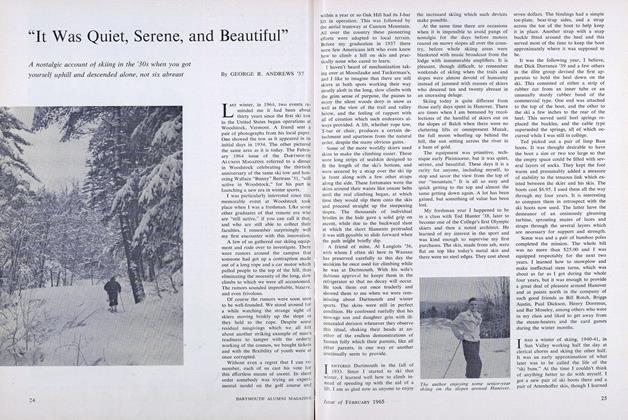

Feature"It Was Quiet, Serene, and Beautiful"

February 1965 By GEORGE R. ANDREWS '37 -

Feature

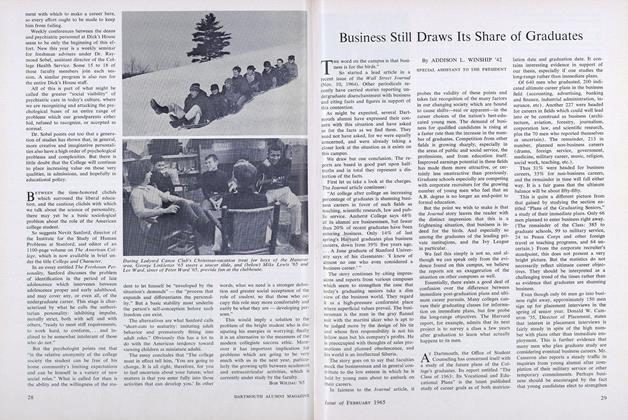

FeatureBusiness Still Draws Its Share of Graduates

February 1965 By ADDISON L. WINSHIP '42 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

February 1965 By BOB WILDAU '65 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth's Story Superbly Told

February 1965 By ALBERT I. DICKERSON '30 -

Article

ArticleThe Battle of the Non-Teachers

February 1965 By M. DANIEL SMITH '46

Features

-

Feature

FeatureOnward and Upward with '68

NOVEMBER 1964 -

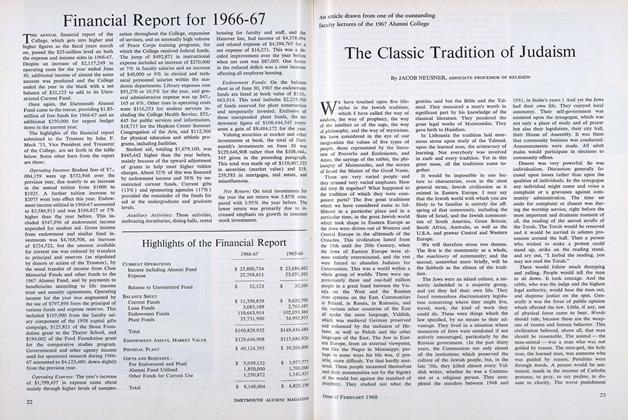

Feature

FeatureThe Classic Tradition of Judaism

FEBRUARY 1968 By JACOB NEUSNER -

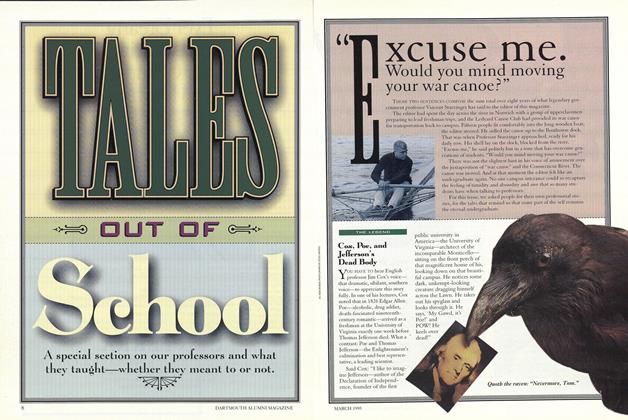

Cover Story

Cover StoryCox, Poe, and Jefferson's Dead Body

MARCH 1995 By Peter Gilbert '76 -

Feature

FeatureStudent Activism at Dartmouth

MAY 1966 By RICHARD A. BATHRICK '66 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO READ A POET

Sept/Oct 2001 By ROBERT FROST -

Feature

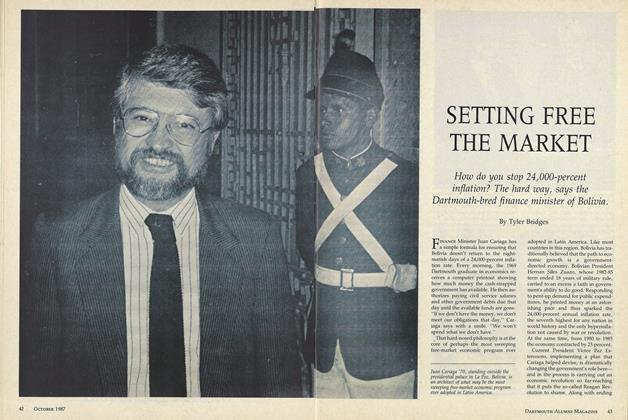

FeatureSETTING FREE THE MARKET

OCTOBER • 1987 By Tyler Bridges