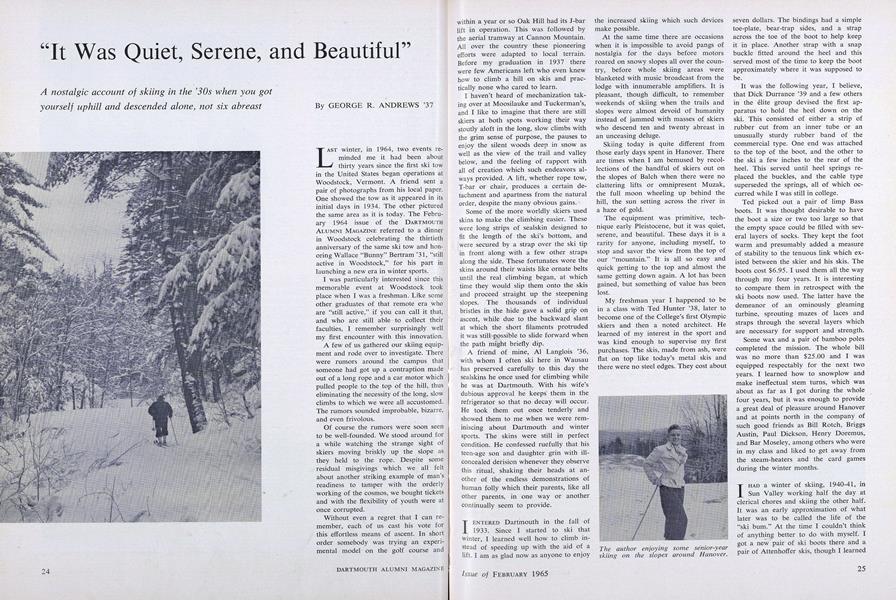

A nostalgic account of skiing in the '30s when you gotyourself uphill and descended alone, not six abreast

LAST winter, in 1964, two events reminded me it had been about •J thirty years since the first ski tow in the United States began operations at Woodstock, Vermont. A friend sent a pair of photographs from his local paper. One showed the tow as it appeared in its initial days in 1934. The other pictured the same area as it is today. The February 1964 issue of the DARTMOUTH ALUMNI MAGAZINE referred to a dinner in Woodstock celebrating the thirtieth anniversary of the same ski tow and honoring Wallace "Bunny" Bertram '31, "still active in Woodstock," for his part in launching a new era in winter sports.

I was particularly interested since this memorable event at Woodstock took place when I was a freshman. Like some other graduates of that remote era who are "still active," if you can call it that, and who are still able to collect their faculties, I remember surprisingly well my first encounter with this innovation.

A few of us gathered our skiing equipment and rode over to investigate. There were rumors around the campus that someone had got up a contraption made out of a long rope and a car motor which pulled people to the top of the hill, thus eliminating the' necessity of the long, slow climbs to which we were all accustomed. The rumors sounded improbable, bizarre, and even frivolous.

Of course the rumors were soon seen to be well-founded. We stood around for a while watching the strange sight of skiers moving briskly up the slope as they held to the rope. Despite some residual misgivings which we all felt about another striking example of man's readiness to tamper with the orderly working of the cosmos, we bought tickets and with the flexibility of youth were at once corrupted.

Without even a regret that I can remember, each of us cast his vote for this effortless means of ascent. In short order somebody was trying an experimental model on the golf course and within a year or so Oak Hill had its J-bar lift in operation. This was followed by the aerial tramway at Cannon Mountain. All over the country these pioneering efforts were adapted to local terrain. Before my graduation in 1937 there were few Americans left who even knew how to climb a hill on skis and practically none who cared to learn.

I haven't heard of mechanization taking over at Moosilauke and Tuckerman's, and I like to imagine that there are still skiers at both spots working their way stoutly aloft in the long, slow climbs with the grim sense of purpose, the pauses to enjoy the silent woods deep in snow as well as the view of the trail and valley below, and the feeling of rapport with all of creation which such endeavors always provided. A lift, whether rope tow, T-bar or chair, produces a certain detachment and apartness from the natural order, despite the many obvious gains.

Some of the more worldly skiers used skins to make the climbing easier. These were long strips of sealskin designed to fit the length of the ski's bottom, and were secured by a strap over the ski tip in front along with a few other straps along the side. These fortunates wore the skins around their waists like ornate belts until the real climbing began, at which time they would slip them onto the skis and proceed straight up the steepening slopes. The thousands of individual bristles in the hide gave a solid grip on ascent, while due to the backward slant at which the short filaments protruded it was still possible to slide forward when the path might briefly dip.

A friend of mine, Al Langlois '36, with whom I often ski here in Wausau has preserved carefully to this day the sealskins he once used for climbing while he was at Dartmouth. With his wife's dubious approval he keeps them in the refrigerator so that no decay will occur. He took them out once tenderly and showed them to me when we were reminiscing about Dartmouth and winter sports. The skins were still in perfect condition. He confessed ruefully that his teen-age son and daughter grin with ill-concealed derision whenever they observe this ritual, shaking their heads at another of the endless demonstrations of human folly which their parents, like all other parents, in one way or another continually seem to provide.

I ENTERED Dartmouth in the fall of 1933. Since I started to ski that winter, I learned well how to climb instead of speeding up with the aid of a lift. I am as glad now as anyone to enjoy the increased skiing which such devices make possible.

At the same time there are occasions when it is impossible to avoid pangs of nostalgia for the days before motors roared on snowy slopes all over the country, before whole skiing areas were blanketed with music broadcast from the lodge with innumerable amplifiers. It is pleasant, though difficult, to remember weekends of skiing when the trails and slopes were almost devoid of humanity instead of jammed with masses of skiers who descend ten and twenty abreast in an unceasing deluge.

Skiing today is quite different from those early days spent in Hanover. There are times when I am bemused by recollections of the handful of skiers out on the slopes of Balch when there were no clattering lifts or omnipresent Muzak, the full moon wheeling up behind the hill, the sun setting across the river in a haze of gold.

The equipment was primitive, technique early Pleistocene, but it was quiet, serene, and beautiful. These days it is a rarity for anyone, including myself, to stop and savor the view from the top of our "mountain." It is all so easy and quick getting to the top and almost the same getting down again. A lot has been gained, but something of value has been lost.

My freshman year I happened to be in a class with Ted Hunter '38, later to become one of the College's first Olympic skiers and then a noted architect. He learned of my interest in the sport and was kind enough to supervise my first purchases. The skis, made from ash, were flat on top like today's metal skis and there were no steel edges. They cost about seven dollars. The bindings had a simple toe-plate, bear-trap sides, and a strap across the toe of the boot to help keep it in place. Another strap with a snap buckle fitted around the heel and this served most of the time to keep the boot approximately where it was supposed to be.

It was the following year, I believe, that Dick Durrance '39 and a few others in the elite group devised the first apparatus to hold the heel down on the ski. This consisted of either a strip of rubber cut from an inner tube or an unusually sturdy rubber band of the commercial type. One end was attached to the top of the boot, and the other to the ski a few inches to the rear of the heel. This served until heel springs replaced the buckles, and the cable type superseded the springs, all of which occurred while I was still in college.

Ted picked out a pair of limp Bass boots. It was thought desirable to have the boot a size or two too large so that the empty space could be filled with several layers of socks. They kept the foot warm and presumably added a measure of stability to the tenuous link which existed between the skier and his skis. The boots cost $6.95. I used them all the way through my four years. It is interesting to compare them in retrospect with the ski boots now used. The latter have the demeanor of an ominously gleaming turbine, sprouting mazes of laces and straps through the several layers which are necessary for support and strength.

Some wax and a pair of bamboo poles completed the mission. The whole bill was no more than $25.00 and I was equipped respectably for the next two years. I learned how to snowplow and make ineffectual stem turns, which was about as far as I got during the whole four years, but it was enough to provide a great deal of pleasure around Hanover and at points north in the company of such good friends as Bill Rotch, Briggs Austin, Paul Dickson, Henry Doremus, and Bar Moseley, among others who were in my class and liked to get away from the steam-heaters and the card games during the winter months.

I HAD a winter of skiing, 1940-41, in Sun Valley working half the day at clerical chores and skiing the other half. It was an early approximation of what later was to be called the life of the "ski bum." At the time I couldn't think of anything better to do with myself. I got a new pair of ski boots there and a pair of Attenhoffer skis, though I learned little more about skiing than I did at Dartmouth.

One weekend there I encountered Dave Bradley '38. He was out racing in the Harriman Cup events. To my surprise he told me he was in medical school. I remembered him for his writing prowess as well as his skiing ability, so I was particularly struck that he was becoming a physician also. I was envious of such varied talents and of such a sensible, creative approach to life. Somewhat to my astonishment as well as to that of others, I later became a physician myself, more specifically a psychiatrist.

It is difficult to realize these days that I am one of the oldest skiers on the hill. There are still some who have a little seniority, but they are dropping off like flies. While there are seven Dartmouth graduates in and about the environs of Wausau, only Dunbar Schuetz '42, Al Langlois '36, and myself take to skis in the winter, so far as I am aware.

While skiing has always been the most enjoyable sport I know, it has also been singularly refractory to all my attempts through the years to master it. On a tendegree incline with an excellent base and two inches of powder, I can convey even at this advanced age to the eyes of infants and non-skiers the impression of a certain skill. But as soon as the more demanding slopes are encountered the old habits assert themselves with complete authority. I am back on my heels, leaning into the slope, closely resembling a beginner on his second hour of skiing. I know, and yet hate to admit it even at this late date, that I apparently was never really intended to be a skier. Yet as predictable as spring is the thought at the end of each season that next year I really will get the hang of it. It is the recurrent fantasy of all the duffers in every sport who love it but never actually achieve mastery.

One of the grimly amusing problems for people like myself who learned the rotation techniques is trying to unlearn this in favor of the counter-rotation method in which apply principles just the opposite of those deeply ingrained in every cell, muscle, tendon, and neurone. One of the greatest threats to the mental balance of a man of 45 to 50 is trying to come down a slope turning the shoulders contrary to the direction of the turn instead of into it as in the past.

Acute depressions, temporary psychotic episodes, and even hysterical paralyses are common in such people as they lurch down the slopes muttering instructions to their contrary extremities, trying vainly to overcome the habits of a lifetime. Probably my greatest usefulness in the Ski Patrol is in dealing with these seriously troubled personalities. There is really no cure for them since few ever manage to pick up the new skiing principles, and yet they all quite pathetically insist, just as I do, on coming back year after year in the futile attempt to achieve the impossible.

A few hours on the couch, a judicious use of one of the tranquilizers, and perhaps a sedative to still the agonized struggling and crying out during the night prove effective in the majority of cases. A few have to give up skiing altogether to preserve their sanity.

Of course there are also fractures and sprains to be splinted and carried down by toboggan to the first-aid station, and thence to the hospital. I often wonder what happened to the hapless souls who sustained such injuries in the years before the Ski Patrol was founded in 1937. What agonies there must have been getting an injured skier down from Tuckerman's Ravine to the base, and thence to some nearby hospital or doctor's office.

Just thinking of it now staggers the imagination. But at the time we were all climbing and skiing around New England before 1937 the thought of such a contingency never even seemed to cross our minds. I don't even recall encountering anyone with an injury during my college years of skiing, though doubtless there must have been some, even with the hardier breed which typified that heroic era.

The only time I ever got hurt on skis I wasn't even moving. I was just standing and looking down into the Vale of Tempe, wondering if I could take it straight. My skis slipped, and I fell, catching a pole under me and twisting my left arm so that the shoulder was dislocated. Somehow I got down to the hospital, had the dislocation reduced, but with the usual foolishness of youth was almost immediately skiing again, the arm in a sling.

Locally the closest equivalent to the picture of the Woodstock area in 1934 contrasted to the same in 1964 is a collection of photographs of some of us skiing around Hanover as we were then, tanned, slender, coolly smiling, with full heads of hair. The mirror provides the 1965 contrast after the ski cap, the goggles, and the jacket have been taken off. I still feel a start of surprise when I see this aging stranger peering out at me.

Outside of this, the woods, the snow, the exhilaration of descent have not changed. They still work their timeless magic, illustrating every winter the classic statement that Dartmouth's famous ski coach Otto Schniebs used to make when he would say: "Gentlemen, skiing is not just a shport. It is a vay of life."

The author enjoying some senior-yearskiing on the slopes around Hanover.

Paul Dickson '37, the author's classmateand skiing companion, executing the rotation technique of yesteryear.

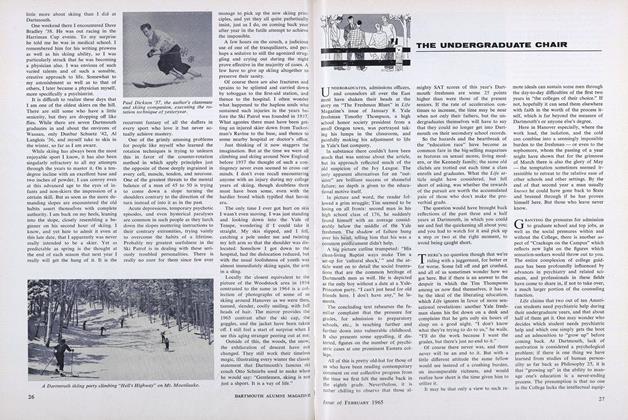

A Dartmouth skiing party climbing "Hell's Highway" on Mt. Moosilauke.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA NEW BREED OF CHUBBER

February 1965 By JOHN ALDEN THAYER JR. '65 -

Feature

FeatureBusiness Still Draws Its Share of Graduates

February 1965 By ADDISON L. WINSHIP '42 -

Feature

FeatureFreshman-Sophomore Curriculum Revised

February 1965 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

February 1965 By BOB WILDAU '65 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth's Story Superbly Told

February 1965 By ALBERT I. DICKERSON '30 -

Article

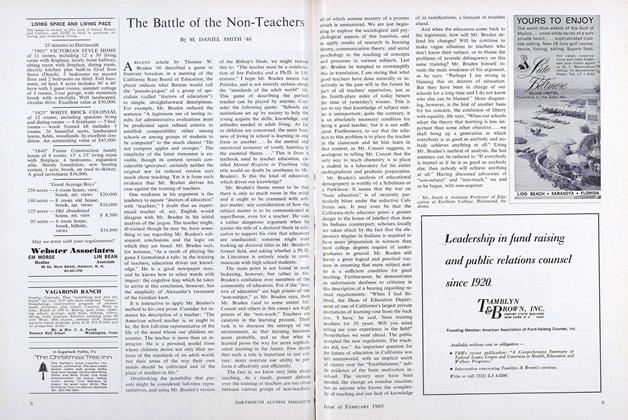

ArticleThe Battle of the Non-Teachers

February 1965 By M. DANIEL SMITH '46

GEORGE R. ANDREWS '37

Features

-

Feature

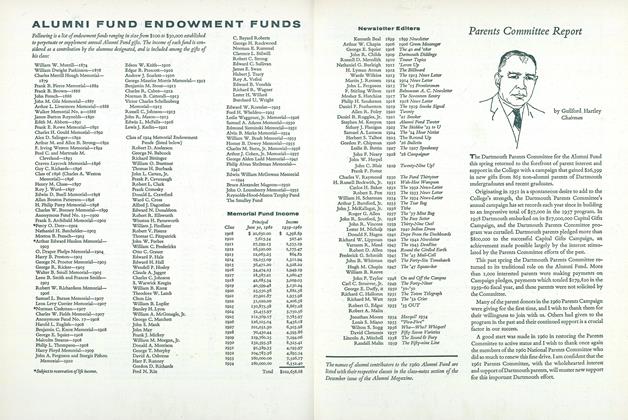

FeatureALUMNI FUND ENDOWMENT FUNDS

December 1960 -

Feature

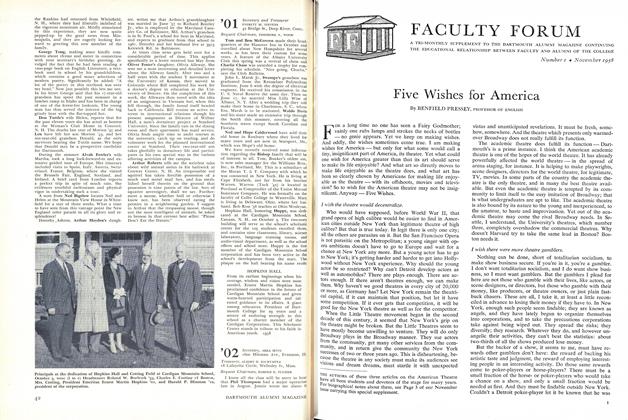

FeatureFive Wishes for America

By BENFIELD PRESSEY -

Feature

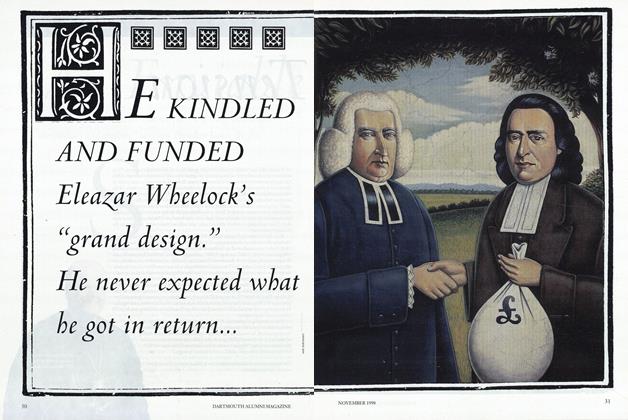

FeatureThe Betrayal Of Samson Occom

NOVEMBER 1998 By Bernd Peyer -

Cover Story

Cover StoryI Dance for Me

APRIL 1997 By Elizabeth Carey '93 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryYou Thougnt Rotc was Dead?

November 1994 By Frederic J. Frommer -

Feature

FeatureThe Mystery of the Tao

NOVEMBER 1998 By Rebecca Bailey