By Leonard W. Doob '29. NewHaven, Conn.: Yale University Press,1964. 297 pp. $6.75.

In this volume, Professor Doob takes the reader through the labyrinth of historical, sociological, and psychological thinking concerning the often used but rarely specified concepts, "patriotism" and "nationalism." His own definitions shape the general structure of the book: "patriotism" is defined as "the more or less conscious conviction of a person that his own welfare and that of the significant groups to which he belongs are dependent upon the preservation or expansion (or both) of the power and culture of his society"; "nationalism" is seen as "the set of more or less uniform demands (1) which people in a society share, (2) which arise from their patriotism, (3) for which justifications exist and can readily be expressed, (4) which incline them to make personal sacrifices in behalf of their government's aims, and (5) which may or may not lead to appropriate action."

Although such definitions may seem initially overcomplex, especially in the face of the frequency with which the concepts are used in today's news transmission, political conversation, and historical speculation, it is precisely this complexity which is too often overlooked, thus leading to confusion and misunderstanding. The need for such definitional elaboration is supported by the author, both with the data which he quotes from his voluminous set of references, and from that which he supplies from his own research in the South Tyrol and Africa.

In the development of his thesis, he considers the importance of such factors as the "basic ingredients" of the concepts — the land, the people, and the culture from which they spring; the impact of the media of communication available; the perception of the attributes of a group by its members — its traits and potentialities; the group's ego — and ethnocentric evaluations. Professor Doob also devotes attention to the matter of patriotic convictions, their origins, development, and maturity in a "patriotic personality, " and to the many justifications which national and cultural groups offer to support their attitudes. This justification process will perhaps be of greatest interest to those of a social psychological turn of mind. They range from the absolutistic — "... we are following His will" to the personificative — "We are a family . ..." In all, Doob discusses and gives instances of 23 classes of justification and, in what is perhaps the most intriguing part of the book, supplements his earlier examples with a "content analysis" of several important historical documents (e.g., Wilson's Fourteen Points. the various World War II declarations, the preamble to the NATO Treaty, and the United Nations Charter) indicating with devastating frequency the ways in which essentially identical phrases are used in the name of justifying either war or peace.

It is the rare social theorist who goes against the tide and suggests that what appear as simple, usable concepts are really loaded with so much surplus meaning that they serve to hinder rather than help communication — the more common attempt is to seize such concepts and endeavor to simplify the complex social phenomena of our day. Professor Doob deserves credit for both his initiative and convincing skill.

Assistant Professor of Psychology

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

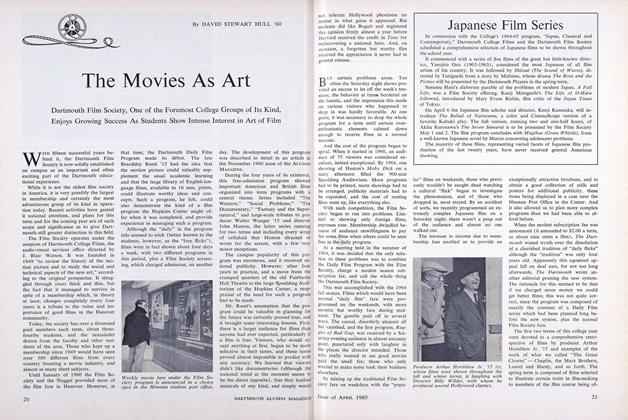

FeatureThe Movies As Art

April 1965 By DAVID STEWART HULL '60 -

Feature

FeatureEB's EDITOR

April 1965 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

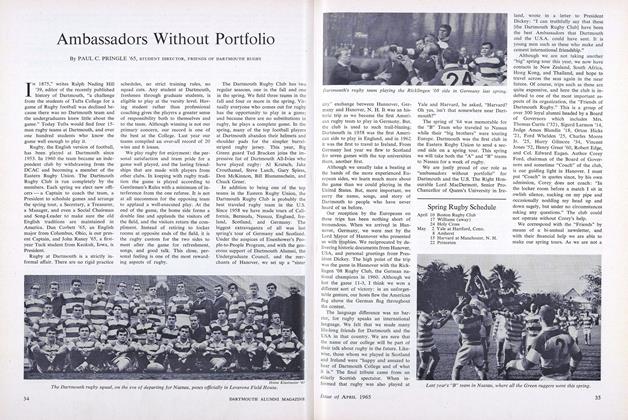

FeatureAmbassadors Without Portfolio

April 1965 By PAUL C. PRINGLE '65 -

Feature

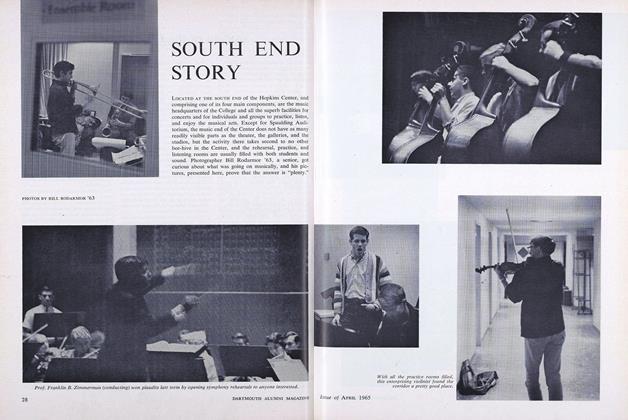

FeatureSOUTH END STORY

April 1965 -

Article

ArticleWITH THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

April 1965 By ERNIE ROBERTS -

Article

ArticleLove-Letter to a College

April 1965 By A NEW ASSISTANT PROFESSOR

LLOYD H. STRICKLAND

Books

-

Books

BooksA SALESMAN TAKES AN INTEREST.

April 1953 By Albert W. Frey '20 -

Books

BooksTHE DAMNED WEAR WINGS.

By HERBERT W. WEST '22 -

Books

BooksMOUNT WASHINGTON REOCCUPIED

December 1933 By N. L. G. -

Books

BooksTHE ESSAY: A CRITICAL ANTHOLOGY

July 1952 By Robert S. Kinsman '40 -

Books

BooksTHE SUMMER I WAS LOST.

JULY 1965 By ROBERT S. MONAHAN '29 -

Books

BooksTHE MISSISQUOI LOYALISTS

October 1938 By W. R. Waterman