By Leonard W. Doob '29. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1960. 333 pp. $6.00.

In the research reported in this volume Professor Doob has departed from the more customary approaches to the study of acculturation among less-civilized societies. He has not encumbered himself with the lengthy, and perhaps inaccurate, regress so often encountered with the historical explanation of "how they got this way"; nor has he entered the scene fully committed to a theoretical orientation to find, 10 and behold, that his data "fit the model." He has instead attempted to take an objective look at what happens to people as they exchange more primitive modes of behavior for new. A series of hypotheses about this process of change are ventured; and, since his own primary data are gathered from four societies which can be roughly ordered by the degree to which they have adopted European behaviors, the author is in a position to make more comprehensive comparisons than are often possible.

These hypotheses are of three types, and each deserves illustration. First, there are causal hypotheses, which are attempts to specify why, in the process of becoming more civilized, members of a society learn certain forms of new behavior but not others. For example: "People who are confronted with alternative beliefs and values are likely to retain traditional ones which appear to serve a continuing need and reject those which do not, but always to retain some of the traditional views" (p. 150). In comparing those members of three African cultures who have had formal education in Western schools (the most discriminating and operationally consistent index of acculturation) with those who have not, Doob demonstrates significant differences in overall "traditionalism." The changing groups appear to reject many traditional views, yet as many as 26% of the highly "educated in one tribal culture endorse strange, but still functional, beliefs such as "Some stones can talk."

The second class of hypotheses are consequential - they suggest consequences of the civilization process. In illustration: "People changing centrally from old to new ways are likely to become more tolerant of delay in the attainment of goals" (p. 88). This hunch is based in part on the observations of other researchers, who were concerned with differential orientation toward the future of children from different socioeconomic groups in the United States. In the present context, Doob finds that well-educated Africans and Jamaicans are more likely than the poorly educated to plan for the future, to report specifically how a windfall would be spent, to anticipate what their lives would be like in five years, etc.

Finally, many of the hypotheses are interactional, so termed because their author recognizes the not-infrequent methodological difficulty of separating effect from cause. In support of the hypothesis: "In comparison with those who remain unchanged or who have changed, people changing from old to new ways are likely to be generally sensitive to other people." (p. 135), Doob reveals that the highly educated, rather than the poorly educated, are more likely to (a) try to avoid unpopularity, (b) claim preference for the group, not the individual, and (c) want people to behave decently for "social" reasons. However, the poorly educated are more likely to give an ambiguous response (if, indeed, any) to projective pictures such as those designating a chief and one of his subjects, or a European and an African, and asked, "What are the people doing?"

The reviewer would be unfair to the author were he to imply that all of the hypotheses aroused as much curiosity, or were as strongly supported by the data, as these examples. Yet, in this context, to be commended especially are (a) the author's adherence to his stated purpose:

... to formulate a set of hypotheses which claim little originality; to use the hypotheses as principles to sharpen our perception and to organize sampies of existing research; to explore problems whose importance, at a time when "underdeveloped" areas are at the tip of political, economic and philanthropic tongues, can scarcely be questioned; and, hence, at the very minimum, to provide a target - or many targets - which better marksmen and better ammunition in the future will hit more effectively (p. xi); (b) the painstaking description of the sam- pling procedures, methodology, and analy- sis of psychological test and interview data; (c) the presentation of supplementary data from studies of Middle Eastern communi- ties and American Indian tribes, gleaned from the results of other investigators and pertinent to many of the hypotheses; and (d) his emphasis on quantitative data, "... no matter how trivial or even statistically unconvincing, not because they lead rapidly to Wisdom but because they suggest the need for precision if better truths are to be discovered" (p. xi).

There is little doubt in this reviewer's mind that this "psychological exploration" will prompt considerable research activity. One can hope that it will be as carefully conducted and as competently reported as Professor Doob's.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Dollop of Yankee Talk

February 1961 -

Feature

FeatureCampus Cosmopolitans

February 1961 -

Feature

FeatureNow They're Flicks, Not Movies, But The Nugget Still Carries On

February 1961 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

FeatureDr. Myron Tribus of UCLA Named Dean of Thayer School

February 1961 -

Feature

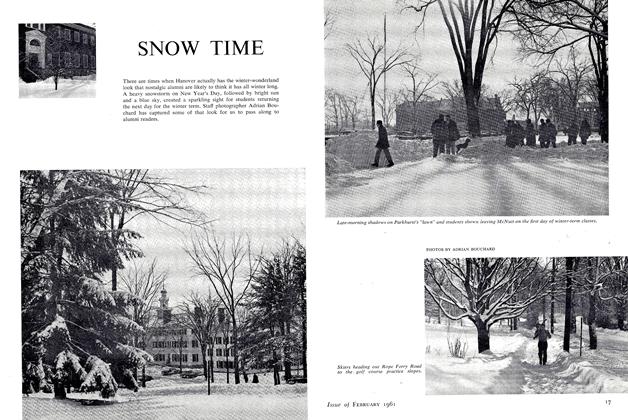

FeatureSNOW TIME

February 1961 -

Article

ArticleProblems of Land Development in the New African Nations

February 1961 By BARRY N. FLOYD,

LLOYD H. STRICKLAND

Books

-

Books

BooksTHE LUSTY TEXANS OF DALLAS

March 1951 By ALLEN R. FOLEY '20 -

Books

BooksFRENCH COMME 1L FA UT.

February 1935 By Charles R. Bagley -

Books

BooksALUMNI PUBLICATIONS

April, 1923 By F. E. BROWN. -

Books

BooksPRINCIPLES OF ASTRONOMY.

JANUARY 1965 By GEORGE Z. DIMITROFF -

Books

BooksSELECTED WRITINGS OF OSCAR WILDE.

JUNE 1969 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksELECTRICAL SYSTEMS DESIGN.

June 1957 By RAYMOND F. MOSHER