FRATERNITIES will be dropped at Amherst College if the recent recommendations of a special Subcommittee to Study Student Life are accepted by the faculty, administration, and trustees of that institution. While we cannot glibly call the proposed changes there a "foregone conclusion," the subcommittee's report is so compellingly presented that the college would be flying in the face of its own best critics in rejecting it.

Fraternities are always a touchy subject these days, for reasons that the Amherst group has well understood. Its 23-page report, distributed this winter to all faculty, students, alumni, and parents, is introduced by a letter from President Calvin H. Plimpton which stresses that its proposals will have to be treated by a larger committee before they can even be submitted for final adoption.

The active fraternity member who opens the pamphlet looks for the "bad news" on the first page, and becomes suspicious when the word "fraternity" is not even mentioned in the first 1800 words of the text. It may take him a second reading of the whole report before he realizes that this arrangement is no evasion of an unpleasant task. It is rather the clearest possible exposition of an unusually sensitive analysis of the student situation. The subcommittee begins at the beginning and proceeds, through a faultless chain of reasoning, toward a set of conclusions that are unavoidable from the faculty point of view. The only way in which the whole argument could be refuted would be to take exception with this viewpoint, which is probably best summarized in the state- ment: "A liberal arts college ... should be more civilized than the world in which it exists or the members of which it is composed, yet relevant enough to its world and its members to be actively civilizing."

Even the study on which the report is based did not spring out of a spontaneous desire to shake foundations. Amherst's Committee on Educational Policy formed the subcommittee when it decided that "the quality of the curriculum cannot be considered apart from the quality of the life of the students who experience it." The key word in the relationship between the two is relevance, and the essential conclusion of the study is that the institution of fraternities is no longer relevant "to the aims of an educational community."

Between the premises and the big conclusion, the report looks into the whole problem of intellectual values in undergraduate life, and comments in terms that sound like nothing so familiar as Dartmouth UGC President Weber's convocation speech last September. It sees the freshman often disappointed in his expectation of college life as a "Grand Intellectual Adventure," burdened with more work than he can do his best on, and frustrated by the competition. Then, "he may discover some relief in deliberately refusing to compete, trying to get by with a series of selected minimal efforts at crucial moments. Having been taught to see the life of the mind as a game whose goal is grades, he may discover an alternative game at which he can be more successful, called Beating the System ... [thus scorning] the very values that brought him to [college] in the first place."

The connection of all this to the fraternity question is not immediately obvious. But the essence of what the Com- mittee on Educational Policy, and the Subcommittee on Student Life, are trying to achieve is a new realization of those values which are so often trampled in the race. They recognize that when the pressure abates, "relaxed moments found or made during a day, or a semester, are understandably used for recuperation, not further exploration." But what follows is the tendency to separate thought and pleasure, which undercuts the principles of liberal education. The subcommittee emphasizes that it is not their purpose to make the students engage in more "intellectual" or more "useful" pursuits. What they idealize is the college in which "a student found distinctions between sorts of activities irrelevant, where he could say not 'I am working now' or 'I am playing now,' but 'I am living my own life.' " They recognize their own idealism, however, and they add, "Perhaps an attempt to oppose a direction that is an inescapable part of American life is quixotic, but we are convinced that it is the obligation of the college community at least to refrain from reinforcing such a tendency."

What follows, in short, is the conclusion that the fraternities have helped to reinforce the tendency, by limiting "the ways in which a student encounters the formal disciplines of his education." The subcommittee members "assume that a student will discover that he has more significant autonomy, privacy, and freedom in setting the tone of his social and intellectual life if he is freed from some of the time- and spirit-consuming obligations to separate groups whose relevance to the aims of an educational community is not clear."

As recently as 1957 a faculty committee had recommended the continuation of fraternities at Amherst, but had added a section to its report suggesting circumstances ("ten years from now") in which they might better be eliminated. Only eight years have gone by, but many of the conditions have been realized: the college is expanding, new dorms have been built, and several fraternities are in trouble. In addition, the "total opportunity" system under which every upperclassman can be guaranteed a bid from a fraternity recently began to break down, as it had at Williams. In 1963-64, only 74 per cent of eligible students were active members.

What the present subcommittee is recommending is a system of residential units — called "societies" — around which most extracurricular student life would be organized. The new units would incorporate combinations of former fraternity buildings and regular college dormitories. Each would include facilities for social life, study, and recreation, and each might contain certain facilities not found in the others: a game room, music rooms, a little theater, art studio, or photographic darkroom. Incoming freshmen would read short descriptions of each society, and list four choices, but final assignments would be made by the college. Students could apply for changes after the first year.

The relevance of Amherst's decision is sure to be variously interpreted here at Dartmouth. To begin with, the fraternity structure at Amherst is very different from ours: even though they housed only 36 per cent of all undergraduates last year, the fraternities still effectively organize the entire campus. On the other hand, Amherst's greater proximity to women's colleges means a regular social life for which the societies may prove a more comprehensive setting. Amherst is just enough closer than Dartmouth to the mainstreams of inter-urban traffic to be sure of being able to provide enough fresh contact with "the world outside." To acknowledge that a gap exists here would be far from offering ways to fill it.

But in most of the Amherst report, one could substitute the name of Dartmouth without altering in the slightest its eloquent truth. No one here connected with the fraternity system doubts that we will be facing some of the same challenges. We will have to decide whether it is in the nature of fraternities to demand better of ourselves, or whether any amount of good intentions can overcome the urge-to-escape which fraternities satisfy. When it comes, the debate will hopefully be conducted in terms of exciting new forms; coeducation will also be mentioned.

The subcommittee at Amherst wrote that the greatest difficulty was in "breaking through the stale cycle of arguments which has hitherto trapped us all." We have yet to make that break, and for us it might be an even bigger one. There is still a comforting warmth in the stateness, and with the success of a program like the Cutter-North Experiment we can be satisfied with ourselves a while longer. But if it is true that fraternities chiefly serve to maintain the thoughtpleasure dichotomy, and thus act mainly as a distraction, then we will never know what dorm life might become.

If we in the system feel uneasy looking ahead, it is probably because we realize the gap separating what we want and what we ought to want. The hope would be that our real fulfillment lies between.

Rushing the Season: Warm sun in early March was more than some could resist.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

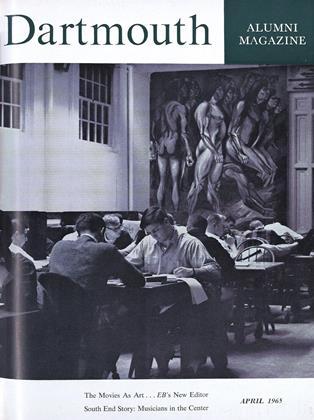

FeatureThe Movies As Art

April 1965 By DAVID STEWART HULL '60 -

Feature

FeatureEB's EDITOR

April 1965 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

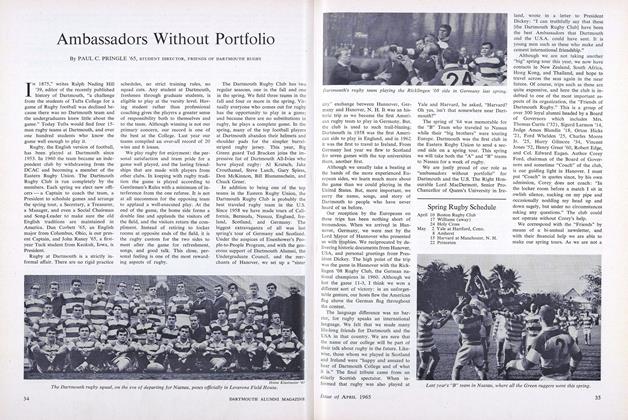

FeatureAmbassadors Without Portfolio

April 1965 By PAUL C. PRINGLE '65 -

Feature

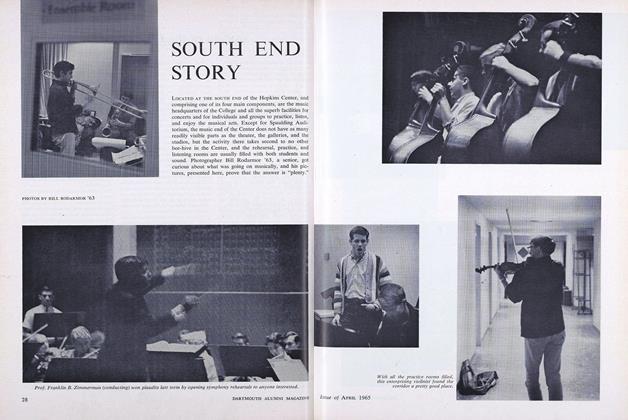

FeatureSOUTH END STORY

April 1965 -

Article

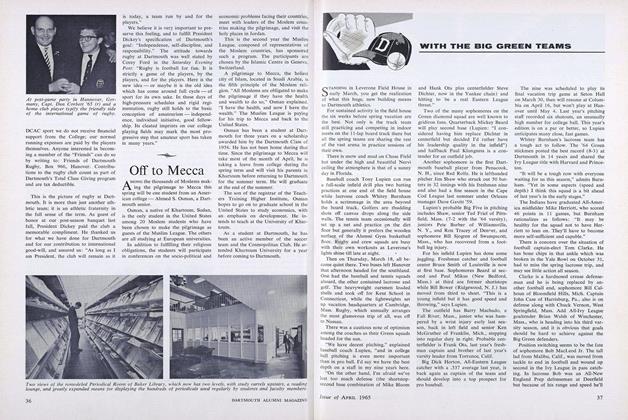

ArticleWITH THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

April 1965 By ERNIE ROBERTS -

Article

ArticleLove-Letter to a College

April 1965 By A NEW ASSISTANT PROFESSOR