Edited by Prof. ClydeE. Dankert (Economics), Floyd C. Mann,and Herbert R. Northrup. New York:Harper and Row, 1965 . 208 pp. $3.50.

The eleven essays in this volume present a summary evaluation of the findings of social scientists on the relationship between hours of work and the general welfare. The essays were written during a period of substantial unemployment when agitation for the shorter work-week and for curbs on the use of overtime was at its height. They were published, on the other hand, at a time when continuing improvements in the employment situation and the prospect of stepped-up defense expenditures had reduced the pressures for hours' limitations and were diverting public attention to the more immediate problem of coping with inflation. It is to the credit of the editors that this shift in policy issues has not diminished the value or relevance of the work reviewed here; for while the efficacy of a shorter-hours policy serves as the focus or organizing theme for several of the essays, every effort has been made to ensure that other aspects of the hours-of-work question were not neglected.

The essays cover a wide variety of topics, ranging from the forces that affect hours-of-work practices to the influence of changes in such practices on individual and social welfare. They reveal, for example, how labor historians interpret the role of collective bargaining and legislation in regulating time spent at work, what sociologists and others have discovered about the effects of shift work and multiple job holding on the social, psychological, and physical health of workers, and why economists are generally opposed to hours' restrictions as a means of coping with the problems of cyclical and structural unemployment. The reader will find, of course, that many of the issues raised are not wholly resolved, that significant gaps exist in our understanding of hours-of-work phenomena. This is not the fault of the authors, who for the most part have handled their assignments competently. Nor is it necessarily the fault of social scientists generally. One wonders, however, why the possibilities that have long existed for systematic study in this area have not been more aggressively exploited; for unlike many other fields of social inquiry, the hours-of-work field offers abundant opportunities for empirical research. The present volume identifies the need; it is to be hoped that scholars in the area will accept the challenge.

Professor of Business EconomicsTuck School

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

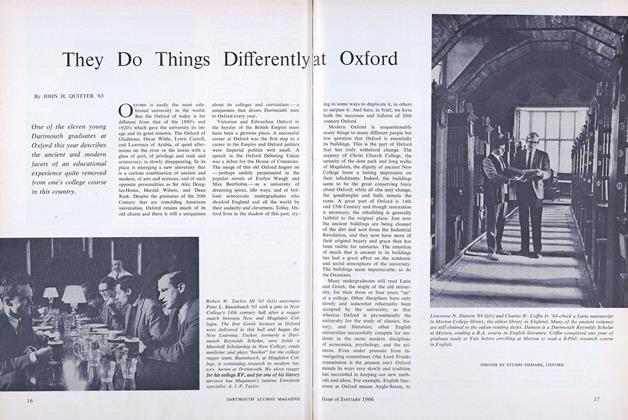

FeatureThey Do Things Differently at Oxford

January 1966 By JOHN H. QUITTER '63 -

Feature

FeatureDid Webster Really Say It?

January 1966 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Feature

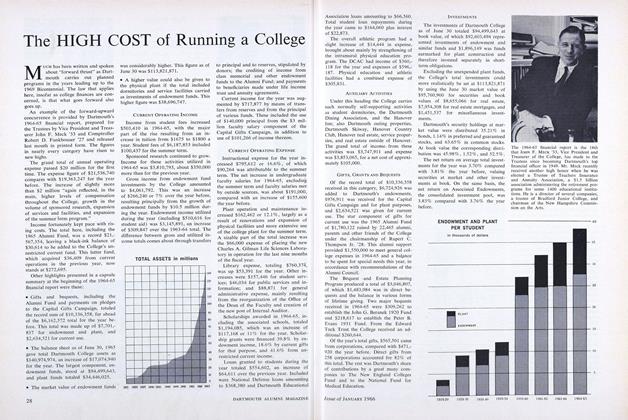

FeatureThe HIGH COST of Running a College

January 1966 -

Feature

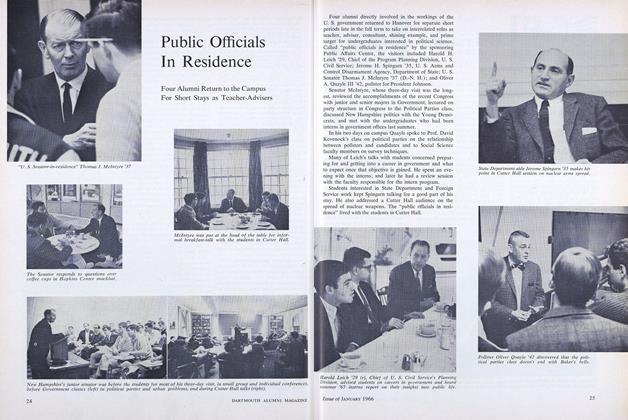

FeaturePublic Officials In Residence

January 1966 -

Article

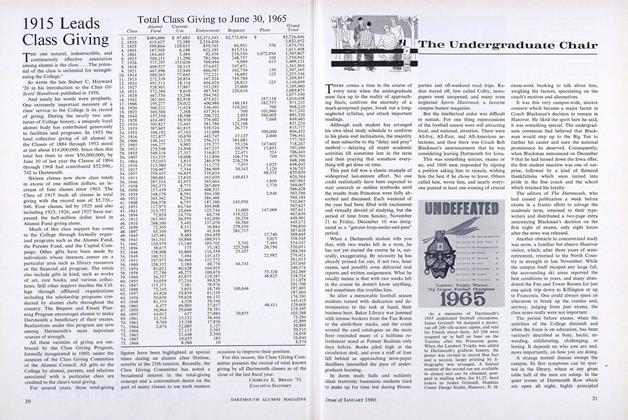

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

January 1966 By LARRY GEIGER '66 -

Article

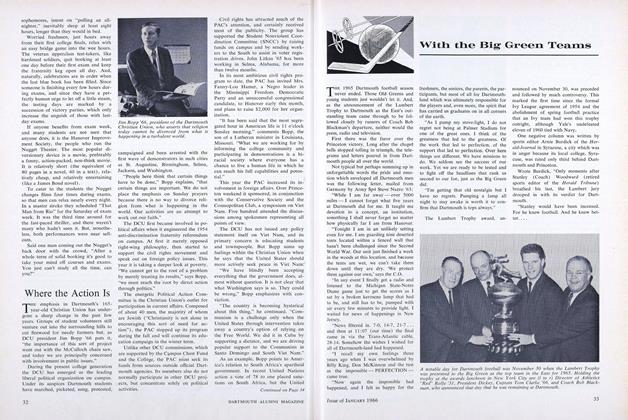

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

January 1966

ROBERT M. MACDONALD

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

April 1949 By DONALD G. MIX, ROBERT M. MACDONALD, ROGER C. WILDE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

March 1950 By DONALD G. MIX, ROBERT M. MACDONALD, ROGER C. WILDE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

November 1951 By REGINALD B. MINER, ROBERT M. MACDONALD -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

February 1954 By REGINALD B. MINER, ROBERT M. MACDONALD, DONALD G. MIX -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

March 1955 By REGINALD B. MINER, ROBERT M. MACDONALD, DONALD G. MIX -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

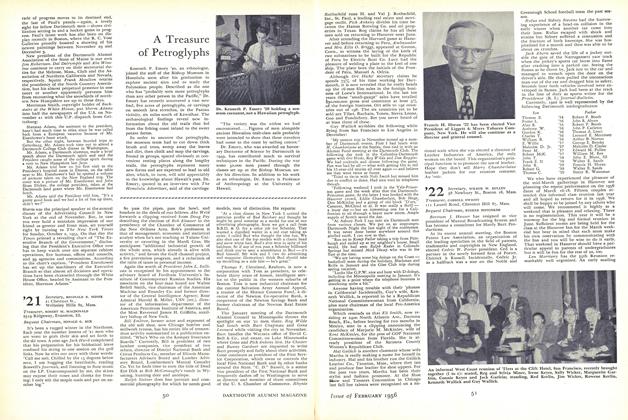

February 1956 By REGINALD B. MINER, ROBERT M. MACDONALD, DONALD G. MIX

Books

-

Books

BooksShelflife

Nov/Dec 2008 -

Books

BooksShelf life

Nov/Dec 2011 -

Books

BooksNEVER SAY DIET.

November 1954 By ALBERT I. DICKERSON '30 -

Books

BooksMRS. BRIDGE.

FEBRUARY 1959 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Books

BooksHISTORY OF GRANVILLE, MASSACHUSETTS.

March 1955 By NATHANIEL L. GOODRICH -

Books

BooksTHE GOLDEN STAR OF HALICH; A TALE OF THE RED LAND IN

NOVEMBER 1931 By W. R. Waterman