WITH more fervor than genius a Boston lawyer, Dartmouth '07, was once inspired to write a poem about Daniel Webster. In it he said that though he had never drunk wine before, he would drink nine toasts to Daniel Web- ster, "the giant of generations." Then, if still sober, he would drink one more toast to other Dartmouth men and to "the college on the hill."

Dwarfed by the immensity of the Webster colossus, however, the other Dartmouth men were soon forgotten; and the poet, flushed with the vision of what "Dear Dan," as he called him, meant to the upturned eyes of the nation, ended with a colloquial but none the less sincere apotheosis:

"With lips still wet I place the bet you are Dartmouth's biggest man." While not wishing to detract from Webster's glory, some thoughtful Dartmouth men long sometimes for a wider acquaintance with other Dartmouth sons -who matured in Hanover and contributed to American civilization. A list of eligible candidates may run longer than some unhistorically minded Dartmouth men might imagine.

In one standard biographical dictionary, Charles Ransom Miller, Dartmouth '72, gets only three lines indicating that he was born in 1849, died in 1922, and that he was an American journalist who had been on the staff of the Springfield (Mass.) Republican 1872-75' and The New YorkTimes 1875-1922 of which he was editor 1883-1922.

Such factual brevity hardly leads anyone to imagine the rich complexities and ramifications of the career of Charles Ransom Miller, son of a Hanover Center farmer. Even intuitive classmates would hardly have guessed how notable it was going to be. When a senior at Dartmouth Miller remarked that his chief ambition in life was to beat a certain young lady in croquet. He did. Incidentally she married him, and he went on to become the croquet champion of Great Neck, Long Island, where he lived and where he cultivated the impressive estate in Pineapple Lane now presided over with gracious modesty by his son, Hoyt Miller. But Charles Ransom Miller was more than a croquet player.

A wide reader as a senior, he was much too poor to have imagined the large library which he was going to build up in his own home and which made him known in New York as a sound scholar capable of arbitration on an international scale.

In Dartmouth classes of early days when the give-and-take of questions and answers was more pronounced than today, Miller, who needled professors so unmercifully that he was sometimes feared as much as he was admired, could hardly have foreseen that his Socratic method later would make him the friend of statesmen and the moulder of their policies. More, he became the intimate and adviser of Presidents.

If he was called to Washington to help shape national policies, he was just as much the organizer of newspaper attitudes that had profound effects on the public and on American history. When phoned by the New York Times office as late as 2 in the morning to receive an important piece of news, the former scatter-brained college senior could dictate at once with confidence and authority an impromptu editorial which would run without correction or emendation. Experienced journalists were amazed at the Miller grasp of fact and at the Miller delight in off-the-cuff allusions to Greek, Roman, and European

history. Undisciplined in preparatory school, Miller was expelled by Kimball Union Academy. Undisciplined in college, Miller was dropped by Dartmouth. His conduct on his return was so spotty that on graduation day he had to be hunted up, for he had feared that his sheepskin would be withheld at the last moment. Academically rebellious, he refused to buy textbooks for his courses, yet later he became a champion of the liberal college as a preparation for life and wrote to President Hopkins that one of his bitterest disappointments was that he could not fulfill an ardent ambition of long standing, to attend his fiftieth reunion.

Often irresponsible when a Dartmouth student about running up bills, Charles Ransom Miller as Editor of The Times paid sufficient attention to his finances to die a millionaire after a luxurious and expansive life. Wealth was delightful, for he was so poor as a boy that he suffered torments because his stepmother forced him to wear home-made shirts, bleached linen in front but unbleached linen in back. This humiliation marked him in two ways. As a prosperous editor he never approved of the newspaper custom followed by reporters and editorial writers of working in their shirt sleeves, and he indulged himself in bureaus full of fancy shirts not only blue in color but also pink, all expensive.

Yet the Dartmouth of the late 60's and early 70's was no Vanity Fair. It was rather a burly world of unruly conformity with students giving the faculty a hard time. In the 1860's Dartmouth was easier to get into than Dartmouth in the 1950's. Chuck Miller did not have to present his record from KUA to a director of admissions. He went straight to the home of President Smith, who gave him three cards, one for the Latin professor (Parker), one for the Greek (Packard), and one for the mathematics (Quimby). After an oral examination each professor wrote a Greek hieroglyphic on his card and sent Chuck back to the president who made a gracious gesture that in one and the same motion symbolized congratulations, a promise of fellowship, and all the privileges and rights of the Class of 1872.

CHUCK MILLER found that with limitations Dartmouth lived up to its name as a liberal arts college. The wisest personal influence came from Professor

"Bully" Sanborn, then Evans Professor of Oratory and Belles Lettres, whose home was a happy refuge for students who found in it strong and conservative political and religious convictions. The beneficent influence of "Professor Bully" continues in hardly abated force today in the memorial to his name, Sanborn House, the brick building southwest of Baker Library, which has some thirty offices for members of the English Department.

Chuck Miller, however, found at Dartmouth neither a Baker nor a Sanborn. The library of that era was open only one hour a day. The catalogue was imperfect. Books could often not be found. The building had no heat. Students were refused direct access to the shelves. Students had got around faculty restrictions, however, by forming two collections of their own. The Social Friends and the United Fraternity libraries. The ingenious Chuck got himself appointed an aide to the student librarian, and as such he had free access at all times to all three libraries. Impressed with the omnivorousness of his reading, his classmates on graduation gave him a symbolic spade with an appropriate Latin inscription, an annual trophy going to the "digger" or, to change the metaphor, the burner of midnight oil. A prized heirloom, it now rests on Hoyt Miller's library table.

Miller's classmates gave him the honorary title of Spade because, the Aegis explained, he was "ye burner of ye midnight oil," a humorous exaggeration, for it was well known that he was incapable of letting his assignments interfere with anything he wanted at the moment particularly to do. The Dartmouth characterized him as "the most industrious (?) student" of the class, a "dig." When the Spade gave the customary speech of appreciation and thanks, the Aegis commented on it as"very fine and peculiarly fitting," probably an ironic reminder that in class he had been able to speak with similar eloquence but unhampered by facts or reason.

As rebel, Charles Miller turned to prose and more happily to poetry for a medium of expression which he found in the monthly publication, The Dartmouth, recently reestablished by the Class of 1867.

And as rebel, Charles Miller was influential in persuading his classmates to invite for the annual poetry reading a dismissed clerk in the U. S. Department of the Interior, Walt Whitman, whose Leaves ofGrass was a barbaric yawp against higher learning. That the Dartmouth Class of 1872 should have wished to affront New England conservatism and to give a violent blow to Sacred tradition was incomprehensible to the faculty. Yet there was nothing difficult to understand. Chuck Miller merely wanted to outrage professors. The same desire led him to express in classroom his inalienable belief in the opposite of most positions taken by them. It is hardly accurate to say that he was entirely indifferent to grades, for he entered with somevigor a contest with another future newspaperman of his class, John Bailey Mills, to see who would end up his college career at the bottom of the class. With journalistic flair, Chuck used to take French novels to classrooms to read while his classmates recited. Thus in the slang of the day he became "a beat," a gay dog who might even keep liquor under his bed, rather than "a seed," a sober, professor-fearing solemnside.

Conservative then as now, undergraduates shied away from inviting Chuck Miller, a non-conformist, to join a fraternity. The rebel responded not by sulking in his room or by behaving with ostentatious indifference. He himself founded a chapter, the Omicron Deuteron Chapter of Theta Delta Chi. With fitting pomp and fanfare, the President of the Grand Lodge came up from New York to officiate personally, and the first initiation took place in 17 Thornton Hall. Not long after, the first delegate to the annual convention of the fraternity in New York was conformist Charles Ransom Miller who had his first chance at sighting at first hand the city in whose destinies he later played so large a role.

Members of 1872 guessed what the world later discovered to be true, that Charles Ransom Miller had a brilliant mind with amazing powers of adaptability and concentration. Professor Quimby of the Mathematics Department fancied himself as a chess player and offered Miller a chance to learn the game with himself as instructor. Chuck told his classmates that with only this one lesson he could have beaten the professor but did not for fear of incurring his hostility. To make good his boast, Chuck under an assumed name entered a chess tournament by mail in which he knew Professor Quimby was competing and defeated him.

Bright though Charles R. Miller was, President Asa Dodge Smith and the Faculty condemned him as "an unworthy student" and dropped him from College at the end of the fall term of his sophomore year. Just what his offense was is no longer clear, but apparently his general cussedness got under professors' skins.

If a reader may believe what his eyes see in Charles Miller's own handwriting in his letter to the President, the experience was a major one, indeed even tragic.

"Respected Sir," he writes. . I waspained beyond expression. . . Yet he admitted that the punishment was just. He speaks of reform. "I am determined to profit by the past and live in earnest." The President's letter hangs "like a leaden weight" upon his heart.

"O God! I CANNOT BEAR THE THOUGHT that my mother must look down from Heaven upon the disgrace of her erring son, even though he never saw her face."

He assures the President that he can do the work and that he will be faithful. Readmission to College would mean readmission to life, "for I can see no way clear from the black Despair I shall feel if I am not taken back."

Then came the final plea. "O, will you not lend me a helping hand to be and todo better, to reform? I know Sir that you have a kind heart and if you will show kindness to me in my distress by using your influence with the Faculty to revert this sentence I can never be so ungrateful as to give you reason to regret it."

President Smith did have a kind heart and he did relent. Dropped from Dartmouth November 15, 1869, Charles Ransom Miller was readmitted on January 7, 1870. To the extent of applying himself, he kept his word and was graduated with his class a member of Phi Beta Kappa.

Before readmission he nearly starved trying to sell volumes of Mark Twain in the outside world, and then he found a job as typesetter in Tilton, New Hampshire.

But Charles Ransom Miller was too independent emotionally and intellectually t0 become, even with trying, an average and conventional student. His classmates viewed him askance. He was too unorthodox to be pigeonholed. Indeed they predicted for him little chance for financial success in life, but he became nonetheless one of the wealthiest men in the class. He gave five times as much to the Alumni Fund as the average gift, and even more. His holdings in The New York Times alone from an investment of $ 135,000 were appraised at his death at $1,270,784.

ONCE graduated, Miller began to show the energy which led him to the top of his profession. Aged 27, he married his Plainfield (New Hampshire) croquet girl, Frances Daniels, who made him an understanding and competent wife and bore him a son and a daughter.

When on the staff of the Springfield Republican he heard of an opening on the telegraph desk of The New York Times. Instead of writing a letter, he took the night train to New York and talked himself into the job. He was so quick to catch on that when the head of the telegraph desk went on vacation, the newcomer handled all telegraph copy and did not consider himself overworked. After only four years of experience in Springfield and seven on The Times, he was made Editorin-Chief at the early age of 34.

As Editor, Miller had "his office on the tenth floor of the southeast corner of the Times Annex. His window looked out over the vortex of humanity below, that orderly chaos which is city life. The chaos rather than the order of an urban crowd in motion seemed characteristic of his desk. Pamphlets, clippings, unanswered letters, journalistic jottings, manuscripts, advertisements haphazard and endless mounds of papers covered all his desk except for two square feet of working surface. Mr. Miller enjoyed his disorder so much that he forbade his secretary to do more than tidy up the heaps; he must not remove them. Should the secretary fall ill and the foothills become mountains in danger of crumbling, Miller would order a table, and transfer to it the upper regions of the peaks. On election days when there was considerable waiting around, Miller himself with the help of an army of wastepaper baskets would act as a sort of human bulldozer.

As Editor of The New York Times, Miller associated with many of the great and the near-great. He was the friend and confidant of President Grover Cleveland. Miller's New England heritage made him admire Cleveland when the President, hearing that a bill was all right but that it was not good politics to sign it, remarked, "If the bill is all right, then it is good politics to sign it."

During the McKinley administration The Times and the White House were on the most amiable of terms, for though the paper was Democratic, its criticism was always helpful and constructive. When the bullet from a murderer's gun sent Theodore Roosevelt into the Presidential chair, he wired Miller to meet him on the train taking him to Washington. The two men talked and kept on talking at luncheon at which Miller was the new President's first guest and at which there were too few lamb chops for a second helping.

Miller leaned hard on Elihu Root's friendship and legal advice. Mr. Putnam, the publisher, proposed him for membership in the Century Club, a gathering place of interesting and important persons. Miller liked club life so much that he joined also the Metropolitan and the Piping Rock.

His editorial luncheons were a sort of club extension. In a private dining room in the Times building, Adolph S. Ochs, owner and publisher, daily invited to a lavish table ambassadors, diplomats, college presidents, motion picture actresses, athletes, chemists, explorers, and anyone in the news or important and gifted. Luncheon conversations were so fascinating that they became extended, and editorial writers waiting for Mr. Ochs and Mr. Miller fumed in impatient anticipation of nearing deadlines.

Eventually with Mr. Miller and his staff, with Mr. Ochs and his executives, Arthur Hays Sulzberger and Julius Adler, and with departmental chiefs, some 17 persons in all, the editorial conference would get under way.

The leading editorial Miller himself would undertake during what remained of the afternoon and evening. Once he began, only very important persons or emergencies would be permitted to thrust themselves on him. The subject had been determined during his reading of different newspapers early in the morning, and all day long he had mulled over it, with memory, conversation, and reflection playing their unifying roles.

At about 3:45 Miller would turn his swivel chair away from his desk, rest his chin in his left hand, and half close his eyes. In such a posture he would remain silently until 4:15 or even 4:45.

Then he called his secretary, and with-out clearing his throat, without ers and ah's, without hesitation, he would dictate in flowing and flawless prose.

His methods of thought and composition were so precise that his paragraphs ran invaribly two to the typewritten page. His thinking and his memory were so close knit that if interrupted or if a second thought prompted revision, he would not even turn to the typed manuscript but say to his secretary, "Go back to the second paragraph where I said so and so, and change it to this." In later life when he dictated some editorials without the aid of written notes over the telephone from Great Neck, he would sometimes call up again and say, "Get a proof of my editorial. Read three or four lines from the end and make this alteration." So protracted were telephone calls to and from the office that Hoyt Miller gave his father a head set providing comfort and efficiency.

Happy in the routine of daily newspaper work, he was even happier when he could break the routine and engage in his private pursuits away from the office. Even during the pressure of the war years he continued his studies. When young, he had loved Latin and Greek. He read French and spoke it with such fluency and correctness that visiting diplomats were surprised and complimentary. He read and spoke German and picked up some Spanish and Italian. At the age of 68 he began the study of Russian and worked on it several hours a day. His pedagogic technique was to put up large cards with Russian letters and words at the foot of his bed for a last glimpse before sleep and a first glimpse on awaking. He took them into the bathroom when he shaved. Such doggcdness insured success, and he came to read Russian and even speak it a little.

Another life-long speciality was international law, and the honorary degrees of Doctor of Laws conferred on him by Dartmouth and of Doctor of Letters by Columbia were more than usually appropriate and deserved.

IT was in 1915 that he became a defender not merely of the honesty of himself and of The New York Times but also the champion of freedom of expression and the healthiness of private enterprise and newspapers.

He was called to Washington to testify before a Senate committee ostensibly about some allegations that ' influences had been exerted" against the then pending Ship Purchase Bill. In reality, the sessions consisted of a lengthy airing of a succession of sinister innuendoes against TheTimes, its editors and owners, and its practices. The most damning of the rumors which whetted senatorial appetite was that Mr. Ochs had sold out to the British and that British money dictated the policy of The Times and that Miller was getting his cut also.

Put in milder but nonetheless shocking terms, the senatorial inquisition came about because the editors of The NewYork Times had expressed their opinions on some questions of public policy which had not jibed with those of the Senators on the committee. So the editors were called to Washington, and the Senators asked if anybody was paying for their opinions. If so, who.

As chief spokesman not merely for TheTimes but also for all American newspapers, Miller rose perhaps to his greatest stature. Politely but icily he gave all the information requested by the Senators about how much stock in the paper Mr. Ochs owned (62 percent), how much he himself had (about 14 percent), and how much others (they were all American citiZens). He explained on request why TheTimes favored this and opposed that.

The Senators learned what they set out to learn. The Times was American and independent. No British money and no British influence played any role. German propaganda was following the successful Russian technique of today: insinuate, divide, and conquer.

At the end of the investigation Mr. Miller spoke with eloquent integrity made possible by the training in a liberal arts college, in the offices of a great newspaper, and in the heritage of New England nonconformity.

He made clear that The Times represented the American press at large. "This is not a personal issue," he pointed out. "It is a question of the extent to which a government's machinery may be privately misused to annoy and attempt to discredit a newspaper whose editorial attitude has become distasteful and embarrassing."

Finally, in defense of the American press which for some 200 years had been free of government control, Miller addressed these remarks to the committee:

"I can see no ethical, moral, or legal right," he said, "that you have to put many of the questions you put to me today. Inquisitorial proceedings of this kind would have a very marked tendency, if continued and adopted as a policy, to reduce the press of the United States to the level of the press in some of the Central European empires, the press that has been known as the reptile press, that crawls on its belly every day to the Foreign Office or to the Government officials and Ministers to know what it may say or shall say - to receive its orders."

He made clear that newspaper managers and editorial writers are persons responsible for the expression of opinion. They are men wearing neither halos nor horns. They form their opinions just as other men form theirs, by observation, reflection, and information. Nobody on TheTimes, its Editor-in-Chief insisted, was ever asked to write what he did not believe.

Miller died July 19, 1922, at the age of 73. On the following day, The Times devoted its entire editorial page, eight columns of print, each column bordered in heavy mourning black, to a eulogy and an account of his career. Centered on the page, two columns in width, was a picture of the Editor-in-Chief whose name most readers of The New York Times had seldom read in print because in accordance with its policy he wrote anonymously.

The American and English newspaper world knew better the man and his importance. In addition to the eight columns on the editorial page, The New YorkTimes saw fit to print another three and a quarter columns of editorial comment from the United States and Great Britain praising Charles Ransom Miller and his culture, his graciousness, and his spirited love of freedom and of truth.

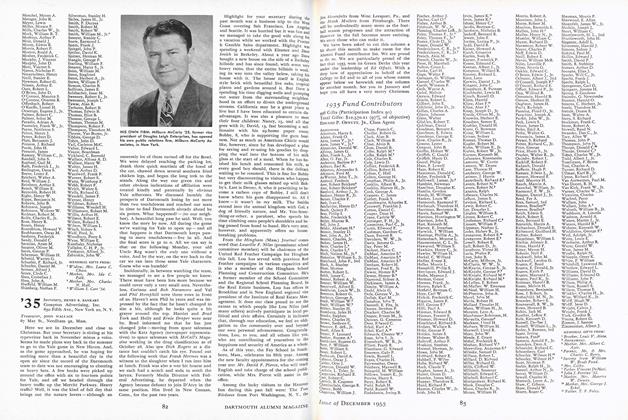

CHARLES RANSOM MILLER '72 was Editor of "The New York Times" for nearly 40 years, 1883-1922.

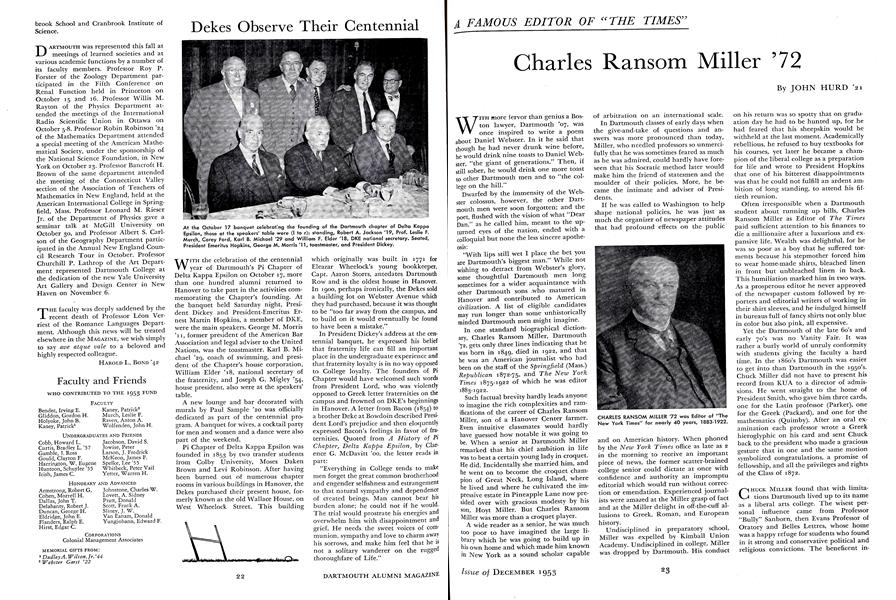

A STORMY STUDENT, Miller (third man from the left in the second row) was thoroughly sedate in this picture showing him with some of his dormitory mates on the steps of Wentworth Hall.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleBIGNESS

December 1953 By DAVID E. LILIENTHAL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

December 1953 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, w. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

December 1953 By HENRY R. BANKART, JOHN WALLACE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

December 1953 By Lambert & Feasley, Inc., PETER B. EVANS, CHARLES S. MCALLISTER -

Article

ArticleA True Dog Story

December 1953 By A. I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

December 1953 By SIMOND J. MORAND III, LT. SCOTT C. OLIN

JOHN HURD '21

-

Article

ArticleEnglish Climbing Boys

November 1949 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksENGINEERING: ITS ROLE AND FUNCTION IN HUMAN SOCIETY.

JUNE 1968 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksSELECTED WRITINGS OF OSCAR WILDE.

JUNE 1969 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksBLUFF YOUR WAY IN THE CINEMA.

OCTOBER 1969 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksALL THE BEST IN THE CARIBBEAN, INCLUDING PUERTO RICO AND THE VIRGIN ISLANDS.

NOVEMBER 1969 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksJOHN BUTLER YEATS.

January 1975 By JOHN HURD '21

Article

-

Article

ArticleGrandstand Destroyed by Fire

February, 1911 -

Article

ArticleCollege to Publish New Song Book

November 1949 -

Article

ArticleNews Service Head

April 1953 -

Article

ArticleWork Started on Orozco Book

MAY 1966 -

Article

ArticleTrack

June 1957 By Cliff Jordan '45 -

Article

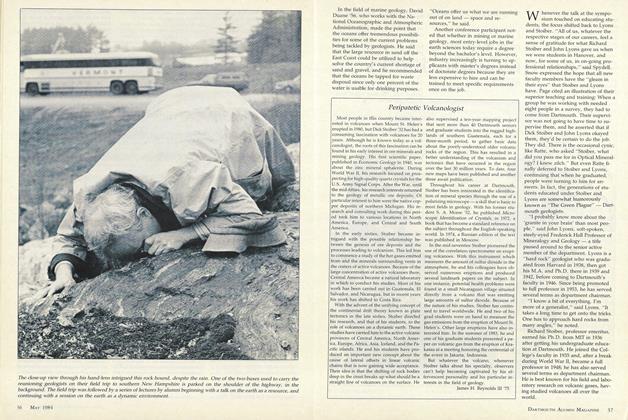

ArticlePeripatetic Volcanologist

MAY 1984 By James H. Reynolds III '75