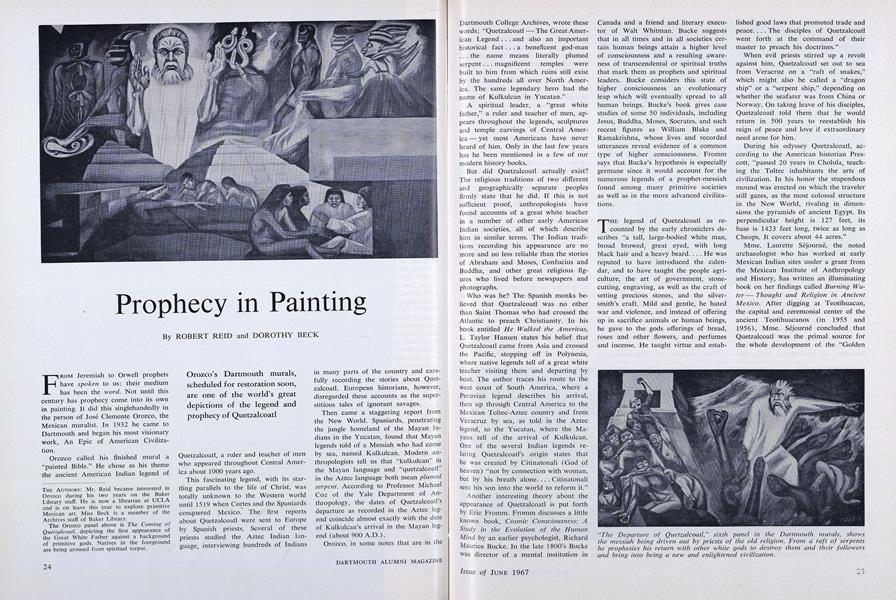

Orozco's Dartmouth murals, scheduled for restoration soon, are one of the world's great depictions of the legend and prophecy of Quetzalcoatl

FROM Jeremiah to Orwell prophets have spoken to us: their medium has been the word. Not until this century has prophecy come into its own in painting. It did this singlehandedly in the person of José Clemente Orozco, the Mexican muralist. In 1932 he came to Dartmouth and began his most visionary work, An Epic of American Civilization.

Orozco called his finished mural a "painted Bible." He chose as his theme the ancient American Indian legend of

THE AUTHORS: Mr. Reid became interested in Orozco during his two years on the Baker Library staff. He is now a librarian at UCLA and is on leave this year to explore primitive Mexican art. Miss Beck is a member of the Archives staff of Baker Library.

The Orozco panel above is The Coming ofQuetzalcoatl, depicting the first appearance of the Great White Father against a background of primitive gods. Natives in the foreground are being aroused from spiritual torpor. Quetzalcoatl, a ruler and teacher of men who appeared throughout Central America about 1000 years ago.

This fascinating legend, with its startling parallels to the life of Christ, was totally unknown to the Western world until 1519 when Cortes and the Spaniards conquered Mexico. The first reports about Quetzalcoatl were sent to Europe by Spanish priests. Several of these priests studied the Aztec Indian language, interviewing hundreds of Indians in many parts of the country and carefully recording the stories about Quetzalcoatl. European historians, however, disregarded these accounts as the superstitious tales of ignorant savages.

Then came a staggering report from the New World. Spaniards, penetrating the jungle homeland of the Mayan Indians in the Yucatan, found that Mayan legends told of a Messiah who had come by sea, named Kulkulcan. Modern anthropologists tell us that "kulkulcan" in the Mayan language and "quetzalcoatl" in the Aztec language both mean plumedserpent. According to Professor Michael Cos of the Yale Department of Anthropology, the dates of Quetzalcoatl's departure as recorded in the Aztec legend coincide almost exactly with the date of Kulkulcan's arrival in the Mayan legend (about 900 A.D.).

Orozco, in some notes that are in the Dartmouth College Archives, wrote these words: "Quetzalcoatl - The Great American Legend... and also an important historical fact... a beneficent god-man ... the name means literally plumed serpent... magnificent temples were built to him from which rains still exist by the hundreds all over North America. The same legendary hero had the name of Kulkulcan in Yucatan."

A spiritual leader, a "great white father," a ruler and teacher of men, appears throughout the legends, sculptures and temple carvings of Central America yet most Americans have never heard of him. Only in the last few years has he been mentioned in a few of our modern history books.

But did Quetzalcoatl actually exist? The religious traditions of two different and geographically separate peoples firmly state that he did. If this is not sufficient proof, anthropologists have found accounts of a great white teacher in a number of other early American Indian societies, all of which describe him in similar terms. The Indian traditions recording his appearance are no more and no less reliable than the stories of Abraham and Moses, Confucius and Buddha, and other great religious figures who lived before newspapers and photographs.

Who was he? The Spanish monks believed that Quetzalcoatl was no other than Saint Thomas who had crossed the Atlantic to preach Christianity. In his book entitled He Walked the Americas, L. Taylor Hansen states his belief that Quetzalcoatl came from Asia and crossed the Pacific, stopping off in Polynesia, where native legends tell of a great white teacher visiting them and departing by boat. The author traces his route to the west coast of South America, where a Peruvian legend describes his arrival, then up through Central America to the Mexican Toltec-Aztec country and from Veracruz by sea, as told in the Aztec legend, to the Yucatan, where the Mayans tell of the arrival of Kulkulcan. One of the several Indian legends relating Quetzalcoatl's origin states that he was created by Citinatonali (God of heaven) "not by connection with woman, but by his breath alone.... Citinatonali sent his son into the world to reform it."

Another interesting theory about the appearance of Quetzalcoatl is put forth by Eric Fromm. Fromm discusses a little known book, Cosmic Consciousness: AStudy in the Evolution of the HumanMind by an earlier psychologist, Richard Maurice Bucke. In the late 1800's Bucke was director of a mental institution in Canada and a friend and literary executor of Walt Whitman. Bucke suggests that in all times and in all societies certain human beings attain a higher level of consciousness and a resulting awareness of transcendental or spiritual truths that mark them as prophets and spiritual leaders. Bucke considers this state of higher consciousness an evolutionary leap which will eventually spread to all human beings. Bucke's book gives case studies of some 50 individuals, including Jesus, Buddha, Moses, Socrates, and such recent figures as William Blake and Ramakrishna, whose lives and recorded utterances reveal evidence of a common type of higher consciousness. Fromm says that Bucke's hypothesis is especially germane since it would account for the numerous legends of a prophet-messiah found among many primitive societies as well as in the more advanced civilizations.

THE legend of Quetzalcoatl as recounted by the early chroniclers describes "a tall, large-bodied white man, broad browed, great eyed, with long black hair and a heavy beard.... He was reputed to have introduced the calendar, and to have taught the people agriculture, the art of government, stonecutting, engraving, as well as the craft of setting precious stones, and the silversmith's craft. Mild and gentle, he hated war and violence, and instead of offering up in sacrifice animals or human beings, he gave to the gods offerings of bread, roses and other flowers, and perfumes and incense. He taught virtue and established good laws that promoted trade and peace.... The disciples of Quetzalcoatl went forth at the command of their master to preach his doctrines."

When evil priests stirred up a revolt against him, Quetzalcoatl set out to sea from Veracruz on a "raft of snakes," which might also be called a "dragon ship" or a "serpent ship," depending on whether the seafarer was from China or Norway. On taking leave of his disciples, Quetzalcoatl told them that he would return in 500 years to reestablish his reign of peace and love if extraordinary need arose for him.

During his odyssey Quetzalcoatl, according to the American historian Prescott, "passed 20 years in Cholula, teaching the Toltec inhabitants the arts of civilization. In his honor the stupendous mound was erected on which the traveler still gazes, as the most colossal structure in the New World, rivaling in dimensions the pyramids of ancient Egypt. Its perpendicular height is 127 feet, its base is 1423 feet long, twice as long as Cheops. It covers about 44 acres."

Mme. Laurette Séjourne, the noted archaeologist who has worked at early Mexican Indian sites under a grant from the Mexican Institute of Anthropology and History, has written an illuminating book on her findings called Burning Water — Thought and Religion in AncientMexico. After digging at Teotihuacan, the capital and ceremonial center of the ancient Teotihuacanos (in 1955 and 1956), Mme. Séjourné concluded that Quetzalcoatl was the primal source for the whole development of the "Golden

At the time of these reports, four hundred years ago, the discoveries by Father Sahagún and the other priests and chroniclers were considered a threat to Christianity and to the pride of the civilized peoples of Europe. Europe had believed for too long that she had reached the highest level of civilization ever known and that her religious beliefs and traditions were unique. In countries still ruled by kings and aristocracies, countries with few universities and mass illiteracy, reports about the religious and cultural attainments of "brown-skinned savages" were quickly repudiated and buried in the cellars of royal archives and monastic libraries.

When the Spanish Conquistadores under Cortes seized control of Mexico and Montezuma's Aztec Empire, they stripped it of all the wealth they could carry to Spain. They also destroyed most of its native arts and sciences, wiped out all organized religious practices dedicated to Quetzalcoatl, and broke the spirit of its people. Thus, one of the world's more advanced civilizations was reduced for years to an impoverished, backward country until the great revolutionary hero, Jáurez, laid the groundwork for its renaissance.

The Indian traditions and oral history, since they were unwritten, were rejected as fantasies and superstitions. Many of the ceremonial sites and temples, reduced to piles of rubble, were used as burial grounds for Indians massacred by the Conquistadores. The legend of the great god-man who had inspired generations of Mexicans was cast aside as just a heathen superstition. The Europeans told the conquered Mexican people, "Your history is myth, your religion is blasphemy, your beloved Quetzalcoatl is a dream that never existed." The Quetzalcoatl church and priesthood, the Quetzalcoatl-inspired Indian heritage, the very name of Quetzalcoatl, were all wiped out. Any remaining fragments were buried.

Now in the 20th century, we can rediscover Quetzalcoatl and the accounts of him left to us by the great Catholic scholar and Franciscan priest, Father Bernardino de Sahagún. Parallel events in the religious history of the Christian world and that of early Mexico are no longer considered a threat by modern Christianity. Instead, the Mexican discoveries add an element of wonder and excitement to the possibility of religious and spiritual truth for mankind. People of all religions can derive inspiration from examining the legend of Quetzalcoatl.

This Mexican legend was buried from sight until Orozco painted it across the walls of a New England college library. "Rising up between two pyramids... appears the Great White Father... the Ruler and Teacher of Men - Quetzalcoatl. It is a figure compounded at once of the attributes of a Zeus and a Jehovah, of a Confucius and a Theseus an omnipotent Creator, a lawgiver, an ethical leader, and a culture hero... the dynamic figure of the Life-Giver, on the one hand, and on the other, the lone stooping figure surrounded only by the sombre tones of a stormy sea.... It is somehow reminiscent of another grand cycle which begins with the Word and ends with the tragedy of Calvary." So wrote Artemas Packard, the far-sighted chairman of the Dartmouth Art Department, who brought Orozco to the College at the urging of Professor Churchill Lathrop, who was then a young instructor.

OROZCO chose to express himself in mural art because he felt that, unlike the oil paintings bought for collections by wealthy patrons, murals could be seen by everyone. He was convinced that the aim of his painting was the "widening and deepening of human consciousness." And was not the "widening and deepening of human consciousness" the mission and life task of Christ and Quetzalcoatl and Buddha and all the great religious figures in the history of mankind?

But what is Orozco's prophecy? His strongest statement of our future is to be seen in "The Modern Migration of the Spirit." Here in the last panel Orozco has portrayed an overwhelming figure of Christ: He is holding an axe in his right hand. Behind Him is the cross he has chopped down. Piled in a scrapheap in the background are the weapons of modern warfare and the religious symbols that separate men into different sects.

Some people who view this panel feel that Orozco is saying that Quetzalcoatl will return to America as he prophesied, and will militantly destroy our weapons and idols and lead us on a "Modern Migration of the Spirit." Other viewers are sure that Orozco is portraying the return of Christ, which has also been prophesied. Some feel that the Christ figure is only symbolic, that it is a call to mankind to fight against the injustices painted in the preceding panels. Still others believe that the Christ figure represents each human being's need to attain a higher level of spiritual consciousness, a "Christ-consciousness," as J. D. Salinger calls it. They feel that this level of consciousness is reached only by an individual migration or spiritual quest, ending in compassionate and militant involvement in the world's problems.

A major clue to Orozco's spiritual beliefs was recorded by his friend, Mackinley Helm, in a biography of Orozco, Man of Fire. "I remember receiving a letter - in the hand of Dona Margarite, his wife - regretting his absence from a New Year's Day party at my house in Mexico City. He explained at some length that his son Alfredo, then a boy of fourteen, required the father's attention in a serious illness. And though the painter lived outside the church of his forebears... he used to tell his sons that men have mystical potentialities [for higher consciousness] which they ought to try to discover and develop."

But when it came to his painting Orozco was very reluctant to impose his own beliefs upon the viewer. While Orozco was working on the murals at Dartmouth some students asked him what his paintings meant. He looked puzzled and then replied, "They mean whatever you want them to mean." In an article in the DARTMOUTH ALUMNI MAGAZINE for November 1933, he elaborated on this idea. "The stories and other literary associations exist only in the mind of the spectators, the painting acting as the stimulus. There are as many literary associations as spectators. In every painting, as in any other work of art, there is always an idea, never a story."

Orozco has starkly portrayed the conditions of our modern world and unmasked evils parading as national virtues. He has revealed to us the legend of the American Christ, Quetzalcoatl, a legend whose significance has profound implications for modern religious thought. Every thinking person should study and ponder this legend. Looking closely at the last panel, we are struck by the angry look on Christ's face. The intensity of his stare swings us backward in time. We are compelled to turn around and cross the long hall to the panel where Quetzalcoatl, departing on a raft of snakes, looks fiercely down into a room made empty by the intensity of his expression. The look is a warning; the same warning as Christ's.

From where do we come? asks Orozco. From primitive natives to warlike civilized men. And where are we going? He does not want us to go where he sees us going. And he paints it thus, as prophets have always done in time of crisis and disintegration.

"The Departure of Quetzalcoatl," sixth panel in the Dartmouth murals, showsthe messiah being driven out by priests of the old religion. From a raft of serpentshe prophesies his return with other white gods to destroy them and their followersand bring into being a new and enlightened civilization.

"The Departure of Quetzalcoatl," sixth panel in the Dartmouth murals, showsthe messiah being driven out by priests of the old religion. From a raft of serpentshe prophesies his return with other white gods to destroy them and their followersand bring into being a new and enlightened civilization.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Wallace Affair

June 1967 By C.E.W. -

Feature

FeatureRETIRING FACULTY

June 1967 -

Feature

FeatureAN ATHLETIC SUMMING UP

June 1967 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

June 1967 By RICHARD G. JAEGER, JAMES W. WOOSTER -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

June 1967 By ART HAUPT '67 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1916

June 1967 By ROGER F. EVANS, H. BURTON LOWE

Features

-

Feature

FeatureStretching the Classroom To Washington—and Michigan

January 1956 -

Feature

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

JULY 1972 -

Feature

FeatureGreen for the Holidays

January 1996 -

Feature

FeatureThe 'real world': Ivies in the cold, cold ground

JAN.- FEB. 1982 By Cliff Jordan -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCAN WE TALK?

MAY 1989 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureAffirmative Action

April 1977 By MARY ROSS