1833-1840. By Prof. Edwin Gittleman(English). New York: Columbia University Press, 1967. 436 pp. $12.50.

In September 1838, Jones Very, popular Tutor in Greek and indifferent divinity student at Harvard, threw the faculty and students of this august institution into momentary chaos by announcing that he was the Son of God. Very also let it be known that he could discern truth better than other men and that God had taken up residence within him. Because of the presence of the Holy Spirit within him, Very was incapable, he felt, of sinning. In short, the Second Coming of Jesus Christ had taken place in Jones Very, who expected that such an event would be deemed prodigious, or at least significant, by his contemporaries. Very was quickly placed in the McLean Hospital, Charlestown, an institution for the insane, where he spent a rather comfortable month. In congenial surroundings with "an audience immune to his corrupting influence," Very thought a good deal, wrote a good deal, and harmed no one.

A year later, Essays and Poems by JonesVery, rigorously edited by Ralph Waldo Emerson so as to blunt the edge of Veryist doctrine, was published by Little and Brown. The slim book, containing some forceful sonnets and eloquent lyrics as well as impressive essays on Shakespeare and epic poetry, had a limited circulation and stirred excitement only in the small group of Very's friends. Of the Transcendentalists, with whom Very was associated, only Bronson Alcott responded to the book with real enthusiasm, although Hawthorne, Longfellow, Margaret Fuller, Richard Henry Dana Sr., and William Cullen Bryant, among other notables of the time, thought well of it. According to Professor Gittleman, Very's effective life was over by the end of 1840, when he had reached the age of twenty- seven. "The sources of energy which had once given a distinctive style to his life had failed, leaving him exhausted and but little troubled." Though he lived until 1880, Very had accomplished everything worth recalling by 1840: a prolonged anticlimax followed a life, once filled with promise, suddenly eclipsed by a "fatal conservatism."

From the bald facts of Jones Very's external life, it might seem that he experienced anticlimax before he knew climax. This is certainly not the case, and Professor Gittleman more than convinces us that Very was "a writer of considerable merit and a personality of considerable brilliance." As important as Professor Gittleman's subtle analysis of Very's life and poetry is the richly detailed picture he gives us of a lively period in American cultural history, one in which Jones Very affected the transcendental way of life startlingly. This book, as the author justly claims, "is neither a clinical study of a paranoiac, nor a reverential study of a mystic." It is rather the definitive study of a peculiarly attractive poet, less marginal than Professor Gittleman too modestly insists, whose painful exercises in self- repression and consequent megalomania are archetypically, perhaps dangerously, American.

Mr. Potoker is Assistant Professor of English and Comparative Literature at The CityCollege of New York.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Fulbright Professor in France

November 1967 By FRANCIS E. MERRILL '26, -

Feature

FeatureMt. McKinley Conquered

November 1967 By Anthony H. Horan '61 -

Feature

FeatureFINAL REPORT 1966-1967

November 1967 By RALPH LAZARUS '35 -

Feature

FeatureTHE BETRAYAL OF IDEALISM

November 1967 -

Feature

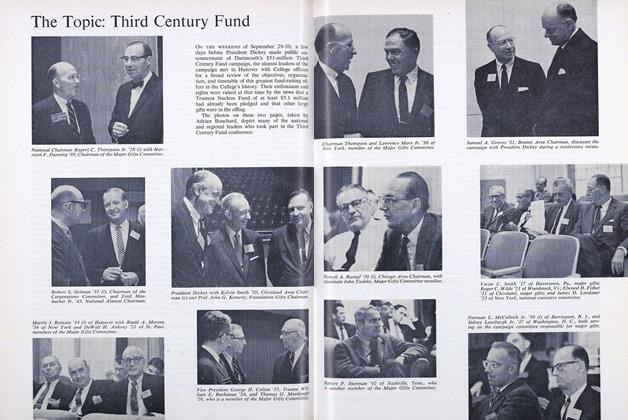

FeatureThe Topic: Third Century Fund

November 1967 -

Article

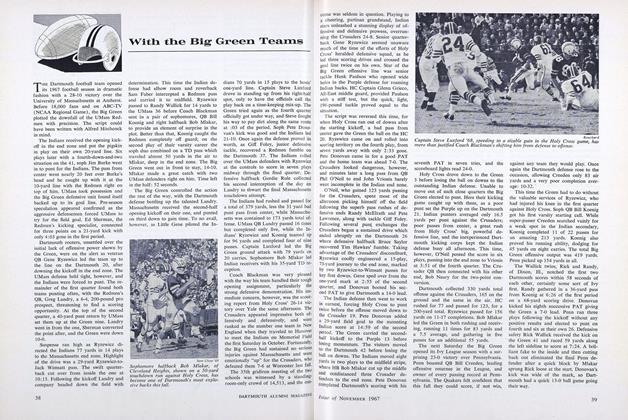

ArticleWith tine Big Green Teams

November 1967

EDWARD M. POTOKER '53

Books

-

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

July 1920 -

Books

BooksNINE SATURDAYS MAKE A YEAR.

OCTOBER 1962 By Cliff Jordan ’45 -

Books

BooksPRIVATE WOMAN, PUBLIC STAGE: LITERARY DOMESTICITY IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY AMERICA

OCTOBER 1984 By HENRY TERRIE -

Books

BooksDICTATORSHIP OF THE PROLETARIAT IN THE UNITED STATES,

November 1943 By Herman Feldman. -

Books

BooksLABOR'S SEARCH FOR MORE

May 1937 By Hugh L. Elbree -

Books

BooksA Giant Step Back

November 1979 By Richard. M. Watt '52