ByBerthold Eric Schwarz '46. New York:University Books, 1968. 243 pp. $5.95.

In 1962 Jacques Romano died at the age of 98. Romano thought he would be a centenarian. Disappointed friends and admirers were sure he was going to reach 150. This patchy biography, written by Berthold Eric Schwarz, M.D., a psychiatrist, baldly appeals to readers who might wish to keep eternity at bay. Most of us don't want to die and would willingly go almost anywhere to find the fountain of youth or be content merely to tarry in our dotage. Taking Romano's freely given advice on how to live long and die young may forestall the inevitable for some but make death still harder to bear for others.

Romano was a European immigrant who never said much about his origins. He was probably born in Spain or Italy, though no birth certificate survives. By choice his home became the U.S. and his inspiration Abraham Lincoln. In 1889 he worked briefly for Moreno and Lopez, New York photographers. He took a job with Eastman Kodak in 1900 and soon became one of their top salesmen. Travelling throughout the "Wild West," Mexico, and Latin America, he enjoyed diverse random intrigues while selling photographic equipment. An entrepreneur at heart, however, he later on manufactured a variety of iodine medicines, founding the Jamol Company in 1928. A superb practical chemist who lacked the benefits of formal education — as Dr. Schwarz too often repeats - Romano did some highly original research on the uses of iodine. His best known products were Ponaris oil, Liquidine, and Roma Nol.

But the really remarkable thing about Romano was his alchemical, rather than chemical, talent. He was psychic and clairvoyant. He could hypnotize, read minds, put people into trances. Master of sleepwalkers, Romano was an expert telepathist who worked wonders with cards. This prince of extra-sensory perception could even emit an ice-cold wind from his finger, a phenomenon known as "Romano's Ray." He never used his special gifts to exploit people, but it is no wonder that he had lively audiences.

Romano knew a lot about sex too. "Sex is a creative energy. That is why inventors and thinkers are often frigid men and why there have been so few inventors in Turkey. There, sex is used for dissipation and not procreation. Sex is exercised on (their) many wives and concubines." Another time, Romano sagely remarked, "You cannot reason with a man when he is having an erection." Which sounds like an analect from Mao Tse-tung's Cultural Revolution.

It is odd that a book written by a scientist should appear so unscientific. Much material was pieced together, the author admits, from newspaper clippings, old photographs, and haphazard memorabilia. Some of this evidence is contradictory, and some doesn't make much sense. Even odder maybe is the fact that Dr. Schwarz ignores the less sanguine dimensions of his subject. If too many of us were to benefit from Romano's example, the nation would soon have a geriatric problem almost beyond solution. Morticians would be mortified. Perhaps the Biblical injunction about living three score years and ten is more realistic than Jacques Romano believed.

Mr. Potoker is Assistant Professor of ComparativeLiterature at the Baruch Collegeof the City University of New York.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

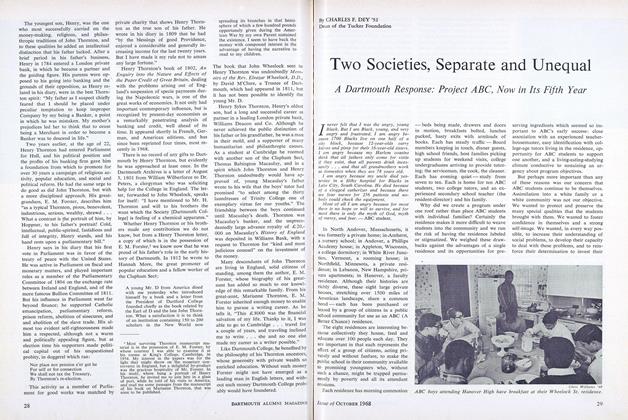

FeatureTwo Societies, Separate and Unequal

October 1968 By CHARLES F. DEY '52 -

Feature

FeatureJOHN THORNTON OF CLAPHAM

October 1968 By FRANK W. FETTER -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty

October 1968 By WILLIAM R. MEYER -

Article

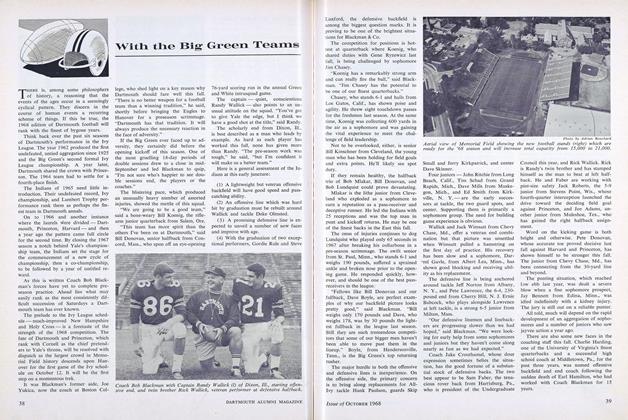

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

October 1968 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1912

October 1968 By DR. STANLEY B. WELD, FLETCHER CLARK JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

October 1968 By JOHN HURD, INGHAM C. BAKER

EDWARD M. POTOKER '53

Books

-

Books

BooksAlumni Publications

June 1935 -

Books

BooksA GUIDE TO TROLLOPE

October 1948 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Books

BooksA SYNOPTIC HISTORY OF THE GRANITE STATE,

February 1940 By Herbert W. Hill -

Books

BooksTHE CAT AND THE HAT.

June 1957 By L. G. HINES -

Books

BooksPERCEPTION AND MOTION.

MARCH 1964 By VICTOR E. McGEE -

Books

BooksTUMOR SURGERY OF THE HEAD AND NECK.

May 1958 By WILLIAM T. MOSENTHAL '38, M.D.