REFLECTIONS ON THINGS AT HAND, THE NEO-CONFUCIAN ANTHOLOGY, COMPILED BY CHU HSI & LÜ-CHTEN.

NOVEMBER 1967 T.S.K. SCOTT-CRAIGREFLECTIONS ON THINGS AT HAND, THE NEO-CONFUCIAN ANTHOLOGY, COMPILED BY CHU HSI & LÜ-CHTEN. T.S.K. SCOTT-CRAIG NOVEMBER 1967

Translated, with notes, byProf. Emeritus Wing-tsit Chan. NewYork: Columbia University Press, 1967.441 pp. $12.50.

"According to the Principle of Heaven and Earth and all things, nothing exists in isolation but everything necessarily has its opposite. All this is naturally so and is not arranged or manipulated. I often think of this at midnight and feel as happy as if I were dancing with my hands and feet." The dance would be more like a minuet than a Dionysiac congo line, for we also learn that "The Mean is the great foundation of the universe"; and the Mean, "which is stable, correct, and straight up and straight down" is like a weighing balance, which is perfectly level.

These are typical metaphysical remarks, characteristic "reflections on things at hand," which appear in the scholarly yet eminently readable translation, by our sorely missed Wing-tsit Chan, of writings which dominated Chinese education and culture for eight centuries. They are utterances of the New Confucians, who in time and content are to Confucius as Thomas Aquinas is to Augustine in the West.

In form, the book is a series of philosophical conversations stemming from four of the eleventh century A.D. founders of the New Confucianism, as edited and commented on chiefly by Chu Hsi, an even more important successor a century later. And since "things at hand" are what can be of immediate application, what is of daily concern, a great deal of the volume is taken up with "Preserving One's Mind," "Correcting Mistakes," "The Way to Regulate the Family" and not least "On Serving or Not Serving in the Government." One of the last sections, "Sifting Heterodoxical Doctrines," shows, to put it mildly, a certain lack of admiration for the Way of Lao Tzu and for the Teachings of the Compassionate Buddha.

The general editor, of the series in which this volume appears, rightly claims that this is a work which any educated man should have read; till now he did not have the chance, but now he really has. I would go further; I think it is indispensable background reading for any educated man who wants to know (as he needs to know) what the various modernizations of China are really all about whether it be the activities of Christian missionaries, of the Chiang Kai-sheks, of Mao Tse-tung, or even of those terrifying Red Guards.

In a necessarily brief review I cannot give more than an indication of the riches in this volume, but for those of Professor Chan's former students who do not happen to own his Source Book in Chinese Philosophy, I do want to mention that this work also includes, as an appendix, his invaluable essay "On Translating Certain Chinese Philosophical Terms." In it "Jen" and "Li" and "Te" become accessible to all.

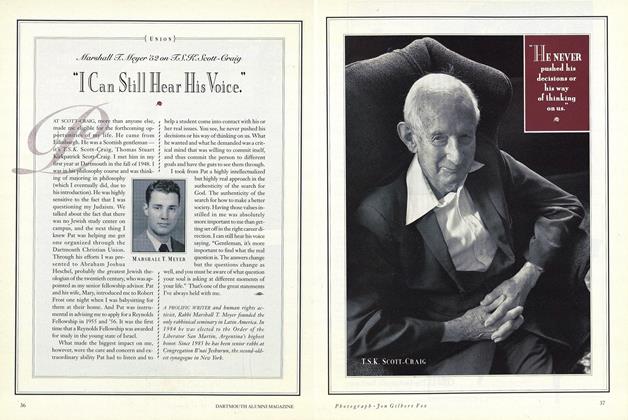

Mr. Scott-Craig, Professor of Philosophy atDartmouth, this year is teaching courses inMedieval Philosophy and. the Philosophy ofArt.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Fulbright Professor in France

November 1967 By FRANCIS E. MERRILL '26, -

Feature

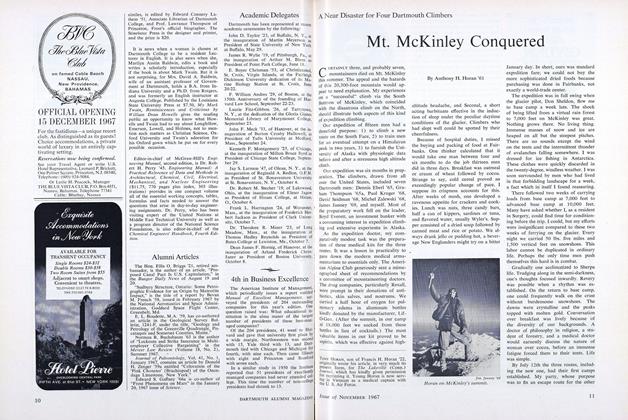

FeatureMt. McKinley Conquered

November 1967 By Anthony H. Horan '61 -

Feature

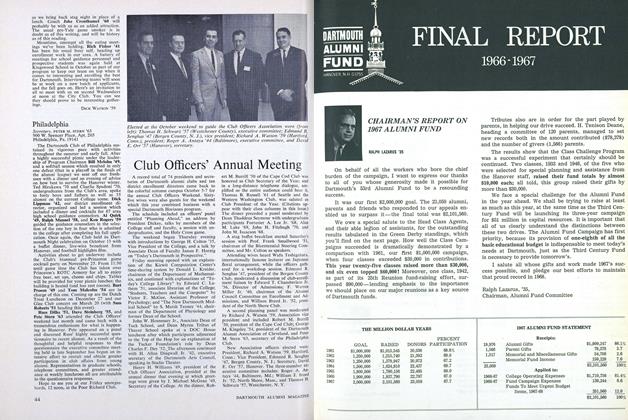

FeatureFINAL REPORT 1966-1967

November 1967 By RALPH LAZARUS '35 -

Feature

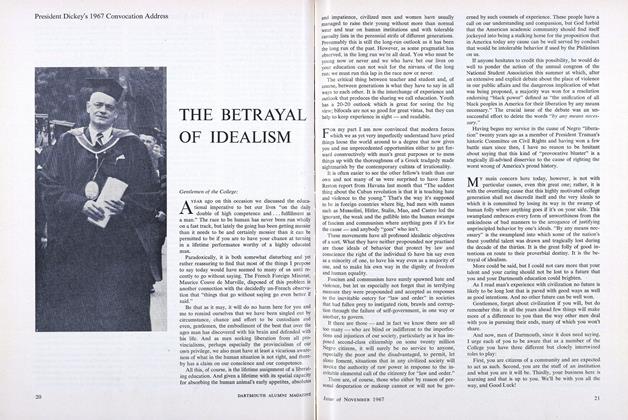

FeatureTHE BETRAYAL OF IDEALISM

November 1967 -

Feature

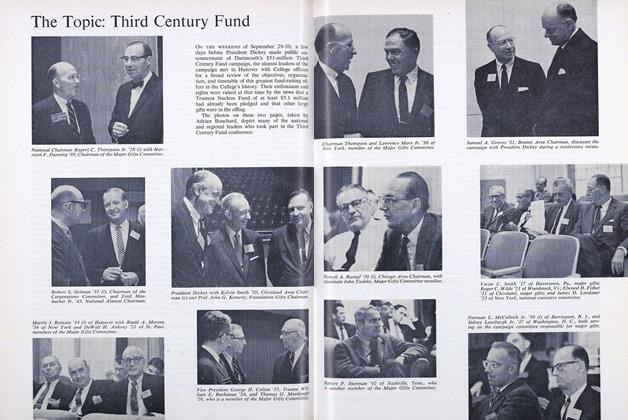

FeatureThe Topic: Third Century Fund

November 1967 -

Article

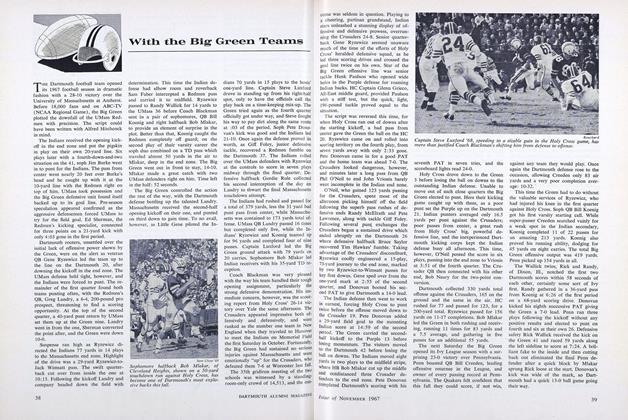

ArticleWith tine Big Green Teams

November 1967

T.S.K. SCOTT-CRAIG

-

Books

BooksCATHOLIC VIEWPOINT ON CHURCH AND STATE.

December 1960 By T.S.K. SCOTT-CRAIG -

Books

BooksTHE WAY OF LAO TZU.

JUNE 1964 By T.S.K. SCOTT-CRAIG -

Books

Books"SPEAK THAT I MAY SEE THEE!": THE RELIGIOUS SIGNIFICANCE OF LANGUAGE.

OCTOBER 1968 By T.S.K. SCOTT-CRAIG -

Feature

FeatureMarshall T. Meyer '52 on T.S.K. Scott-Craig

NOVEMBER 1991 By T.S.K. Scott-Craig

Books

-

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

February, 1922 -

Books

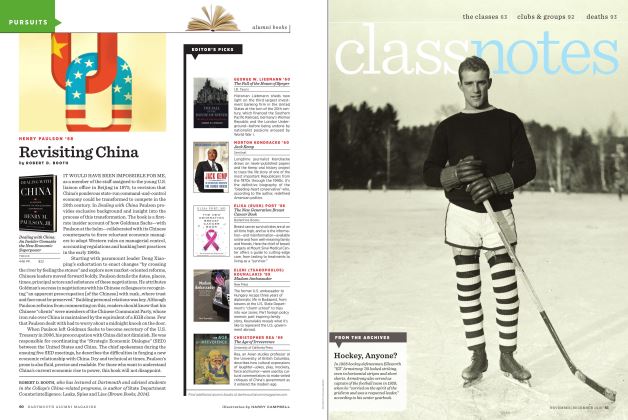

BooksEDITOR'S PICKS

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2015 -

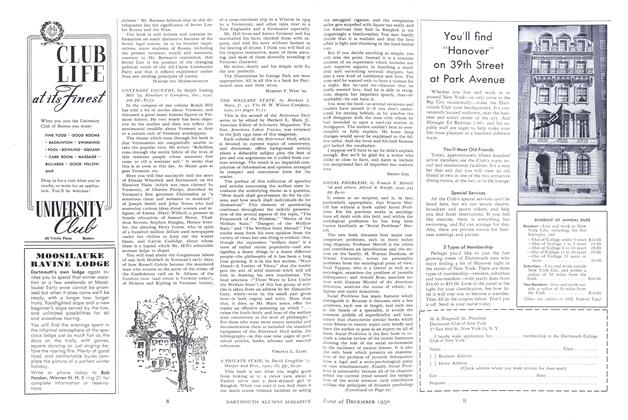

Books

BooksA TREASURY OF AMERICAN CLOCKS.

JUNE 1969 By CHARLES S. PARSONS -

Books

BooksThis Sceptered Isle

December 1978 By DAVID M. SHRIBMAN '76 -

Books

BooksNotes on travelers who tread the paths that angels fear, and the road signs they post along the way.

June 1979 By R. H. R -

Books

BooksA PRIVATE STAIR

December 1950 By SIDNEY COX