COME spring these things change up at the College Grant; it's time for the "drive." Dartmouth undergraduates and alumni who are familiar with the 27,000-acre Second College Grant tract, most likely appreciate its summertime lethargy - limpid trout pools on the Dead Diamond - or the "seclusion" one finds in the fall, especially during hunting season. As one hunter put it, in his entry in the Alder Brook Cabin logbook at the end of a week's unsuccessful hunting, "Tomorrow I'm going out and blow hell out of a tree." But the early spring activity — at the Grant spring takes up roughly the last half of April - is something few people see or, perhaps, know about.

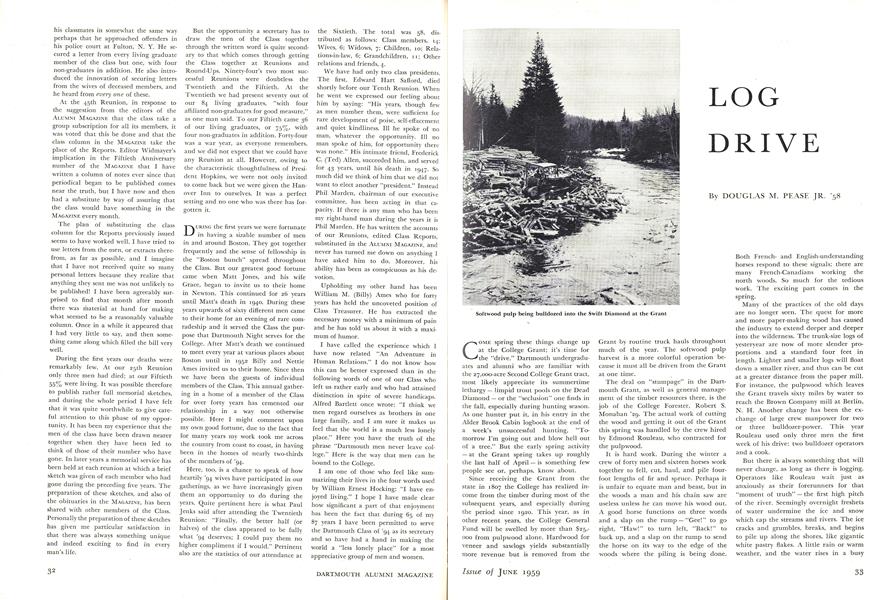

Since receiving the Grant from the state in 1807 the College has realized income from the timber during most of the subsequent years, and especially during the period since 1920. This year, as in other recent years, the College General Fund will be swelled by more than $25,000 from pulpwood alone. Hardwood for veneer and sawlogs yields substantially more revenue but is removed from the Grant by routine truck hauls throughout much of the year. The softwood pulp harvest is a more colorful operation because it must all be driven from the Grant at one time.

The deal on "stumpage" in the Dartmouth Grant, as well as general management of the timber resources there, is the job of the College Forester, Robert S. Monahan '29. The actual work of cutting the wood and getting it out of the Grant this spring was handled by the crew hired by Edmond Rouleau, who contracted for the pulpwood.

It is hard work. During the winter a crew of forty men and sixteen horses work together to fell, cut, haul, and pile four-foot lengths of fir and spruce. Perhaps it is unfair to equate man and beast, but in the woods a man and his chain saw are useless unless he can move his wood out. A good horse functions on three words and a slap on the rump — "Gee!" to go right, "Haw!" to turn left, "Back!" to back up, and a slap on the rump to send the horse on its way to the edge of the woods where the piling is being done. Both French- and English-understanding horses respond to these signals; there are many French-Canadians working the north woods. So much for the tedious work. The exciting part comes in the spring.

Many of the practices of the old days are no longer seen. The quest for more and more paper-making wood has caused the industry to extend deeper and deeper into the wilderness. The trunk-size logs of yesteryear are now of more slender proportions and a standard four feet in length. Lighter and smaller logs will float down a smaller river, and thus can be cut at a greater distance from the paper mill. For instance, the pulpwood which leaves the Grant travels sixty miles by water to reach the Brown Company mill at Berlin, N. H. Another change has been the exchange of large crew manpower for two or three bulldozer-power. This year Rouleau used only three men the first week of his drive: two bulldozer operators and a cook.

But there is always something that will never change, as long as there is logging. Operators like Rouleau wait just as anxiously as their forerunners for that "moment of truth" - the first high pitch of the river. Seemingly overnight freshets of water undermine the ice and snow which cap the streams and rivers. The ice cracks and grumbles, breaks, and begins to pile up along the shores, like gigantic white pastry flakes. A little rain or warm weather, and the water rises in a busy rush to clear its channels of all obstructions. Ice, silt, pebbles . . . and logs are swept to the end of its course.

Every year it's a gamble. If the river does not rise high enough for a long enough time, the operator has to truck out his wood at a tremendous cost and over roads axle-deep in mud. Just one of the bulldozers alone reduced a road to ruts about two and a half feet deep - and all mud. Either this, or the river might go down as quickly as it rose, leaving a logclogged shoreline with no payload at the end.

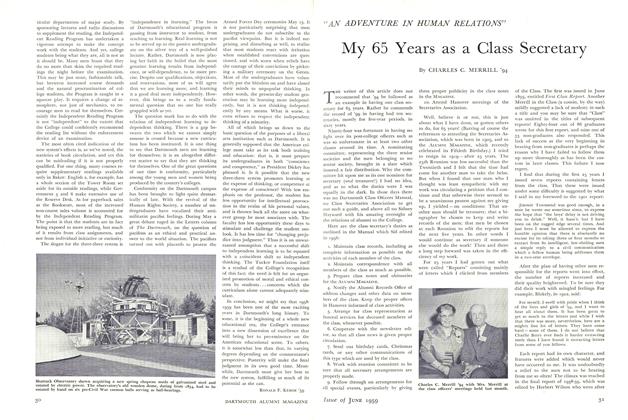

This year, however, things went well. The river rose high enough to start the drive at dawn, the 17th of April. For the first part of the operation, the two bulldozers started in on a ten-day battle with five thousand cords of wood. One cord of wood is four feet by four by eight; five thousand of them is about four miles on the shores of the Swift Diamond River, stacked three and four rows deep.

The 'dozers would start at the end of a pile, tumble down the neatly stacked logs, and sweep them into the river, or else simply shove them over the embankment. Everything was made much more difficult by the fact that snow and ice had frozen the logs together the way mortar binds bricks. It was about the same chore as chipping cubes out of an ice tray.

The second and by far the most interesting phase.of the drive, known as "rearing," began as the bulldozers neared the end of their job. Here's where individual skill, stamina, and knowledge of the woods come into play. Old Joe Fortin has been in the woods for 53 years, and he has been "driving" for forty. In this man are combined all the skills and "know-how" of the good "rearer."

Rearing consists of walking down the shores of the river and pushing stray and grounded logs back into the mainstream. Or there might be smaller piles of wood that the 'dozers could not reach, or there may be a lot of wood that the 'dozers did not clean up; it all has to go into the river.

The "rearer" is equipped with a pickpole, for moving logs already afloat; a picaroon, for latching onto stacked or stranded logs; and an axe, for cutting stacked logs free of the ice which binds them, as well as cutting away, occasionally, some of the innumerable snags and branches which trap logs at the river's edge.

Armed with these three tools, the "rearer" must either sink or swim . . . sometimes literally so. Each log is treated like the Biblical hundredth sheep, and stray logs get hung up, generally, in the most precarious places. Pull too hard on a picaroon — a beak-like pick at the end of an axe-handle — and it comes out of the log. If you have pulled with your legs and back as well as your arms, you lose your balance and . . . splash! Miss a stab with a fifteen-foot pick-pole, and if you've stepped into the thrust, you just keep going . . . splash! Or just lean the wrong way at the wrong split-second in the light aluminum boat used to clean the snags in the middle of the river — the boat broaches in the white-water torrent and . . . splash! All of these your reporter has done, or seen done. It's easy, if you don't know how.

And yet Old Joe does not make these mistakes. He poles out logs from the boat, standing in the bow like a bobbing cork monkey. He moves three logs in a jam, and all the rest somehow move out into open water. Moving through woods or water, pitching, picking, or poling, Joe makes every move count, and quickly. He figures "it's a long time before night, mister, so don't wear yerself down by wastin' yer energy. Do it right and make it count. . . ." And 67-year-old Joe Fortin can still fill in the 10-hour day better than most men.

It took about fifteen men to "rear" the nine miles of the Swift Diamond River, from the first wood pile down to the Magalloway. Two weeks' work, and at last all the wood lay in the quiet waters, ready to join the main Brown Company drive down the Magalloway, across the outlet of Umbagog Lake, and on down the Androscoggin to the paper mills at Berlin.

The "drive" is over for this year, but the men are already building a new camp, fixing up chain saws and axes, and laying in supplies for another round of cutting for next spring's drive.

Softwood pulp being bulldozed into the Swift Diamond at the Grant

5,000 cords of wood were stacked like this along the river for four miles

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureMy 65 Years as a Class Secretary

June 1959 By CHARLES C. MERRILL '94 -

Feature

FeatureA Panathenaic Prize Amphora

June 1959 By DIETRICH VON BOTHMER -

Feature

FeatureRetirement Nears for Seven Dartmouth Professors

June 1959 -

Article

ArticleThe Fraternity Discrimination Issue

June 1959 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

June 1959 By RONALD F. KEHOE '59 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1936

June 1959 By JOHN A. SAWYER, C. KIRK LIGGETT

Features

-

Feature

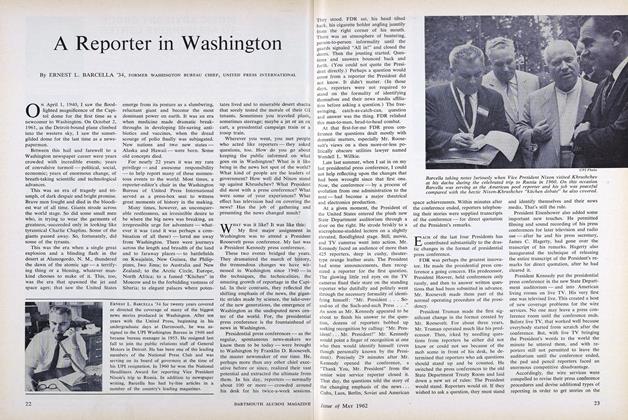

FeatureA Reporter in Washington

May 1962 By ERNEST L. BARCELLA '34 -

Feature

FeatureOn a Freshman Trip, the Destination Is Community

MARCH 1989 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

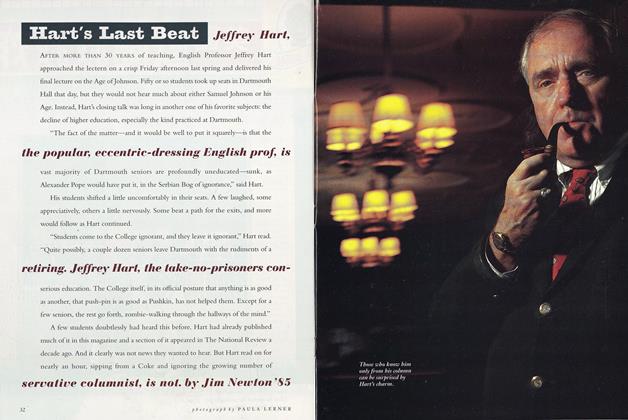

FeatureHart’s Last Beat

NOVEMBER 1992 By Jim Newton ’85 -

Feature

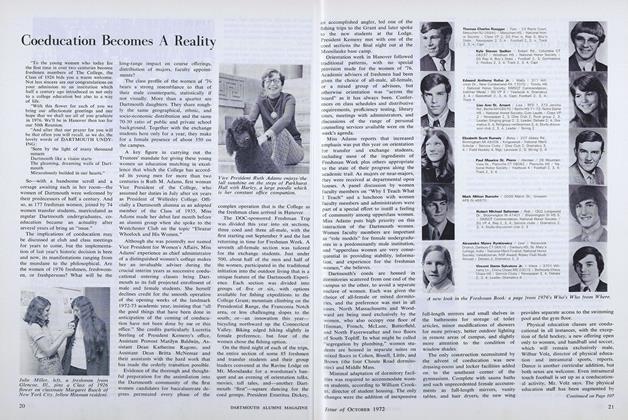

FeatureCoeducation Becomes A Reality

OCTOBER 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

FeatureNomss de Blitz

OCTOBER 1998 By NOEL PERRIN -

Feature

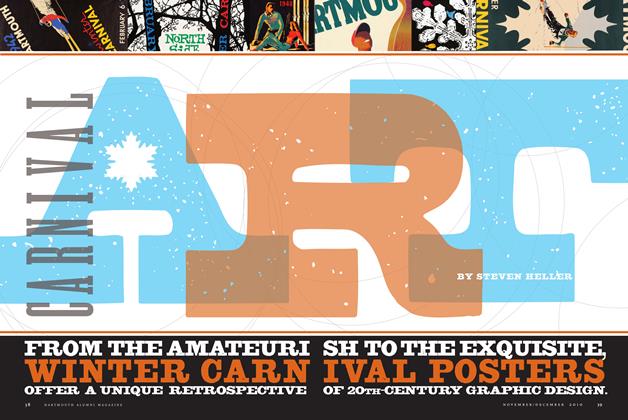

FeatureCarnival Art

Nov/Dec 2010 By STEVEN HELLER