Objectivity v. selectivity and diversity

IT is important to stipulate what I am not attempting to do. I do not have the competence to discuss the legal issues involved in the Bakke Case. Nor do I wish to comment on the specific admission policy of the medical school at Davis, which is quite different from that of Dartmouth College. Nor is it my purpose to discuss "affirmative action," which deals with policies concerning employment practices rather than the admission of students. What I do wish to do is discuss an issue of major importance to all of higher education in general, and to Dartmouth College in particular. While the immediate reason for writing this has been the Bakke Case, the remarks I am about to make do not differ from remarks I would have made in the absence of this particular case.

IT is my fundamental belief that it is in the best national interest to allow considerable diversity among institutions of higher education. No institution, no matter how large or how well financed, can be all things to all people. Therefore, diversity allows applicants a considerable degree of choice among institutions they wish to attend, and allows different institutions to fulfill widely differing purposes. For example, M.I.T. is one of the great educational institutions in the world. But its purpose is different from that of Dartmouth College and, therefore, it will use different criteria in the admission of students. It is not a question of one institution being better than the other, but of being different. I believe that any thoughtful observer would agree that it would be just as wrong to force Dartmouth College to imitate M.I.T., as to force M.I.T. to become like Dartmouth College. The point seems obvious; but it is equally important that in structuring both the undergraduate programs of various institutions and the mix of the student body, each institution should be allowed to implement its unique institutional purpose.

My major concern is that a ruling by the Supreme Court in the Bakke Case might, inadvertently, force institutions to change their fundamental purposes. And any attempt by the courts to lay down uniform rules for admission would have the effect of reducing the degree of diversity among institutions, which would be highly undesirable.

CHARGES of reverse discrimination are usually based on the fact that one candidate has higher scores on so-called objective tests than another candidate. The first observation I must make is that Dartmouth College has never admitted students purely on objective scores. Indeed, no single criterion determines the admission of a student.

Any institution fortunate enough to have many more applicants than places in the freshman class must make choices. The Admissions Office, under policy guidelines laid down by the Board of Trustees, shapes the composition of each freshman class to fit our institutional purpose. The Board has recently re-stated Dartmouth's purpose as "the education of men and women with a high potential for making a significant positive impact on society." Our purpose is not "the education of students who have the ability to accumulate high gradepoint averages at the College."

Objective scores, such as those on College Board tests, are useful in the admissions process. Since the tests are national, performance on them may be more meaningful than grades accumulated in high schools, which have widely varying standards of grading. These test scores are helpful to the Admissions Office in identifying students who could probably not do the work at Dartmouth, or who could do the work only at so high a price that they could not take full advantage of the varied opportunities offered by the College. But even this determination is not based on one or two numbers, but on the overall record presented by the applicant.

Since the inception of the Selective Process of admission, in 1921, the College has placed as much emphasis on personal qualifications of an applicant as on his or her academic qualifications. The Admissions Office has the right to turn down an applicant with the very highest academic qualifications if, in their judgment, he is lacking in human qualities. And it is quite common to admit a student with significantly lower College Board scores but outstanding personal qualifications in preference to someone with higher scores. This has been our policy for several decades, and it is a policy that was arrived at irrespective of the question of race.

But the question of race does enter into the interpretation of the so-called objective test scores. I can testify to the problems involved in such interpretation from personal experience. When I took the College Boards, I scored rather spectacularly on the mathematical aptitude test, but I had a very poor score on the verbal test. This was hardly surprising in view of the fact that at that time I had been in the United States for only two and a half years. I'm certain that my admissions dossier must have had a "foreign student" label on it, since I was admitted to an Ivy League institution in spite of my verbal score. The point is that, while the Educational Testing Service tries very hard to measure aptitude, they cannot measure it in a vacuum. The verbal aptitude test must use English vocabulary, and it has tended to use a rather sophisticated vocabulary. This is eminently unfair to someone whose native language is not English. The traditional way of handling this is not to abolish the verbal aptitude test, but to modify its interpretation in those cases where the test is less than fair.

Similar considerations apply to students from a disadvantaged background, many of whom tend to be minority students. If you grow up in a very poor neighborhood and your parents did not have the advantages of any significant amount of education, you are unlikely to have acquired a sophisticated vocabulary. Interpreting the verbal aptitude score for such a student as actually demonstrating lack of verbal aptitude would be discriminatory. We and our sister institutions have proved repeatedly that such students, given the advantages of a fine education, can eventually perform at the level of those students who entered with the highest scores. Unfortunately, they are often called "risk students," a phrase that lends itself to the interpretation that the institution has admitted students of lesser ability. Instead, what has occurred is that we have students for whom our normal criteria of admission are not reliable guides to their aptitudes.

ONE of the great strengths of a residential college is the fact that education inside the classroom is supplemented with valuable experiences outside of class. For this strength to achieve its full significance, it is essential that the institution should attract' a highly varied student body. For example, Dartmouth prides itself on being a national institution. While we do acknowledge a special indebtedness to northern New England, we attract students from every state of the Union and from many foreign countries. The fact that a student from New York City may find that his freshman roommate is from New Mexico provides the potential for significant enrichment of his experience at Dartmouth.

Part of the charge to the Admissions Office is to produce as varied a student body as possible, consistent with the students' ability to take full advantage of a Dartmouth education and consistent with the fundamental purpose of the institution. In this process, geographic diversity is but one of many considerations. We have given, and do give, substantial preference to the children of alumni. I have always been a strong advocate of this preferential admission of "legacies." Having a significant fraction of each entering class consist of students who already are familiar with the values and traditions of the College is important for providing continuity for these traditions. In addition, an institution that relies as heavily on the support of its alumni as does Dartmouth - support both financial and in terms of a wide variety of services - must recognize this indebtedness in its admission policy. The College also has given preferential admission to students with a variety of different talents. We are always looking for evidence of leadership potential. We may admit a brilliant musician even if his or her scores are lower than average. And we have given, and do give, preference to outstanding athletes. It would be tragic if the Court interfered with our ability to make such choices, by requiring institutions to base admission purely on objective scores.

An important step in the further diversification of Dartmouth's student body occurred in 1968 when the Board of Trustees approved the Equal Opportunity Program. To attract a much larger number of minority students to the College, it was recognized that significant recruitment would have to take place, and special support services might have to be available on campus to correct past educational deficiencies. The Board had two reasons for adopting this policy: Dartmouth's historic role of training leaders for the nation among non-whites as well as whites and the benefit of a significant number of minority students in helping to sensitize the entire student body to the special problems faced by minorities.

Our largest and most successful minority program has been for black students. But considering the history of the College, equally important is our attempt to attract each year a number of highly promising American Indian students. After all, Dartmouth's 1769 charter authorized establishment of a college in the Province of New Hampshire "... for the education and instruction of Youth of the Indian Tribes in this Land in reading, writing and all parts of learning . . . and also of English Youth and any others."

It is not surprising that many American Indians on entering a school like Dartmouth College experience significant culture shock. One of our most challenging tasks is to attract students who are able to take advantage of a Dartmouth education and who have the determination to improve the lot of American Indians. The need is so great that even graduation of a relatively modest number of potential leaders among Native Americans would be a significant contribution by the College. It would be the ultimate irony if a court ruling intended to bar discrimination should prevent Dartmouth College from carrying out the purpose of its 200-year-old charter.

I find the concept of a fixed quota for a given racial group abhorrent. I know that there are many people whom I respect who will argue that such quotas are necessary to achieve a higher purpose. But my childhood was spent in a country where quotas were prevalent, and their sole purpose was to discriminate against Jews. I'm proud of the fact that Dartmouth College does not have any religious quotas, indeed that an applicant's religion is not considered during the admission process. It is equally important to understand that we do not have quotas for minority students.

Perhaps the recent history of the admission of black students to Dartmouth will help to illustrate this point. We do have a strong and well-organized effort to attract black students to the College and to make the College as hospitable an environment for them as possible. As other institutions launched strong equal opportunity programs, we found increasingly that we were not the first choice of many black applicants. The fact that some of our sister institutions are located much closer to cities with significant black concentrations helped them and hindered us. We therefore increased our efforts, and thanks in large part to the renewed participation in the recruitment process of many of our black alumni, we have just had our most successful year for attracting black students to the freshman class. The number of black students in the Class of 1981 will be about 30 per cent higher than that in the previous class. If we had had a fixed quota for black students, we would have been forced in the Class of 1980 to admit a number of students who were not qualified for the College. And that same quota would have barred a number of wellqualified students from entering with the Class of 1981.

While I strongly support our present Equal Opportunity program, I regret the necessity for it. In effect, we are helping various minorities to assume their rightful place in our society. It is my fervent hope that, if we do a sufficiently good job with the present generation, in another generation we may totally ignore the question of race in the admission process.

The case of Allan Bakke, who has chargedthe University of California at Davis withreverse discrimination in denying him admission to medical school while reserving16 of 100 positions for minority students,will be heard this month by the U.S.Supreme Court. As a result, college anduniversity admissions policies have comeunder extraordinarily close scrutiny.Dartmouth, with a group of similar institutions, had hoped to file an amicus curiae brief with the court, reflecting theirjoint thinking on the matter. Such a briefwas drawn up by a team of law professors,but the deadline for filing passed before allthe parties had the opportunity to agree oncommon wording.

Hence the Dartmouth Trustees urgedPresident Kemeny to issue a statement ofhis own on "the philosophy and rationaleof Dartmouth's admission policy, withspecial attention to the admission ofminority students." In drafting his statement, the President has acknowledged thebenefit of reading drafts prepared by hiscounterparts at two other institutions.In two other instances in Dartmouth'spast, presidents of the College have beenprompted by their consciences to take controversial stands on matters involvingracial or religious discrimination inironically different circumstances and,in so doing, have inadvertently become causes celebres in the public press. In 1863,

public indignation over Nathan Lord'sconviction that the institution of slaverywas divinely ordained ultimately led to hisresignation after 35 years' tenure. In 1945,Ernest Martin Hopkins, while welcomingJews as students or alumni, defended"proportionate selection" of Jewishapplicants, lest Dartmouth "become an urban college" and "lose its racialtolerance." In response to newspapercharges of anti-semitism, College officialsdeclared that "Dartmouth has never hadany so-called Jewish quota, that it hasnone now, and that it has no intention ofadopting one" without, however, explaining how "proportionate selection"operated.

In 1824, Edward Mitchell, a Negro whom President Brown had brought as a servant to Hanover upon his return from the South, applied for admission to the College. The Trustees, fearing objections from the undergraduates, refused to grant his request. Whereupon the students petitioned that he be admitted, and the Trustees willingly yielded to their request, a hospitality to the Negro race which has remained the policy of the institution to the present day. - L. B. Richardson, History of Dartmouth College

An usually high proportion of our Negro alumni, as compared with our total alumni body, have gone into the different professions.... Of the [89] Negroes who attended Dartmouth before 1936, there are twenty-nine physicians; twenty-one in educational work; four lawyers; three dentists; two ministers; an engineer; a journalist; an accountant; a librarian; a pharmacist; and a welfare worker. Of the five Negroes who have graduated since 1936, three are now studying medicine, one is studying engineering, and one is studying for his Ph.D. in American culture.... - Letter from the Secretary of the College to the President, 1940

It takes five years to learn what Dartmouth meant. When we got out, it was a good feeling to be paroled, but now we recognize a tradition of excellence like three black Rhodes Scholars in four years. - Keith Jackson '70

It's not that they're bad people, but that they're all the same. They tend to have the same backgrounds; they work on the same assumptions. - Dean Warner Traynham '57, on white males predominant at Dartmouth

I don't see why Dartmouth has to accept any scholarship students, when there are more than enough good strong candidates able to pay their own way. It would save a lot of money. - Unidentified alumnus

Dear Sir: In the tenth grade I was happy to begin my new experience at a new and unfamiliar school.... Most of the students in the classes were much more ahead of me. For example, when my English teacher asked the class for certain books we had read, all of these students had read these books but me. must say it was a strain at first, for I had not been used to doing work I hardly ever understood. . . . Also I found out you could not ask so many questions. Many of my teachers got so offended so I stopped asking so many questions and that didn't help much either. . . . After talking to many students from other high schools and my own school we decided to form an organization to talk about student needs and ways and means of making the educational institution a better experience.... I spent many nights going to meetings and knowing I had much homework to do.... I won't explain our involvement but if you know anything of Oakland education you know we are graduating students who can't read and write.... There was little publicity on all the violence that occurred in this year but it did happen. A band room was burned down, a teacher was in the hospital in critical condition, Molotov cocktails were being thrown. Twelve rifles were found in some lockers. A girl was killed.... You see it was urgent that we students got together to keep violent students cool, and students that were high to stop it. The whole situation was making me nervous and I really couldn't think of anything else. At the end of the school year I was pretty torn apart from being so active and trying to talk to apathetic students and adults.... My grades were lacking what I could show.... ... If I get accepted you will not regret that I was one of the students you chose. I hope this will help you a little in understanding more about me, and also to influence your decision. - Letter of application from a black student, 1970. He was not admitted.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureMen and Women: What's the Difference?

October | November 1977 By Dan Nelson, Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureThe Singing of the Cider

October | November 1977 By Sanborn Brown -

Feature

FeatureWith Pen In Hand...

October | November 1977 By Arnold Roth -

Class Notes

Class Notes1971

October | November 1977 By THOMAS G. JACKSON -

Article

Article"My hardships were excessive"

October | November 1977 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1948

October | November 1977 By FRANCIS R. DRURY JR

John G. Kemeny

-

Feature

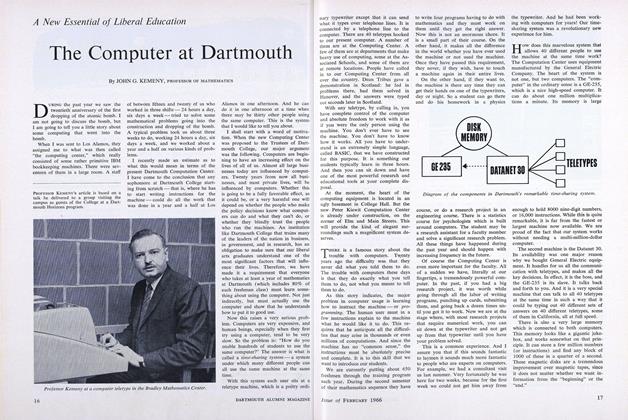

FeatureThe Computer at Dartmouth

FEBRUARY 1966 By John G. Kemeny -

Article

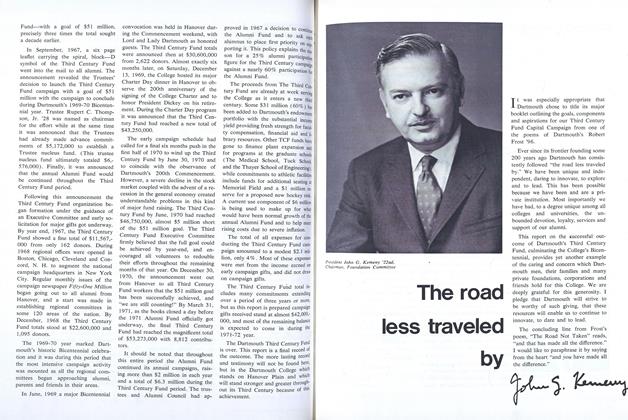

ArticleThe road less traveled

DECEMBER 1971 By John G. Kemeny -

Feature

FeatureFive Deadly Threats

November 1976 By John G. Kemeny -

Article

ArticleI was enormously moved

April 1979 By John G. Kemeny -

Feature

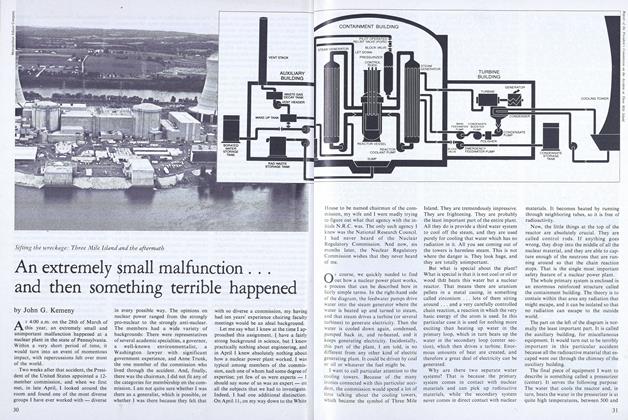

FeatureAn extremely small malfunction ... and then something terrible happened

December 1979 By John G. Kemeny -

Cover Story

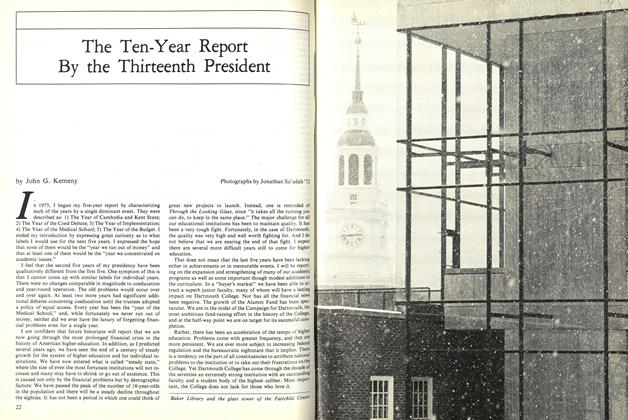

Cover StoryThe Ten-Year Report By the Thirteenth President

June 1980 By John G. Kemeny

Features

-

Feature

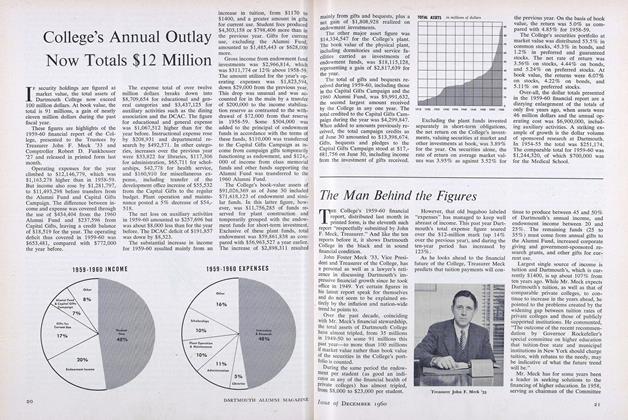

FeatureThe Man Behind the Figures

December 1960 -

Feature

FeatureThe Class Officers Weekend

JUNE 1970 -

Cover Story

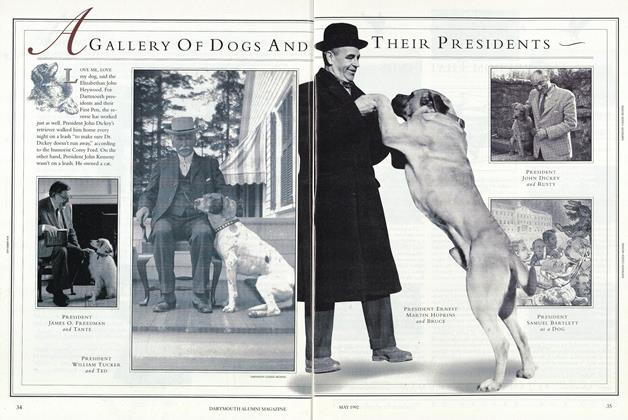

Cover StoryA Gallery Of Dogs And Their Presidents

MAY 1992 -

Feature

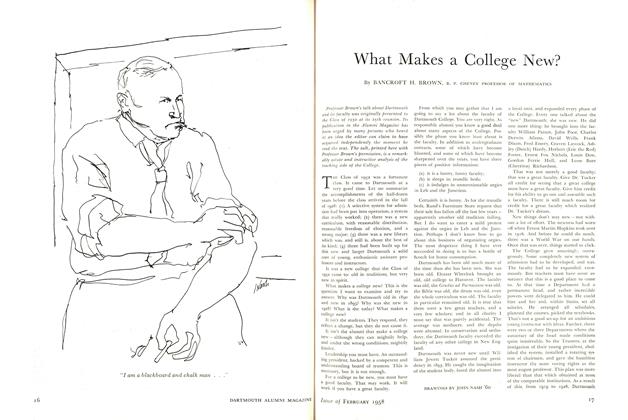

FeatureWhat Makes a College New?

February 1958 By BANCROFT H. BROWN, B. P., JOHN. NASH '60 -

Feature

Feature... AND MANY DARTMOUTH YESTERDAYS

October 1961 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Cover Story

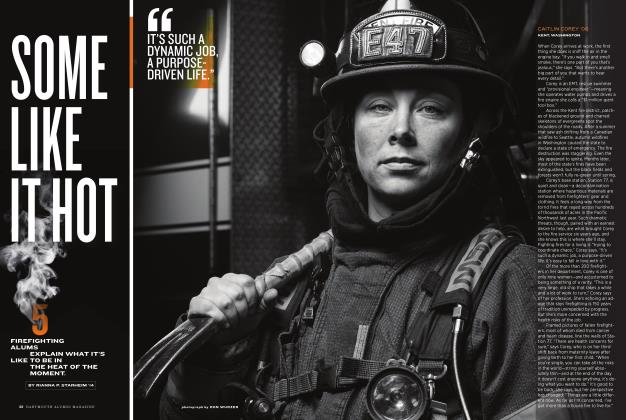

Cover StorySome Like It Hot

MARCH | APRIL 2018 By RIANNA P. STARHEIM '14