The author says NO, and goes on to claim that amateurs on the campus, as creators and critics, have something to tell the old cinema pros

WHEN you attend a Conference on Film Study in Higher Education, as I did at Dartmouth in 1965, and when you hear scholars discussing a variety of approaches to the study of film art, history, and technique you're bound to be impressed, if not pleased. After all, this is your area of daily work and it is being clothed with academic dignity. But what happens to your chosen medium in the process?

Well, here's the way one professor from a mid-west university described part of his course: "Discussion proceeds from cross-generic contrast among documentary, fiction, and experimental films in terms of their ascending order of abstraction from reality as generally perceived."

Now what do you suppose old-timers like Woody Van Dyke or Mickey Neilan would have said to that?

What film critic Pauline Kael said at the conference was, "If you think movies can't be killed, you underestimate the power of education."

Miss Kael had a point, barbed with her usual wit. But if she really believes education can kill the movies, what she's underestimating is the enthusiasm of the younger generation. Let me tell you why I think so.

A year after that film conference I was invited back to Dartmouth for the spring quarter as a visiting lecturer in drama drama being, in this instance, a euphemism for the less academically respectable subject of movies. Dartmouth's one current film course was launched three years ago in response to a petition by 200 undergraduates, with the Nicholas and Pansy Schenck Foundation picking up the tab for a trial period. It is described in the catalogue as English 84 and has been conducted with skill and devotion by the veteran exhibitor and film historian, Arthur L. Mayer, who despite having passed his 80th birthday also manages to lend his charm and wisdom to similar courses at U.S.C., U.C.L.A., Columbia, and a few other institutions of higher learning.

More than fifty students were enrolled last spring and met for two-hour sessions twice a week. It was my uncomfortable but rewarding task to cope with the questions and discussion which followed Mr. Mayer's lectures and to guide the production of student films, thirteen of which were completed in the ten-week period by those who elected this difficult chore in lieu of term papers.

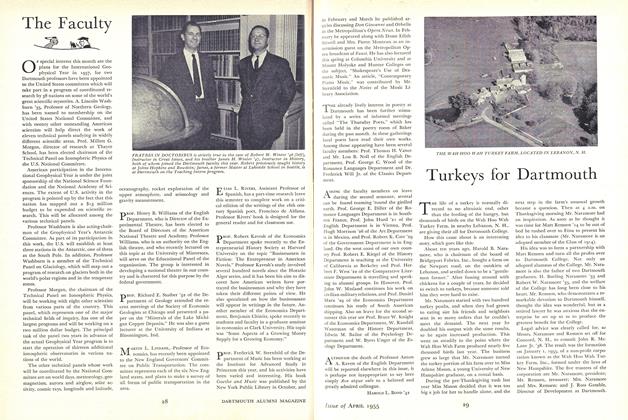

On Wednesdays - weather at Lebanon Airport permitting - there were scheduled visits to the campus by representatives of the film industry. Students (and interested members of the community) met with directors Willard Van Dyke, Shirley Clarke and Don Owen, with Jack Valenti, actress Shirley Knight, producer Gene Persson, and United Artists vice-president David Picker '53. There were also sessions with unexpected visitors like actor Robert Ryan '32 and with producers Andrew and Virginia Stone, whose son was enrolled in the class.

Forty-three feature films were shown, either in connection with the course or as part of the Dartmouth Film Society, whose series this spring was called FromGriffith to Godard. All of these were in addition to the current fare (usually two or three films a week) at The Nugget. Since students could select from any of these films to write their required one review a week, those of us who read reviews felt obliged (though not quite able) to see them all.

Of the more than seventy films available during the eleven-week period, no less than six were judged by one or more of the student reviewers as "the best film' they had even seen, and for some students, at least, this torch of preference passed several times during the quarter from one film to another.

Some of the "bests," if you're interested and if I recall correctly, were A ThousandClowns, Citizen Kane, Dutchman, B½,The Third Man, and, for one boy, Dr.Zhivago.

If these preferences seem unduly volatile, let me say that disapproval was dished out with equal enthusiasm, and some of my own film favorites - classics like Modern Times, The Big Parade and Great Expectations - got mauled in the process.

Here, for instance, is a comment about A Man and a Woman, my choice as the-best film of 1966: "The real difficulty is that the director and everyone else involved with its conception and gestation became too enraptured with one moment of bliss and tried to stretch it over two hours."

On the whole, students were exposed to a pretty fair collection of films, but if most of them didn't give any kudos to Josef von Sternberg's The Devil Is aWoman or D. W. Griffith's Isn't LifeWonderful?, they still got their kicks, as an auto buff does in a museum for antique cars.

What I'm trying to say is that you can't kill the movies for this generation because it's their medium and they love it.

My father, Harry Rapf, was a pioneer producer at MGM, and when I was a youngster I managed, between projection rooms and local theaters (to which I had passes), to see four or five films a week. But anyone of this generation can see more films than that in a single day if he stays close enough to the TV set, and many of them have been doing it since they learned how to get around the family rules against it. So it's their medium and we might as well face the fact that in a few years they'll be running the show.

I don't think I'm indulging in that absurd distortion of contemporary values known as youth worship, though, as columnist Russell Baker has put it, "fifty percent of the population is under 28 and the other fifty percent is trying to pretend it is."

I neither worship youth, nor agree completely with what small part of its values I am capable of understanding. I'm just fond of these young people and think that our medium will be more exciting with a corps of well-trained fanatics fighting their way in.

If I have a major reservation about the ultimate effectiveness of this new generation as a body of film-makers, it .derives from its misconception, fostered by critics and teachers alike, of the auteur theory, sometimes described as "worship of the director." If this sounds like heresy coming from a member in good standing of the Directors Guild, let me point out that I belonged to the old Screen Writers Guild long before I had a chance to give orders on a set and I still believe that the best films are based on the form and content of superior screenplays to which the skill of the director is added.

But a student said to me, "I don't care whether a film has structure or content. I don't really care whether it has anything to say. As long as it has style. And that's the contribution of the director."

Now, a boy like this isn't naive and he knows that when you're raising money for a film in the U.S. you start with a written property which you show to a distributor or backer or to the star who helps you get the backer. And he knows (because we teach this in film courses, too) that there is a step-by-step process predicated on a script which is very important to the financing, to the production planning, and to the finished product. But, he also thinks this is precisely what is wrong with most American films!

Here's what one student said in a term paper entitled "Play to Screen": "Too often the system has been concerned with translating plays, novels, and anything else it can lay its hands on into bank balance and little more. It tends to be more concerned with expanding its wallets than our hearts."

They may sound like smart alecks but they actually do know a lot about films. They read critiques of Kurasawa, Antonioni, and Resnais and you find them tossing around names like Canudo, Bazin, or Jean Mitry (film theorists, in case you like me, didn't know). But films are in no danger of becoming a "dehydrated academic discipline," as Miss Kael claims, because these boys also want to make films and whether the schools offer the necessary help or not, they're going to learn.

What they may not learn or, regrettably, even care to learn is how to tell a story or create character. Dudley Nichols once said, "Character is plot," but they reject plot because they've seen too much of it on TV and to most of them it is shoddy and predictable and unreal. What's to take its place? Technique? Style? The answer for them is "yes" because in the hands of people of talent, it can be used to suggest much more than it actually projects.

And here we come to the crux of it, for it is the medium itself, with its extensions of new style and technique, which causes these young viewers to give of themselves and get reactions seemingly unrelated to an objective analysis of what appears on the screen.

This is skirting through McLuhan territory - the audience being, as he puts it, "part of the show" - but there's nothing really new about that. What's new is the audience itself, brought up in the electric age and exposed to patterns of moving images on a rectangular surface with such frequency in the home and elsewhere that not only are they more susceptible but they are actually tuned to a different wave length of response.

If this sounds abstract and clothed in academic gobbledygook, what it means, in brief, is that for this audience you don't have to lay it on the line - and God help you if you do. They're not only capable of filling in the intervals, of clarifying the obscure, they damned well want the opportunity to do so.

There are no simple generalizations, however. One student did a term project on student taste in films at a variety of colleges and his four volume tabulation put Gone With the Wind and Sound ofMusic at the top of the list.

But at Dartmouth and other schools around the country, an underground filmmaker like Stan Brakhage can sell out a fair-sized auditorium when he appears in blue jeans with his wife and a ninety-minute, 8 mm. film without sound, put together with stock footage, flash frames, Academy leader, and home movies of his children in Colorado. Most of the audience at Dartmouth thought Brakhage was putting them on, but, despite the optical abuse, they didn't walk out and stayed around to exchange insults with him afterwards. And my guess is that it was not so much lack of content as lack of recognizable technique which bothered them.

Among recent American films, the most popular by a wide margin with our students was A Thousand Clowns, which uses a moderately conventional technique to tell a tale about a most unconventional hero, obviously in tune with a college generation inclined to hate the "system." Of the hero, one student review said, "The system has crushed many like him and hampered a good deal of progress, and its agents in Hollywood have been especially vigilant to let as little of worth slip by as possible."

Despite the fact that every character in Clowns borders on caricature, there is something about its style that makes it infinitely more acceptable (and thus believable) than Tony Richardson's LookBack in Anger which is also about a man cause one is English and the other American. More likely, it's because they prefer Jason Robards' good-humored and unpretentious nihilism to Richard Burton's heavy-handed belligerence.

As I come to the conclusion of this article, I realize that its pat journalistic style will offend the free-wheeling sensibilities of the very people it attempts to describe. Tough cookie! I'm not in the classroom now, and the objective has been to tell how it is teaching films to students.

And it's this - that while teaching films can't really kill movies for the students, the experience may just manage to provide new insights about the old medium for you. Sit with a young audience and watch John Gilbert teach Rene Adoree how to chew gum in The BigParade, see what happens to your expectations when the glorious Garbo sweeps through the revolving doors into the lobby of the Grand Hotel, and the next time you start work on a film you may ask yourself, "Am I really going to come across with them?"

My conclusion is that a lot of working members of the film industry should make themselves available for college teaching, though this is really putting the cart before the horse. First, they will have to be asked. And if the colleges are going to keep pace with the demand of the younger generation for film study, they re going to have to raise money for more courses. But when they do - and every sign (including formation of the new American Film Institute) points in that direction - it will not only be good for them and their students, but even better for the film people lucky or wise enough to take part.

Blair Watson (left), who launched theDartmouth Film Society in 1950, shownwith cinema author David S. Hull '60.

THE AUTHOR: Maurice Rapf '35, whogrew up in Hollywood and wrote screenplays for most of the major studios, isnow writing and directing sponsoredfilms as the executive vice president ofDynamic Films, New York City. He wasat Dartmouth for the spring term, assisting Arthur Mayer in the film course.

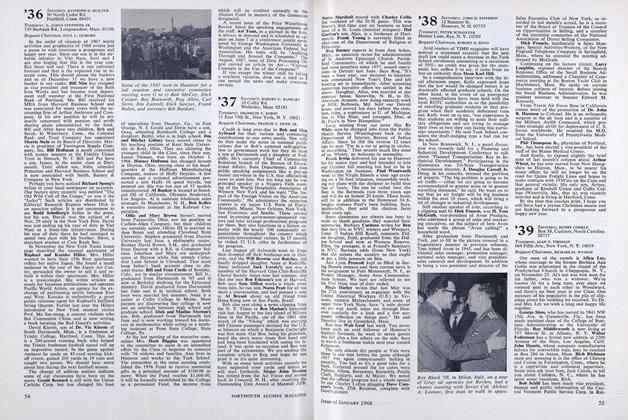

Dartmouth undergraduates shooting amovie in the Hopkins Center.

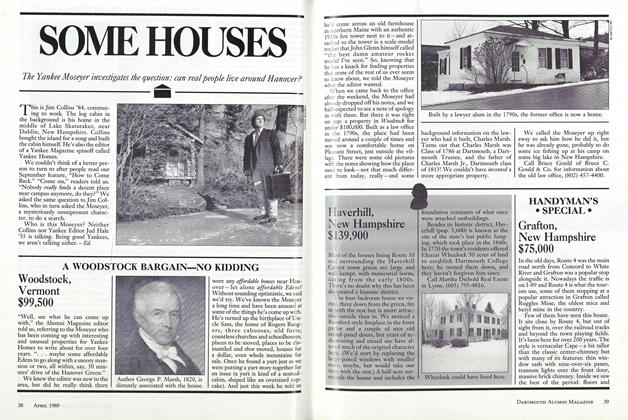

Canadian director Don Owen (rear center) discussing movies with Dartmouthstudents. Author Maurice Rapf and film historian Arthur Mayer are in the foreground.

Three Dartmouth generations were represented in the gift of a Daniel Webster portrait, painted by Edward Savage, to the College Art Collection. It was presented byMr. and Mrs. Gilbert Reynolds Jr. '37 (l) to Prof. Churchill P. Lathrop, director ofgallery acquisitions, in memory of Samuel Quincy Robinson, Class of 1872, andWilliam Marshall Stedman '19, and hangs in the Faculty Lounge.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureEmerson at Dartmouth

January 1968 By Michael L. Lasser '57 -

Feature

FeatureA Lifetime of Theater

January 1968 -

Feature

FeatureAdventures Unlimited

January 1968 -

Feature

FeaturePolice Commissioner

January 1968 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1941

January 1968 By EARL H. COTTON, LOUIS A. YOUNG JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1932

January 1968 By JILDO CAPPIO, ROBERT E. FENDRICH, ARTHUR E. ALLEN JR.