Want to makeyour familyvideos lessboring? Afilm professorreveals thetechniquesof big-timedirectors.

I'VE BEEN INVOLVED WITH MOVIES all my life. My father started producing features in 1916 when I was two years old. A year late began a brief career as a movie actor, playing war orphans, street urchins, and assorted brats. That ended when I started school. My father moved from New York to Hollywood and in 1924 became a mogul at MGM. Making movies was the Kg , family business, and with parental & help, it became mine as well.

The modern camcorder can perform miracles of production on a videotape that can be bought at K-Mart for less than four dollars. And even if you are not one of the nine million who own a VCR to look at old movies, you can still run a cable from the camcorder to your TV set and see little Alex blow out the birthday candles, study the flaws in your tennis backhand, or bore your friends with shaky, handheld images of last summer's cruise. Since this extraordinary instrument has been put in the hands of so many, what can college instructors in film do to provide basic lessons in its use so there can emerge some semblance of technique, aesthetic, taste, and effective communication?

Today's teenager—if unmolested by parental restrictions—has been exposed to as many as 10,000 hours of TV before entering college. (In contrast, when I was a youngster blessed with a pass to local theaters, I managed to see two or three movies a week, and I thought I knew more than most about the medium.) Nowadays, applicants for admission to Dartmouth are apt to send videotapes instead of essays, poems, or short stories as samples of their creative work. These end up in the Film Studies Department for appraisal, much the way a young poet's work might go to the English Department. One applicant for the class of 1994 submitted his 30-minute adaptation of Joseph Comafts Heart of Darkness, a bit ambitious for a cast of teenagers to perform believably but technically quite competent. Because incoming students already know the language by which images and words can be used to communicate, some might wonder what we can teach them.

The answer is that film students are not unlike first graders who can already speak and understand English. In elementary school, youngers learn to put what they want to say in writing; they're taught spelling and grammar the parts of speech and how they are assembled. Same with movie language. A novice can turn on a camera with automatic focus and exposure and get a satisfactory image. The camera, in this sense, is an extension of the eye. And the various shots can be assembled to provide some sort of meaning. It is often said that the shot is like a word, which, when joined to others, forms a sentence. But a shot is more than a word. If you see a gun, the shot says, "This is a gun"— a declarative sentence. But it says much more if someone picks up the gun and points it at another character. What students learn is that the camera does more than observe. In skilled hands it reveals much more than a person can see from a given vantage point—and often in modern sex and slasher movies, more than we want to see.

A simple example: We see a woman open a letter, read it, and smile. We want to know why she smiles. The camera can tell us, if we switch positions and read the letter over her shoulder. Then in the next shot, probably closer than the first, we get her reaction. Three shots to cover one bit of action. A spectacular auto accident might require dozens of shots which create an illusion of ongoing reality even if the elements of the accident are fabricated.

Most movies create an illusion of reality through artifice. We see a girl running from left to right. We see a man also running from left to right. If we join these shots, the illusion is that the man is chasing the woman. Shoot one going left to right and the other right to left, and the assumption is they will meet. There is a grammar to this medium and it is not difficult to learn.

What is difficult, in any language, is having something pertinent to say and the ability to say it in a manner others find interesting. Will Rogers once said everyone has two businesses—his own and the movies. What he meant was that everybody thinks he has better ideas for good films than people who make them. The truth is you can make movies about anything—even little Alex blowing out the birthday candles— if you use movie language to create audience interest. (Example: Shot of the cake as the candles are lit, close-up of dining room with cake, hear "Happy Birthday" sung and see young guests singing, cut to Alex with cake in front of him as he blows, sound of applause, then the knife making its first cut, etc.) Not very exciting, but you are using a sequence of shots to reveal step by step the outcome of a simple event.

Students brought up on TV seem to have a built-in awareness of what can create audience interest. Student proposed subjects such as an eccentric grandmother, the janitor in Butterfield Hall, and frisbee-throwing on the Green can be interesting if given a structure—that is, a problem that needs solving, a question requiring an answer, a conflict in search of a resolution. (At the other extreme, some students influenced by the impact ofMTV propose subjects with random images, heavy rock scores, and no recognizable content at all.) In last summer's documentary class, we had, among the nine offerings, one on dowsing in Vermont (The issue: Is success based on myth or fact?), one on glassblowing in Quechee (The question: How to do it?), and two current controversies abortion, and discrimination against gays in the campus ROTC. Although shot with camcorders, these were certainly not home movies. But like home moviemakers, students find it painful to cut their hours of shapeless mate

rial, to organize it and pare it down to an entertaining and informative short presentation not exceeding 15 minutes. For young filmmakers, for any filmmakers, cutting precious scenes they have sweated to record is like amputating a leg. Cutting, however, is better than causing the gangrene of audience boredom.

I know of few other undergraduate learning experiences that equal this pressure to complete and expose creative work to an unfamiliar audience. Even so, I've never heard a complaint about a requirement which comes so close to duplicating the kind of ordeal one will have to face in the "real" world. And therein lies the appeal. Since enrollment in production and screenwriting classes is limited, we give preference to those majoring in film studies. Still, each term there are applicants from unrelated fields—who want at least one undergraduate course that allows them to do creative work. Some of these newcomers get "turned on," which leads to drastic changes in their career objectives—and justified concern by parents. It is a marvel to me that so many parents of these errant youngsters ultimately accept their decision to chuck job security for the uncertainty of the media rat race. But there are parental rewards—when a son wins an Academy Award as Peter Werner '68 did in 1976, or when a daughter's name appears as a co-producer of "The Great American Air Race of 1924" on PBS (Pamela Mason Wagner '81). If I had the space I could cite dozens of such accomplishments, some of which first come to light when I sit through the interminable credits following a movie or TV show. At the end of my favorite movie last summer ("Dead Poet's Society"), for example, there was B. Thomas Seidman 71 listed as an assistant director. A few months later, I saw his documentary, "Lost Angeles," on PBS.

Only a. handful of those who take film courses, however, are headed for careers in film, video, or the performing arts. What they get, in the liberal arts tradition, is an understanding and appreciation of a major cultural phenomenon of our time. It is, after all, a tough, highly competitive field. Movie and TV companies do no campus recruiting and provide no training programs. My pragmatic advice to budding filmmakers is to go to the Tuck School, get a starting job at 50 thou, make a bundle, and then buy into the business, starting at the top. No one takes the advice—sound as it is—because filmmakers are a special (and wonderful) breed more interested in finding satisfaction in their work than in making money.

Maurice Rapf '35

Features

-

Feature

FeatureSargeant Heads Alumni Council

JULY 1968 -

Feature

FeatureEqual Opportunity

April 1975 -

Feature

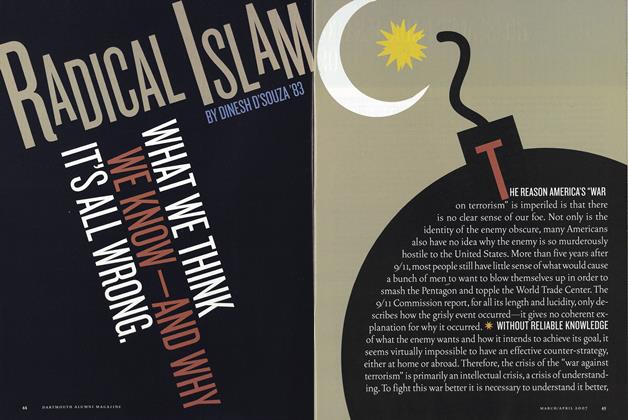

FeatureRadical Islam

Mar/Apr 2007 By DINESH D’SOUZA ’83 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Cutting Edge

May/June 2011 By JULIE SLOANE ’99 -

Feature

FeaturePeace Corps Professor in Bolivia

DECEMBER 1965 By ROGER C. WOLF '60 -

Feature

FeatureThe Quiet Good Man

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Young Dawkins '72