The joys of Dartmouth students 140 years ago definitely did not include permissive parents

DARTMOUTH fathers still hang on to junior's purse strings, but their grip is loosening. Bright sons pick up scholarships. Working summers, mobile sons buy autumn cars. Bookish sons earn money as library assistants.

In the 1820's Dartmouth undergraduates were different, and so were fathers. Sons wrote letters to mother about clothes and to father about allowances, strictly controlled.

Consider Father Hoit (1778-1859). General Daniel Hoit of Sandwich, N. H., expected an exact accounting of the small sums he sent his son William, Class of 1831, later a clergyman-lawyer, and his son Albert, Clas„s of 1829, later a portrait painter. William assures his father that the $10 will be "satisfactorily accounted for." He does not elucidate about "some disturbances in our class which are now done away with." Letters home are filled with information father and mother would like and are silent about escapades.

Sartorially minded, William attempted with adroit flattery to foster an amiable mood in his father. He trusts that his father will give him "the honor of attending Quarter Day May 20." "The coat I now have will be all I shall want. It remains the same as it was at home, not having used it any, but I have no vest or pantaloons suitable. You are undoubtedly willing that I should procure them. I should prefer to get them made here — as I could get them quite as cheap - have them elegant and suitable which cannot be had in Sandwich. I will keep them for handsome clothes, with much care and neatness."

As father, businessman, an officer, General Daniel Hoit had to be handled with filial tact and trepidation. Owner of a store for 50 years, he was the great man of Sandwich. The son of Joseph Hoit, a lieutenant in Stark's regiment at the Battle of Bunker Hill, Daniel was active in the militia, rose from lieutenant colonel to brigadier general. A Selectman almost continuously from 1808 to 1822, he was State Senator in 1828 and Councillor for many terms.

Hence the illuminating postscript penned timidly by a dutiful son hoping sartorially for the best. If belatedly, he would like his father to know that he is a serious student interested more in ideas than in personal adornment. "P. S. I have had an 'Ethical Discussion' with Mrs. Brown's son Gilman on the subject 'Does the experience of mankind prove that the progress of the arts is favorable to national morality?' " Juxtaposed with "national morality" is the need for footwear. "My Old Boots have been mended twice and have now given out in two places. I want some shoes very much. I have none now. I can procure a good pair here for 9/ [about $1.75] - with your leave. I need them much and wish you would either send me some or permit me to get a pair made here."

Home boots were good enough, the General decided. When they arrived, William wrote his mother that he could not possibly get them on, for they were too small in every way. He was "really sorry," for he needed "a pair of boots very much, and they charged 37½ cents for bringing it." William expresses additional disappointment, for his mother had failed to send him some bedsheets which he also needs "very much."

In early 19th-century Dartmouth, undergraduates were kept in line by double control, parents and college administrators. When Albert was 18, a sophomore, General Hoit sent President Tyler a letter via his son with an enclosure for his son. "Dear Albert: Enclosed is the communication for President Tyler which you will not fail to hand him without loss of time. Be prepared to meet the worst, by a fixed resolution to redeem your character by diligence & perseverence in studies and a total disregard for company which may in the least degree lead to idleness and dissipation. And, my dear son, you have only to will it and it can be done, with the smiles of a kind Providence whose smiles I above all things advise you to implore. I expect much of you. Your mother & sisters and your friends expect much from you. Let not their expectations fail. In the bowels of love, Your Parent, Daniel Hoit."

The first part of the letter General Hoit sent to President Tyler was crossed out, but it is still legible. A cross-examination of Albert led the father to believe that the President had given his son permission to absent himself from classes. The rest of the letter is a defense of the debts Albert had run up and a complaint leveled against the college administration for permitting hucksters to prey on innocent students.

The General can hardly believe that his son could be much at fault. "I know not how far my son has gone astray but wish his conduct may be examined minutely. No person was ever freer from dissipation previous to his college connection, and you must be sensible nothing can give a parent more regret than to expend so much to fit his child for usefulness to have it prove his ruin."

The General warned that the reputation of Dartmouth and Hanover would suffer unless this evil were arrested. Minors should not be given credit by local shopkeepers without the written or verbal consent of parents or guardians, "especially for such articles as are usually obtained." "It's immoral - It's unjust, and every person living in the CollegeVillage who practises this course not only should be censured but prosecuted. We had better have a college located among the barrens of the White Mountains out of the way of temptation to dissipation."

Today Dartmouth fathers worry little about how many classes their sons cut; 19th-century fathers worried a lot. Albert Hoit had to account to his for all absences sencesand to assure him that he had reformed. As a senior, he wrote "Since I confired [sic] with the Faculty, which was before President Lord wrote to you, I have not been absent a single recitation or prayer without excuse. I saw President Lord on the subject. He said that the faculty had seen in me a manifest intention to observe the laws of the college in that respect, and, all things considered, I should continue until June. Since the decision I have not been absent or tardy a single exercise nor do not mean to be. With regard to going to Windsor Bank, it was a subterfuge to get leave of absence. Nothing further criminal."

THE discomforts of dormitory life in the 1820's are in sharp contrast to the mechanized luxuries of the 1960's. One student, named Harrison, "very punctual and studious," had to leave Brown Hall "on account of the Pyroligneous [sic] acid which in such large quantities runs from the stove. All the rooms are forsaken."

Even in subzero weather, heating nowadays is rarely a problem, but it was in the early 19th century. William begged his mother to put pressure on his father to send him some money for firewood, which his roommate Woodward had bought with the understanding he should pay half. Despite two requests the General failed to come through. Would mother please mention again that "the sum will be small and ought to have been paid before, that the quarter-day expenses were somewhat more than fie considered and that there are a few other little incidentals for which a very small remittance would be acceptable and most gratefully received."

Apparently Mrs. Hoit had insufficient influence, for some three months later William wrote peremptorily, "... I wish him [Pa] to enclose money in his next letter for me to pay Woodward - and a little to defray the expenses of Quarter Day etc. etc."

As a Dartmouth senior, William wrote with passionate submissiveness to ask for money and clothes to protect him against the forthcoming winter. He describes himself as being "rather destitute." He had accidentally sent home an old pair of blue "pantalloons" reserved for emergencies. The pair he had on are worn "somewhat thin for cold foggy mornings and the chillness of autumnal atmospheres." The seat, a "little the worse for wear," had given out twice since he left home. His cloak is so worn out in the seat as "to render it utterly unfit to wear." His father must not delay. "The keen northern blasts that whistle through the multitudinous cracks and crevices of those old venerable halls of literature and science force home upon me the painful recollection that I am destitute of the 'wherewithall' to wrap my corporeal syspheres."

To make the "urgent importunity" and "absolute necessity" more compelling Williams describes his health. "I am troubled with a cold & a very severe cough that almost hinders my speaking. The mornings here are intensely cold and raw. . . . Health is emphatically the staff of life . . . and he who wantonly subjects it to an useless exposure positively sins against his duty — to himself and his Creator."

Two weeks later the clothes so passionately urged arrived "safe and in better season" than William had expected. It would be difficult to adjudicate between his gooseflesh and his dismay when he tried on what had the highest priority, the pantaloons. "A waste of cloth and a waste of money," too long and too large, they might be a good fit for a man twice his size. The old ones had to be patched again.

His profound sartorial disappointment led him to comment philosophically about the death of a close friend and his friend's bride. "O! how brilliant are our fond anticipations of the future; everything looks higher and unsullied. Life seems an eternity of uninterrupted happiness, the world a paradise of unmingled pleasures, and in the buoyancy of youthful spirit we put off the evil day, but the cold hand of death blasts everything beneath its withering touch making no distinction of persons or things. A Lesson upon the vanity of life that should never be forgotten.... I left him in perfect health. When I return home, his body will have crumbled to dust and mingle with its native earth. The soil of the valley will cover him and the places that have once known him will know him no more forever, and his eternal, immortal spirit - where will that be? O! dark and uncertain is futurity. . . . The bell is tolling for prayers, and I can write no more."

THE Hoits controlled their son's vacation movements with a severity incredible to a modern Dartmouth undergraduate. William requested permission from his mother to return home to Sandwich by way of Concord. Explanation: he had never taken that route and had not seen Concord in six years. "The cost will be but little, if any, more, and it will be much more pleasant to me, and I hope you will consent to it."

He also sounded out his father about leaving Hanover early. "My room is cold, am out of wood which is scarce and dear, studies are at present dry and uninteresting, and most of the students have left the plain." He badly needed $8 and hopes that his father will send the money quickly.

On another occasion William felt obligated to explain to his father that an outing to Newport to visit his brother Albert had cost nothing and had had worthwhile advantages. He acquiesces in his father's assumption that the pleasure of the ride and a fraternal visit could not have been condoned if it had cost something. "The stage fare was nothing since both stages were anxious to carry me and give me my board on the road though I generously excused them from the latter; as the distance was short, I felt no hunger. I went to A's [Albert's] boarding house so that the [dinner] cost me - nothing - rather tolerable visiting, I thought."

Today Dartmouth students rely on long-distance-collect calls as a medium of communication with parents. Blessed with more time and with epistolary facileness, 19th century students depended on letters. Aged 17, a junior, William assured his mother that in a desperate illness Providence had been kind in sparing him for her - for the time being. "... I have been most shockingly sick but think I to myself I'll say nothing about it to Ma till I get well... this confounded change of weather ... gave me a most shocking cold in the head, and this with a disordered stomach have confined me to my room for several days, but bleeding and physic have at length set me on my feet again, and I venture down to dinner today, but I am still weak and unable to go out much."

William knew how to tug on his mother's heart strings. He touches on his growing maturity and his independent struggle in a cruelly competitive world. In purple passages better understood by maternal rather than paternal intelligence he pulls out all the stops. "In a few more days if Providence spares my life and health I shall no longer be under the kind and protecting care of my dear parents but shall be left upon the stormy and tempestuous occean [sic] of human existence, alone to contend and buffet with the waves and winds and squalls that continually assail the weather-beaten passen- ger in the short passage of life. Whatever course, my dear Mother, I may pursue I feel confident of success, but this confidence is owing to the sanguine hopes and ardent feelings of youth and that time and experience will wither and blast those golden prospects of futurity and the nipping frosts of age will palsy the kindly feelings of the heart, and blight the ardent aspirings of young ambition. But it is useless to gaze continually at the dark side of the picture; life is but a dream, and while it lasts we may enjoy it without brooding forever. ... It has many and great purposes to be completed and ... we may happily spend our lives and happily conclude them, without their being darkened by the clouds of remorse or regret for time mispent [sic] and we may leave the world too, beloved by our friends, by mankind, and by God."

If few modern undergraduates find time to write parents, still fewer brothers ever write to their sisters. In the 19th century long letters were frequent. In keeping with his 17-year-old maturity, William adopted a facetious, sophisticated, and condescending tone in writing to his sister Julia. He has "exhausted his unprolific brain of every idea" and "nonsense is the order of the day." All from wealthy aristocrat down to kitchen maid prate incessantly of what they know nothing. They put the most stylish clothes on their "spindle shanks," tie their "cravat" in the newest mode, wear beaver hats, dash on Cologne "with an eternal simper of self conceit," - all, i.e. except her brother William and other poor College devils "whose brains, steeped in Greek-Latin and (last, but not least, lamp oil) are as musty as the venerable and worm-eaten folios over whose musty pages we pore at midnight hours, wasting the spring time of life, the buoyance of spirit and the glow of health, must drivel on, unnoticed and unknown."

With something less than absolute logic William assures Julia that he has fathomed the motivations of women. He boasts that he has become "that pink of pinks - a beau ... a favorite with the fair of Hanover." He has gone to "parlor parties" in which "are assembled certain painted peices [sic] of frail flesh ... all vie with each other in talking nonsense." He proudly asserts that he has "learned the secret of fulsome, despicable flattery - so dear to women's hearts . . . the soft insidious whisper of slander and detraction, so sweet, so passing sweet, so deliriously intoxicating to the lady's ear - and to favor and smile with the smooth honied face of hypocracy [sic] upon those whom from my very soul I loathe and detest."

With charming linguistic restraint the brother, not yet 18, assures his sister, who is, he says, "a black-eyed, rosy-cheeked, auburn-haired lassie" that he "has learned the art of arts, the great art of pleasing fond, foolish woman, who with all her faults is an angel while men are - I had almost said - d - Is."

After such lofty idealism and Byronic cynicism, the Dartmouth junior in a postscript asks Julia to pay a bill of $1.75 for him if she should have money enough. He promises to reimburse her promptly during vacation. To soften her up, he promises her another beautiful little kitten.

THE Honorable Daniel Hoit kept tight control not only of his sons' finances but also of their vacation employment. Even though pay might be wretched, schools inferior, and continuous college residence important, the General acted unilaterally. As a senior, Albert was informed that he must take a teaching job for the winter term. Often a benevolent go-between, William wrote his father that Albert could not accept it and offered himself as substitute. In a postscript to William's letter Albert, ignoring his brother's placating style, wrote in a bold hand, "Dear Father, It is impossible for me to take that school. The Government [i. e. the College Administration] will not permit it.... Prof. Adams thought it indispensable that I should stay here all the term."

General Hoit also signed on William for a teaching job without consulting him. With filial deference William objected that it would entail returning late to college with final examinations, supremely important, taking place a week after term opened.

William objected to paternal pennypinching. "As for boarding at home ... it will be almost impossible — to walk 2½ miles in the morning after breakfast. I should not have time to do that unless our folks get up & get it sooner than they commonly do. Then I should have to walk the same distance after school and face those horrid cold winds upon Wentworth Hill. I should earn only 10 or 11 dollars for all my work [full-time teaching for a month], a sum hardly worth coming home after."

Gently tactful, William observes that it was "rather strange" of his father to engage him for that school despite his often expressed aversion to it because of its low standards. It would be "almost insufferable" to teach such "backward pupils" among whom would be found no inquiring minds. "After studying a long term of 14% weeks, it would be a poor respite to teach that school for $10 a month & board at 2½ miles from the school house."

Such unimaginative parental tyranny finally aroused William's anger. "I inherit from you a goodly portion of pride, of honest pride, and it galls me, touches me to the quick, to think of keeping that school for $10 a month. What a contrast between that sum and the wages I might have had in Stoneham, Mass., with $23 a month. I tell you, & tell you honestly & frankly, Dear Father, .. . that I feel somewhat neglected in not having my wishes at least consulted in such an engagement."

His flash of anger burning out, William again proved himself a dutiful son. "But if you cannot get off on honorable terms, or indeed if you do not choose to get off at all, I will come home and commence the school the first Monday in January, or, if the term should close a few days sooner, I can commence a week sooner."

Less docile and more fiery, Albert upon reaching 21 made up his mind that he could not knuckle down to teaching and must quit it and New Hampshire, to devote himself to portrait painting. In Rochester, N. Y., he found "great encouragement given here to the fine arts, and it is a large and flourishing place - besides being very pleasant. I am as steady, sober, and industrious as the best could wish."

Flooded with commissions in Portland, Bangor, and Belfast (Maine), St. John's, New Brunswick, he moved on to Wash- ington and gained such prestige that Salmon P. Chase, Dartmouth 1826, engaged him. Statesman, Secretary of the Treasury under Lincoln, and Chief Justice during the Reconstruction, Chase had been bored to death with applications from all quarters to sit for portraits and busts, and with one or two exceptions he had refused. A tall man, with large head, deep-set blue-gray eyes, spirited nostrils, firm lips and a distinguished figure and bearing, Chase had fascinated painters who found him elusive to capture in paint.

Daniel Webster treated Albert "very civilly" and at once gave him "a very handsome letter to Gen. Harrison," the hero of the Battle of Tippecanoe and the ninth President of the United States. And so as a fashionable and competent portrait painter, Albert moved into the world of the great and near great. A year and a half in the galleries of Italy, France, and England enlarged his horizons. Boston became his permanent home. He died there in his 48th year.

More emotional in his undergraduate letters than Albert, William had lofty ideals about character and conduct. "I shall make, dear Mother, no hasty promises or asservations ... I may become the vilest sot that ever reels home to his miserable and wretched family or the veriest scoundrel that ever defrauded justice of its due, but if good will towards my friends, mankind, and myself, purity of intention, fineness of resolution, and industry and perseverance to carry into effect can do anything, I may succeed."

Graduating from Dartmouth, he read divinity at the Andover Theological Seminary, was ordained an Episcopal Deacon, became converted to Roman Catholicism, studied law, and practiced in St. Albans and Burlington, Vermont. He lived to be 70.

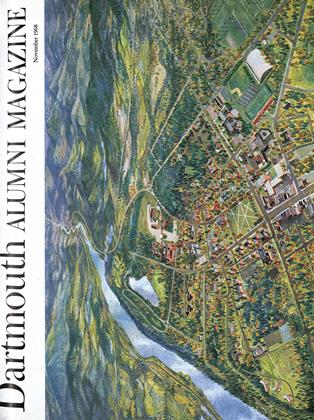

An artist's depiction of Old Dartmouth Row as it appeared about 1830.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTHE VICE VERSA VIRTUES

November 1968 -

Feature

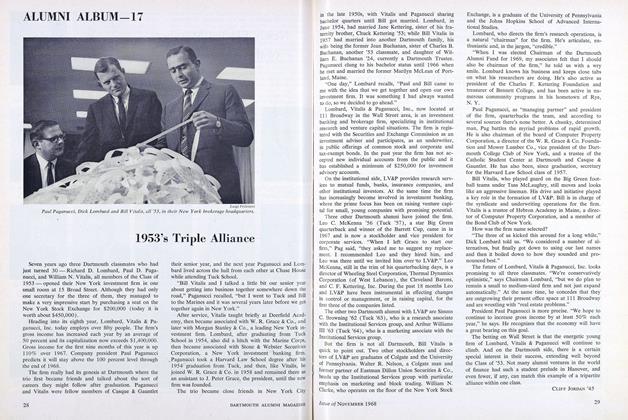

Feature1953's Triple Alliance

November 1968 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Feature

FeatureANOTHER COLLEGE YEAR BEGINS

November 1968 -

Article

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

November 1968 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

November 1968 By RICHARD K. MONTGOMERY, C. HALL COLTON, THOMAS E. WILSON -

Article

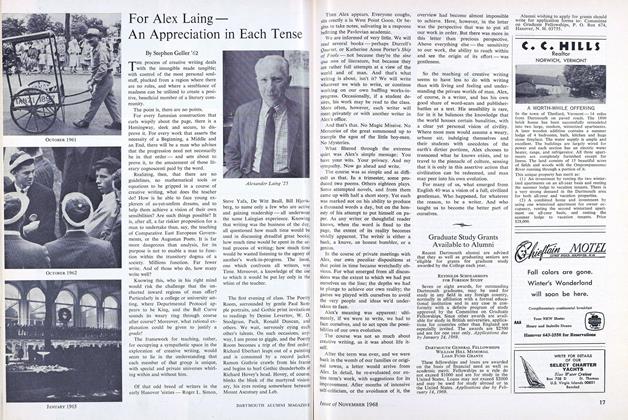

ArticleFor Alex Laing – An Appreciation in Each Tense

November 1968 By Stephen Geller '62

John Hurd '21

-

Books

BooksFEEL FREE.

DECEMBER 1971 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksARCHITECTURE OF THE WESTERN RESERVE, 1800-1900.

FEBRUARY 1972 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksDOUBLE TAKE.

FEBRUARY 1972 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksFurther Mention

MAY 1972 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Article

Article1972 Course Guide

JANUARY 1973 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Article

ArticleEllwood Huff Fisher '21: A Tribute

September 1975 By JOHN HURD '21

Features

-

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Medical Metamorphosis

December 1959 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO WIN AT LUGING

Sept/Oct 2001 By CAMERON MYLER '92 -

Feature

FeatureClassnotes

NovembeR | decembeR By DARTMOUTH COLLEGE LIBRARY -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

Jan/Feb 2012 By Jennifer Caine ’00 -

Feature

FeatureWhen Dialogue Turns to Diatribe

MAY 1989 By Larry Martz '54 -

Feature

FeatureBehind the Scenes

MARCH | APRIL By LISA FURLONG