MAN INCORPORATE, THE INDIVIDUAL AND HIS WORK IN AN ORGANIZED SOCIETY.

November 1968 LAURENCE I. RADWAYMAN INCORPORATE, THE INDIVIDUAL AND HIS WORK IN AN ORGANIZED SOCIETY. LAURENCE I. RADWAY November 1968

By Carl B. Kaufmann '47. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1967. 281 pp.$5.95.

This is essentially a reasoned defense of the large, scientifically advanced corporation in modern America. Its author, a Du Pont executive with varied public relations experience, is evidently familiar with criticisms of business enterprise advanced by unsympathetic sociologists and economists from the New Deal to the New Left. Moreover, he is far too astute to dismiss them out of hand. But his final verdict is that the corporation is "an extraordinarily useful social device." En route to this conclusion he makes clear his own robust faith in hard work, organization, cities, the market economy, and modern technology. And he turns the tables rather deftly on liberal 'academicians by emphasizing phasizingthe institutional conservatism of the university.

The first half of the book includes a set of four highly condensed historical essays. The first deals with the development of economic institutions and makes a case for the superiority of large, specialized business enterprises. The second is a history of technology, one moral of which is that inventions generate surpluses which support educational and cultural advances. The third, which depicts changing attitudes toward work, defends the dignity of labor against "aristocratic" ideals. The fourth examines the low repute in which trade was often held in former times.

There are some unduly sweeping generalizations here, e.g. that aesthetic and humanistic values thrive best where there is optimum use of technology. One thinks of Hitler's Germany! There are also some highly debatable assertions, e.g. that Marx "cared little for the subjective or moral questions surrounding man's work." On the whole, moreover, this earlier part of the work, despite allusions to such authorities as Weber, Troeltsch, and Pirenne, is less satisfying than the second part, where the author stands or: more familiar ground.

Here I found particularly valuable his account of the increasing importance in many industries of professionals, many with doctorates; the virtual disappearance of un- skilled labor; the declining role of the assembly line; and the power in recruiting of such non-cash incentives as cultural amenities, professional prerogatives (including sabbaticals), and the aesthetic appeal of the neighborhood in which a plant is located.

Because the author apparently hoped to reach a large audience, his book is written simply, perhaps too simply at the start. But its depth and pace pick up with each succeeding chapter and my own judgment is that the work as a whole dispels many more illusions than it creates.

A member of the Department of Government at Dartmouth, Professor Radwayteaches courses in Public Bureaucracy andPolicy Development and Conduct of American Foreign Relations.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Woes of the Hoit Brothers

November 1968 By John Hurd '21 -

Feature

FeatureTHE VICE VERSA VIRTUES

November 1968 -

Feature

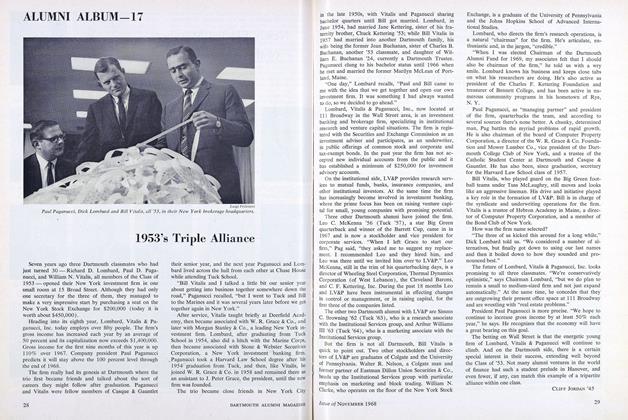

Feature1953's Triple Alliance

November 1968 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Feature

FeatureANOTHER COLLEGE YEAR BEGINS

November 1968 -

Article

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

November 1968 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

November 1968 By RICHARD K. MONTGOMERY, C. HALL COLTON, THOMAS E. WILSON

LAURENCE I. RADWAY

-

Feature

FeatureHow Much Government?

March 1954 By LAURENCE I. RADWAY -

Books

BooksTHE POLITICS OF DISTRIBUTION.

June 1956 By LAURENCE I. RADWAY -

Books

BooksFREEDOM OF SPEECH BY RADIO AND TELEVISION.

APRIL 1959 By LAURENCE I. RADWAY -

Feature

FeatureCITIZEN SOLDIERS

October 1973 By LAURENCE I. RADWAY -

Books

BooksNot in the Stars

January 1976 By LAURENCE I. RADWAY -

Books

BooksThe New Right

November 1979 By Laurence I. Radway

Books

-

Books

BooksThe latest musical composition

MARCH 1932 -

Books

BooksFaculty Authors

November 1944 -

Books

BooksTHE UPPER TANANA INDIANS.

November 1959 By ALFRED F. WHITING -

Books

BooksCORPORATE CONCENTRATION AND PUBLIC POLICY

April 1943 By G. W. Woodworth -

Books

BooksCONTEMPORARY UNIONISM IN THE UNITED STATES

January 1949 By Ross Stagner -

Books

BooksTHE STORY OF PITNEY-BOWES.

October 1961 By WAYNE G. BROEHL JR.