Secrecy in government is as American as pizza pie. In this little book a Hanover-bred author, the son of a distinguished Dartmouth teacher, describes the growth of the "secrecy system" in our country. Separate chapters discuss the shenanigans of the CIA and the cosy relationships between journalists, legislators, and national security officials.

Few of the findings should surprise. Since knowledge is power, leaders are tempted to pursue strategies for its acquisition, denial, and manipulation. In war this drives them to protect their own secrets, to ferret out the other fellow's, and to lie about how their side is doing in order to sustain front-line and home-front morale.

Such strategies were continued into the cold war. Less excusably, the government turned them against its own citizens. The result was informational behavior and misbehavior — wiretapping, news management, cover up, executive privilege, mail opening, burglary - that came to be defined as part of the problem of excessive presidential power.

This in turn provoked widespread criticism of which Cox's book may be taken as a representative period piece. Based in part on inside information gathered during his service in State, CIA, and the White House, it displays much of the sense of indignation currently fashionable in a chastened Washington.

All this is to the good. Yet a few observations need to be added. One is that governments at war may have weighty reasons, if not finally satisfying ones, for concealing from their own people actions known to the enemy. The bombing of Cambodia is a case in point. To reveal it to American citizens would probably have embarrassed the government in Phnom Penh, forcing it reluctantly to break diplomatic relations with Washington; it might have strengthened the hands of hawks in Moscow and undermined the influence of our supporters in a number of allied and neutral capitals; and it might have unleashed domestic demands for a wider war. On balance I believe these risks should have been taken, but the issue is more complex than is commonly supposed.

More important is Cox's contention that "democracy and secrecy are incompatible"; that the President and a few of his top assistants "engaged in a conspiracy against the American people"; and that there is nothing wrong "that can't be cured by employing the essential strengths of our democratic system."

My own view is that the system was the heart of the problem and that Cox's characteristically American optimism is contradicted by his own findings that "stopping the spread of communism was endorsed by an overwhelming consensus" of the public; that Congress passively accepted executive domination; and that the press was "eagerly willing to be manipulated." As was said so well so long ago, "The fault, dear Brutus, lies not in the stars but in ourselves...."

THE MYTHS OF NATIONALSECURITY: THE PERIL OFSECRET GOVERNMENT. ByArthur Macy Cox '42. Beacon,1975. 231 pp. $9.95.

Dartmouth Professor of Government, Mr.Radway teaches courses in The Politics of theExecutive Branch and American Foreign andMilitary Policy.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureOur Way in the World: A Conversation with John Dickey

January 1976 -

Feature

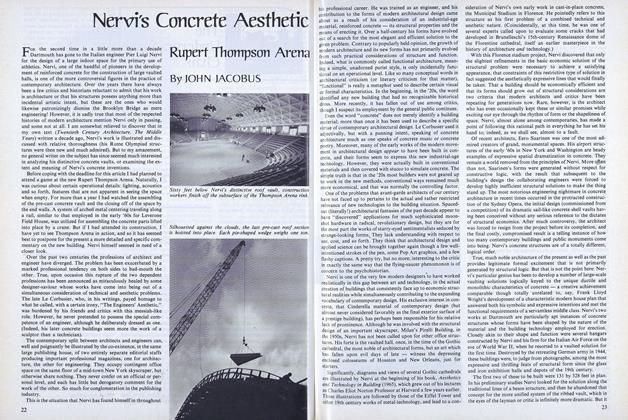

FeatureNervi's Concrete Aesthetic

January 1976 By JOHN JACOBUS -

Feature

FeatureA Season on the Racetrack Special

January 1976 By DAVID DUNBAR -

Feature

FeatureFarewell Dear (BOOZY, BRAWLING) Davis

January 1976 By ROBERT SULLIVAN -

Article

ArticleA Reasonable Balance?

January 1976 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

January 1976 By DOUGLAS WISE, BARRY R. BLAKE

LAURENCE I. RADWAY

-

Feature

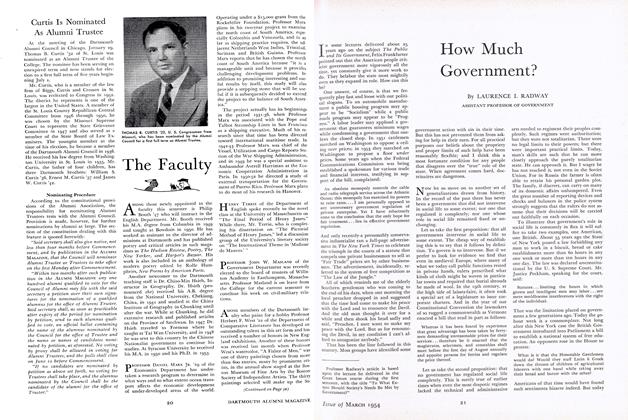

FeatureHow Much Government?

March 1954 By LAURENCE I. RADWAY -

Books

BooksTHE POLITICS OF DISTRIBUTION.

June 1956 By LAURENCE I. RADWAY -

Books

BooksFREEDOM OF SPEECH BY RADIO AND TELEVISION.

APRIL 1959 By LAURENCE I. RADWAY -

Books

BooksFOREIGN AID AND AMERICAN FOREIGN POLICY: A DOCUMENTARY ANALYSIS.

JANUARY 1967 By LAURENCE I. RADWAY -

Books

BooksMAN INCORPORATE, THE INDIVIDUAL AND HIS WORK IN AN ORGANIZED SOCIETY.

November 1968 By LAURENCE I. RADWAY -

Books

BooksThe New Right

November 1979 By Laurence I. Radway

Books

-

Books

BooksThe Underside

October 1980 By A. Roger Ekirch '72 -

Books

BooksTHE CAUGHT IMAGE.

JULY 1964 By HENRY L. TERRIE JR. -

Books

BooksJOURNEY OF A JOHNNY-COMELATELY.

November 1957 By HOWLAND H. SARGEANT '32 -

Books

BooksPSYCHOLOGY THROUGH LITERATURE

June 1943 By Irving E. Bender -

Books

BooksDIDEROT, THE TESTING YEARS,

July 1957 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksPolitical Pluralism

MAY 1983 By Russell D. Hemenway '49