Did the critics - and the war in Vietnam - kill ROTC, or is there life off campus?

ROTC has been part of the educational landscape for more than fifty years. Units exist at several hundred American colleges and universities. Yet some members of the academic community have long been critical of the program on educational grounds. Campus skeptics are inclined to describe ROTC courses as "guts" or to dismiss them as "Mickey Mouse," devoid of theoretical interest, laden with trivia, and unworthy of academic credit. If pressed, liberal arts purists will concede that instruction in navigation or military courtesy is no more inappropriate than instruction in welding or photojournalism, and that viewed solely as an intellectual operation, stripping a Browning automatic rifle is not fundamentally unlike dissecting a cadaver. But to the critics such parallels do not redeem ROTC. For they contend that vocational training has no place in a liberal education and that professional education best follows the baccalaureate period.

Campus critics are also restless about the quality of ROTC instructors and the nature of their teaching methods. Material is said to be drilled into the hapless student in a fashion derived from age-old efforts to provide routine skills to masses of poorly educated enlisted personnel. The instructors themselves are felt to possess less intellectual distinction than their civilian counterparts. Less often but perhaps more tellingly, they are compared unfavorably with more promising military officers. Why, it is asked, are so many incoming heads of ROTC units starting their last tour of duty before retirement?

More recently, concern has been expressed that ROTC may jeopardize the autonomy 'of its host institutions. Under federal law, it is noted, no unit may be retained at a university unless the latter adopts, as part of its curriculum, a course of instruction "which the Secretary of the military department concerned prescribes and conducts." In most cases the services determine the subjects, syllabi, and teaching materials used in ROTC courses. The Navy does not permit its ROTC students to major in certain fields not deemed useful to a naval officer. Host institutions are also required by statute to award the rank of professor to the senior officer of each ROTC unit. He thereby acquires faculty status although he is not paid, evaluated, reappointed, or promoted like other faculty members, and in practice he is not recruited like them.

The conclusion has been drawn that ROTC units resemble "foreign embassies within otherwise sovereign territory." This analogy acquires more bite when it is observed that the staffs of these particular "embassies" operate not only on the technical skills of the "natives" but on their belief systems, and that they aim to develop attitudes aboutnationalism, discipline, and obedience, which members of the "host country" do not necessarily share.

It would be nice to report that campus complaints were ordinarily accompanied by constructive suggestions for improvement. Such, unhappily, has not been the case. Nevertheless, in the past few years ROTC has been modified in ways which seem to take into account some points made by critics. One or another service has introduced two-year programs, accepted cuts in academic credit, invited civilians to teach designated courses, reduced drill requirements, or settled for less than full faculty status for instructors. If they have not responded immediately to every considered criticism, the armed forces have given more ground than is commonly supposed; and with in- genuity, imagination, and good will on all sides, it is conceivable that they could meet many of the objections to ROTC raised on educational grounds.

The Political Context

The intensity of recent anti-ROTC sentiment, however, leaves little doubt that it was inspired mainly by opposition to the Vietnam war. Such opposition was particularly strong at well known schools. All ROTC activity was ended at Brown, Dartmouth, Harvard, Stanford and Yale. Air Force and Naval units were discontinued at Princeton; the Army program was also terminated, but it was reinstituted a year later with the understanding that a 'final" decision about its status would be made in the autumn of 1973.

While most campuses chose to keep ROTC, two major developments began to affect enrollments adversely. The first was that many institutions which had had compulsory ROTC began to make it voluntary.* The second, which paralleled the disengagement of American forces from Vietnam, was a drop in the draft calls that had driven so many undergraduates to the ROTC refuge in the first place.

Confronted with these challenges the services made vigorous efforts to protect themselves. The Army increased subsistence allowances for advanced students; it liberalized course offerings; and it inaugurated an intensive public relations campaign. In 1969 the Benson Committee, a high level Defense Department panel, reminded host institutions that they were free to organize ROTC as a "program" or a "center" instead of a department, that they could increase the proportion of civilian instructors, and that they could transfer more drill to summers.

But there were limits to what the Pentagon could offer. For if it was confronted on the one hand by an increasingly suspicious academic world, it was confronted on the other by members of Congress who were in no mood to "reward" prestigious academic institutions for their "transgressions." The House Armed Services Committee had begun its own study of ROTC after the campus outbreaks in the spring of 1969. It concluded that if ROTC were attacked at any institutions, the government should not only cancel the program at once but withdraw all defense contracts from that institution. A week later the Army announced that it would terminate ROTC at Harvard and Dartmouth, whose faculties had voted to phase out the programs as currently enrolled students completed them. Army officials were later to observe pointedly that dozens of other schools were eager to move in if the Ivy League moved out.

Questions of quality aside, the new institutional participants obviously did not provide students in the quantity necessary to stabilize ROTC programs at previously existing levels, for enrollment fell from 260,000 in the fall of 1966 to 75,000 in the fall of 1972. Whether it will continue to decline will depend on several factors, among them the advent of an all-volunteer armed force. The end of the draft was announced midway through the academic year 1972-73. If Princeton's experience is representative, it is not reassuring. Twenty-eight draft eligible sophomores were enrolled in Army ROTC in September 1972. By the end of the academic year more than 50 per cent had dropped out.

The Larger Issue of Civil-Military Relations

The prospect of a curtailed ROTC program raises major issues of civil-military relations. Two themes ran through the Benson Committee's report on this question. One defended the utility of a blend of civilian and military values to be secured by exposure of students to both "highly motivated" officers and "critical thinking" civilian teachers. The other was that removal of ROTC from campuses might isolate the services "from the intellectual centers of the public which they serve and defend."

Several observations must be made about these contentions. First, it is true that civilian universities produce a large part of the American officer corps. In 1970 more than 25 per cent of Army generals on active duty were ROTC graduates. It is also true, however, that the retention rate for ROTC graduates is below that of service academy graduates, and that the latter still predominate at the higher levels of all services, especially in the Navy. Second, removal of ROTC from campuses will not necessarily isolate the services from educational centers. The service academies regularly recruit young instructors who have studied at civilian universities, and during their careers most regular officers will be assigned to civilian universities for graduate work. Third, while interaction with officers may have been a valuable educational experience for some ROTC students, it has been a disillusioning experience for others. Invidious comparisons are probably more common when military and civilian programs coexist on campus than when they are conducted in separate locales. Fourth, the need for this particular technique of checking and balancing the power of an officer corps is probably less in the United States because officers are divided among four highly competitive services, and because they lack the power and prestige which their foreign counterparts derive from membership in a privileged social class. European cadet schools often became citadels of an established elite. America has long delegated to a representative legislature control over most appointments to its service academies.

Nevertheless, most Americans would probably agree that it is wise to recruit officers from a variety of sources, and at least one social researcher concludes that ROTC products "appear to be less absolutistic, less belligerent, and less militaristic than either the non-college or the service academy officer."

Off-Campus Options

It is another question, however, whether ROTC, with its many educational and political implications, is the only or the best way to recruit graduates of civilian institutions. This issue invites attention to off-campus alternatives.

Some of these were explored by the Benson Committee a few years ago. For example, it examined the Officer Candidate School program, only to conclude that ROTC was a better source of quality officers. It also looked at the "platoon leaders" program of the Marine Corps, which requires students to devote two months to summer trainins. But the Benson Committee argued, not very convincingly, that this approach would be impracticable for the other military services. A plan was considered under which the regular academic year would be unencumbered by drills or by any ROTC courses except those taught by civilian faculty members. But the conclusion was that such an approach would fail to supply a continuing blend of civilian and military studies; it would inconvenience those students who might not wish to devote an entire summer to military training; it would require too much postcommissioning instruction; and it would provide too little on-campus contact to develop students' interest in military careers. Yet another variation envisaged instruction in routine military skills at off-campus centers while host institutions assumed responsibility for an educational concentration embracing their own concept of the ideal officer. The Benson Committee concluded, not very decisively, that this proposal "apparently has some merit and could at some time be put to partial use." Finally, with the model of a French training program in mind, it considered whether students might supplement daily civilian studies with training at military installations during weekends. The difficulty here, the committee report said, was that American colleges are widely scattered, "often miles away from significant military installations, so that such a plan would be feasible only in a few metropolitan areas."

One emerges from all this with the impression that the Defense Department simply did not think the time ripe, or the need sufficiently great, for major change. Certainly its analysis did not do full justice to the prospect of evening or weekend training away from campus. It is possible, for example, to envisage a network of Regional Officer Training Centers - to preserve the traditional ROTC initials - located at public facilities such as schools or armories. The transfer of units to such off-campus sites could permit dissolution of the somewhat unstable compound of training and education which characterizes present ROTC curricula. It would do so not, however, by making ROTC courses more "civilian," an effort which sometimes produces the worse of both worlds, but by making them more "military." It would permit the services to substitute a contract with individual students for a contract with their institution. The university could continue to call attention to the existence of an ROTC option, but its part in the program would be so minimal that campus critics would no longer be able to charge official sponsorship.

An evening or weekend plan could also make the civilian input into the officer corps more representative than it is under ROTC as now constituted. First, it could reach out to young college graduates interested in switching careers. Second, it could include men who are not now attracted to ROTC in sufficient numbers members of minority groups. dropouts, and recently discharged enlisted men with officer potential. Third, the undergraduate component would not have to be drawn so largely from the particular subset of institutions which happen to have ROTC units and which chose to keep them in the face of anti-ROTC sentiment.

The point here is of the utmost importance. ROTC will survive best at southern and western institutions where there is less dissatisfaction with the educational or political implications of the program. It will fare worst at precisely those institutions which produce a disproportionate share of political executives, higher civil servants, legislators, editors, scientists, foundation officials, lawyers, bankers and educators concerned with foreign and military policy. The danger, clearly, is that a shrinking ROTC program will widen the gulf between our future military and civilian leaders. Instead of decreasing and homogenizing the pool of potential participants, there seems to be every reason to enlarge and diversify it.

On financial grounds, also, instead of perpetuating a large number of relatively unproductive campus-based units, it seems sensible to seek economies of scale by creating a few off-campus programs. Moreover, with a little imagination these could be integrated with centers for the training of National Guard and reserve components. Less likely, but not inconceivably, they could promote armed forces unification by providing common courses of instruction before personnel proceeded to the study of subjects peculiar to the individual armed services.

Lingering Resentment

No one can foretell whether or to what extent ROTC will languish in coming days. But it is sobering to recall that anti-militarism has been as much the rule as the exception in American history, that this is the second, not the first, time that the academic community has risen in opposition, and that the earlier attack - between 1921 and 1936 - was probably more broadly based than the present one. It centered not in the Ivy League but in such large state universities as Wisconsin and Minnesota, and at the time approximately two dozen institutions made ROTC optional or dropped it entirely.

But if prudence suggests improved insulation against passing campus storms, other motives and considerations combine to make the Pentagon slow to strike out in new directions. The officer corps, ever uncertain of its status in a liberal society, welcomes the legitimacy and prestige which flow from connection with great universities. A kind of domino theory operates to warn that otherwise viable on-campus units may be undermined in Alabama or Oklahoma if off-campus options are created in Boston or Chicago. And lingering and justified resentment over shabby treatment makes many professional officers reluctant to meet campus critics more than half way.

Nevertheless, large sovereign nations will continue to require armed forces, armed forces will continue to require new officers, and an informed concern for a representative officer corps suggests the wisdom of experimenting with at least a few off-campus centers to provide additional avenues or supplementary tracks to a military commission for the coming generation of undergraduates.

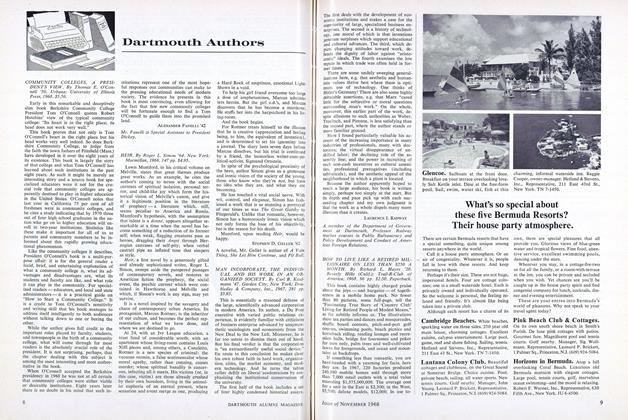

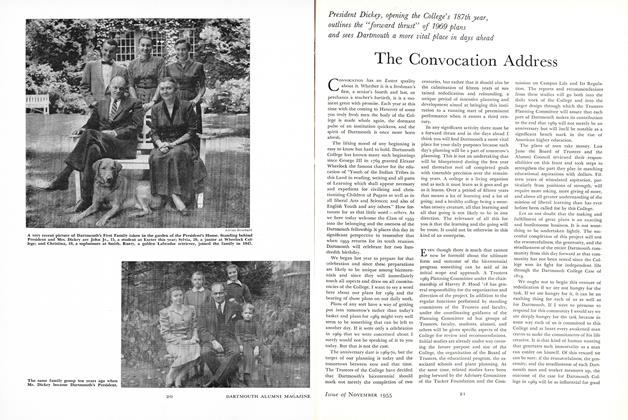

The beginning: this V-12 review was photographed in 1943

when the Navy trainees at Dartmouth numbered approximately 2,000 compared to only a few hundred "civilian" undergraduates.

Professor Radway, author of several books and articles on militaryaffairs, has been a member of the Government Department since 1950. He was one of seven faculty members who petitioned theTrustees, in 1972, to reopen discussions on ROTC.

*The extent to which state university students are required to take ROTCis a matter of state law and service custom. The Navy does not maintaincompulsory units. As recently as 1963-64, however, about half of allArmy and Air Force enrollees participated in required programs. TheLand Grant Act of 1862 required state universities to offer military instruction but did not provide support, standards, and supervision of thekind the federal government now makes available to ROTC units.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureONE HUNDRED MASTER DRAWINGS

October 1973 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Feature

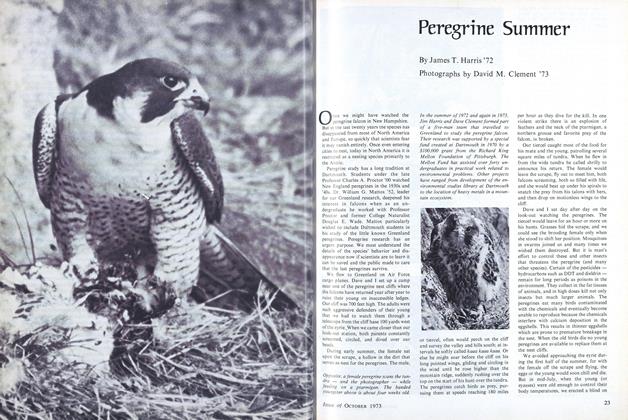

FeaturePeregrine Summer

October 1973 By James T. Harris '72 -

Feature

FeatureArcheological "Amateur"

October 1973 -

Feature

FeaturePort Professional

October 1973 By M.B.R. -

Article

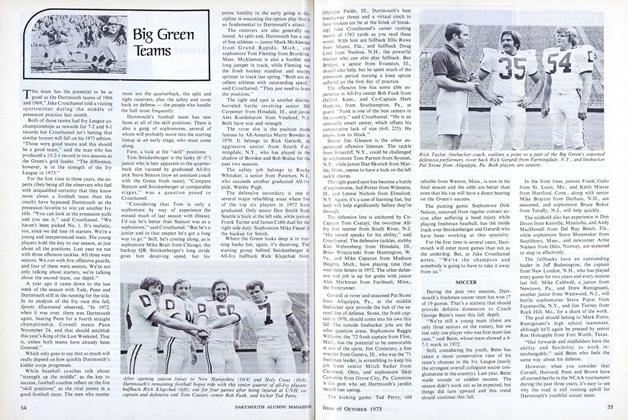

ArticleBig Green Teams

October 1973 By JACK DEGANGE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1973

October 1973 By STEPHEN H. QUIGLEY, JAMES T. BROWN

LAURENCE I. RADWAY

-

Feature

FeatureHow Much Government?

March 1954 By LAURENCE I. RADWAY -

Books

BooksFREEDOM OF SPEECH BY RADIO AND TELEVISION.

APRIL 1959 By LAURENCE I. RADWAY -

Books

BooksFOREIGN AID AND AMERICAN FOREIGN POLICY: A DOCUMENTARY ANALYSIS.

JANUARY 1967 By LAURENCE I. RADWAY -

Books

BooksMAN INCORPORATE, THE INDIVIDUAL AND HIS WORK IN AN ORGANIZED SOCIETY.

November 1968 By LAURENCE I. RADWAY -

Books

BooksNot in the Stars

January 1976 By LAURENCE I. RADWAY -

Books

BooksThe New Right

November 1979 By Laurence I. Radway

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Convocation Address

November 1955 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni Council Nominates Three for College Trustees

FEBRUARY 1971 -

Cover Story

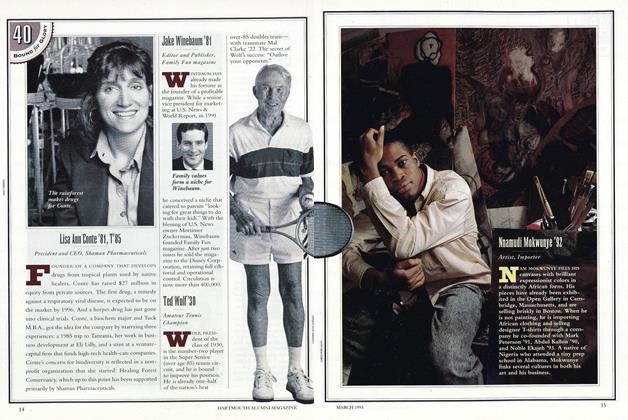

Cover StoryLisa Ann Conte '81, T'85

March 1993 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryPRESIDENTIAL SEAT CUSHION

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

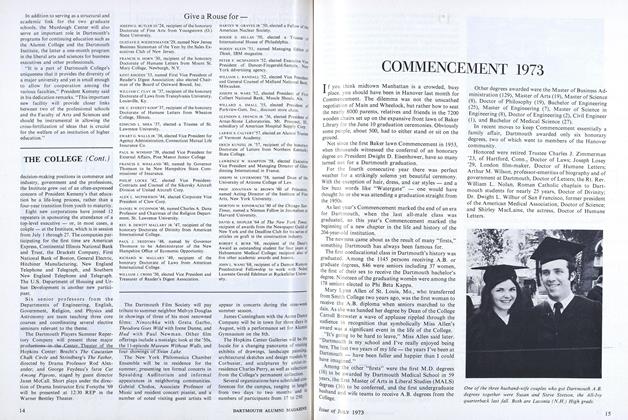

FeatureCOMMENCEMENT 1973

JULY 1973 By CHARLES J. KERSHNER -

Feature

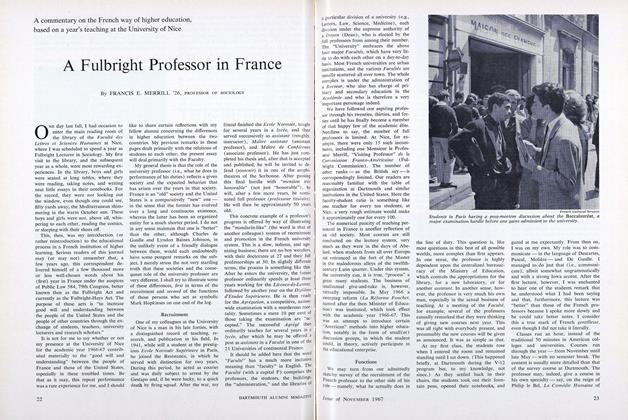

FeatureA Fulbright Professor in France

NOVEMBER 1967 By FRANCIS E. MERRILL '26