Remarks at the convocation dedicatingthe Eugene Shedden Farley Library atWilkes College, Wilkes-Barre, Pa.

I COUNT it a privilege to participate in this ceremony to dedicate the Eugene Shedden Farley Library. I offer my congratulations to those who developed the plans for this magnificent facility and my admiration for those who have made it a reality. I am moved to celebrate all that this new library stands for - books, ideas, the aspirations of the men and women who will study here, and, most of all, the orderly and rational process of learning which is symbolized by a house of books.

These are violent times, and violent ideas are astir across the land. Let us use this occasion to dedicate ourselves to the rational, reasonable processes by which peaceful men confront challenge and change.

I believe that we have reached a point of crisis in American life which requires such dedication, particularly from those of us engaged in the process of higher education, whether as students, teachers, administrators, or trustees. My text is a simple statement of wisdom by Will Durant, whose life has been devoted to the study of man's earthly history and whose eyes have traveled across the whole panorama of western civilization. He epitomized our present struggle in these few words and warned, "When liberty destroys order, the hunger for order will destroy liberty."

All of us are too painfully familiar with the evidence that order has been strained to breaking in recent years. We have seen dissent erupt into violence, and we have watched the assertion of raw authority as the only alternative to chaos. The forces of liberty and order have reached the point of open conflict, and the college campus has become the battleground for confrontation. The most cynical of campus radicals seek to destroy all that libraries stand for.

I want to speak briefly about the student revolt, and I do so as a battlescarred veteran who may qualify for several Oak Leaf Clusters. I have observed the approaching conflict for the past ten years from behind (fortunately never under) a dean's desk, where I have been picketed, sat-in on, and marched on. I have addressed a protest rally from the steps of the administration building, and I have scrubbed off paint from the pavement in front of my home. I think I understand the style of the would-be revolutionaries who have so successfully exploited the generous instincts of the academic community.

Surely it is no surprise that I am utterly intolerant of violence and the threat of violence. The style of hard-core campus radicals is tactics; their mood is cynical; and their goal is political power. But it may be a surprise that I sympathize very much with the causes which they proclaim. I bought a book recently about the New Left, and the cover carried the message that "campus radicals are marching against racism, puritanism, militarism, and bureaucracy." Well I'm marching against these things, too — as I dare say everyone in this hall is - but to a different drummer. Our steps take us to your new library, a symbol of rational processes, and I find its doors open, not blocked by barricades.

The radical movement threatens to polarize our campuses and our society. I believe that the present academic year, 1968-1969, will be a crucial test for American higher education. It is a time which calls for collaborative effort on the part of all of us pursuing the goals of higher education. If we are to preserve liberty, we must ourselves preserve order.

I am concerned that so many fail to understand that this violence, this style, can produce only one reaction. We can measure it already, by the recent Congressional legislation to deny federal financial assistance to students involved in campus disorders; by the Wallace vote; by the fact that 77% of Americans endorsed Mayor Daley's treatment of Chicago demonstrators. Last June a Dartmouth senior attacked the Vietnam war in his valedictory address, and his Phoenix, Arizona, draft board immediately reclassified him 1-A, despite the fact that he was a life-long practicing Quaker. The reason, they explained, was what he said at Dartmouth. Already there are signs that society's demand for order is at the expense of campus liberty.

I am alarmed that violent men can too often win the support of so many of our best students and faculty. And yet, unless "the system" can offer a response and an alternative, I see in the year ahead another cycle of disruptive action and hardening reaction. I would propose three things: First, let us unambiguously repudiate the disruptive tactics of campus radicalism. Second, let college faculty and staff respond with speed and sensitivity to the legitimate aspirations of their students. Third, let students develop a reasonable style for expressing their concern and implementing constructive change.

Let me digress a moment to describe the style of the practitioners of confrontation politics. They exploit issues for political not ideological reasons - power not principle. They are not reluctant to explain that their style aims to polarize attitudes, to create crisis, to disrupt orderly processes, so that they can claim victory either for concessions won or for the chaos they have created. The pattern has become nearly classic. First, identify an issue about which many students dents - faculty - have strong feelings. Develop and escalate the climate with the support of the campus newspaper. Exploit the eternal tension between students and faculty and The Administration by directly involving deans, trustees, and the president. Whether the issue is parietals and parking, or Dow and ROTC, the strategy is to establish a coalition and develop a focus. There must be a clearly defined, quite simple issue; there must be an enemy who represents unpopular authority; and finally an incident must be provoked to serve as catalyst. These explosive ingredients have shattered campus after campus. We must understand this style for what it is, and then we must repudiate it as absolutely incompatible with the rational processes of a civilized community.

Now let me share some observations with those of you who have bet your lives on the young people whom you serve as teachers, administrators, and trustees. It is not enough for us to deplore violence and disruption without offering a positive alternative. We must begin by recognizing that the best of our young people are raising good questions. They have identified the gaps in our society and have helped us to see ourselves as a nation that too often says one thing and does another. The best of our young people call out for individual participation in our institutions, our communities, and our society. We must be prepared in good faith to respond. I understand the student who recently carried a sign on our campus: "I am a human being. Do not fold, bend, spindle, or mutilate me"; and I've always sympathized with my friend who is in open revolt against direct dialing. When he wants 603-643-2536, he asks the operator for "six billion, thirty-six million, four hundred thirty-two thousand, five hundred thirtysix."

Let us recall that when our over-thirty generation was young, the social "system" faced two crises: a depression and a war. The system solved them both, in terms that were measurable and finite. The present college generation has no reason for the same confidence in the system, for it perceives no sign of victory in today's wars, whether in Vietnam or against poverty, injustice, ignorance, or urban blight. I know that we all pray that the President's decision to stop the bombing in North Vietnam represents a turning point - not only in the war, but also in national confidence in our system of government and the democratic process. I pray that this decision represents a significant moment of reconciliation for our people. We must do our best to respond in all areas, to get the system moving, pledging ourselves to work with Whatever tools are closest at hand. Most of all, perhaps, we must resist the visceral reaction to style which makes every issue a test of authority measured in terms of "giving in" to "demands." An orderly society is preserved by its capacity to respond reasonably. We must learn to separate our reaction to the style of dissent from our response to the significant issues that are presented.

Now let me turn to those among you who are students. I have watched my own campus grow in concern, conviction, and commitment over the past ten years, and I know that these qualities are a real part of Wilkes College. I find in your ideals a degree of moral awareness and social concern which makes me proud to be associated with you. While developing impressive competence to meet the demands of a complex society, you have demonstrated a sense of conscience which gives promise that mind and heart will work together in your lives. Nevertheless, I would make bold to offer some specific suggestions to each of you as you participate in the life of your college and as your college shares in the quest for solutions to the problems of our society. I begin with the example of your fine new library.

First, I urge you to use this library and stay loyal to all that it represents. Your education provides you with tools to analyze problems and fashion solutions. It has been my own experience that too many students who commit themselves to campus and public issues display a shocking ignorance of facts. They seem to be saying, "I know what I believe; don't confuse me with all these facts." Their response is too often intuitive and emotional, where it should be analytical and rational. Their actions too often are motivated by a kind of paranoid animosity which makes enemies of those in authority (be they parents, teachers, deans, or college presidents). They are not concerned with ideas that come from books, but rather slogans that come from signs.

Second, I would urge you to be discriminating in the issues with which you identify yourselves. Campus crusades which center on self-gratification do little credit to those who espouse them so passionately. Somehow, in view of all the needs of the world, college students seem terribly self-centered when they commit themselves to a sleep-in to protest parietals or a park-in to protest automobile regulations.

Third, to be truly effective in bringing about social progress, you must substitute conversation for confrontation. You do well to avoid the now-classic trappings of the political activist; beards, beads, and bells are an obstacle to genuine communication between the groups that must be able to reason together. The person in the New Left uniform is going to be written off by the very people he says he wants to reach and persuade. Part of the New Left uniform is rudeness, and I hope that we never forget the old-fashioned virtue of manners—a fundamental respect for the dignity and humanity of others. A wise psychiatrist once said, "Neurosis is no excuse for bad manners."

Fourth, your greatest contribution can be the exercise of the unique gift which youth brings to a society: impatience. It is essential that you continue to ask the hard questions and expect a reasonable response. At the same time, I urge you for your own sense of fulfillment and effectiveness to balance impatience with a realistic understanding of the possible.

These are four quite obvious and perhaps unnecesary suggestions. Permit me to add a filth, which shouldn't really count, I suppose. I urge you to keep your sense of humor. The capacity to laugh at ones self, to see the humorous side of any situation, is fundamental to man's capacty for rationality. If there is any characteristic which forces me to doubt the balance, objectivity and judgment of the radical politician, it is his utter lack of humor.

I have tried to define the urgency of the problems of liberty and order in higher educaion today, and I have urged a collaborative effort on the part of all of us to resolve them for ourselves. Edmund Burke writing two hundred years ago, described the stakes in a few short sentences: "Society cannot exist unless a controlling power upon will and appetite be placed somewhere, and the less of it there is within, the more there must be without. It is ordained in the constitution of things that men of intemperate minds cannot be free. Their passions forge their fetters.'

A pessimist would predict more passion and more fetters, but I confess myself an optimist who puts his faith in peaceful men. I sense that the academic community has already repudiated violence; that colleges are increasingly responsive to the needs and interests of their students; that there is emerging a new brand of student leadership, a new style, which is motivated by good sense and good will. This library reminds us of the stake we have in preserving our liberty as it serves the rational processes of an orderly society. May it always serve the highest aspirations of the faculty and students of Wilkes College.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature"Our trusty and well-beloved John Wentworth Esq., Governor"

December 1968 By Susan Liddicoat -

Feature

FeaturePolitical Year 1968: A Reprise

December 1968 By EDWARD W. GUDE '59, INSTRUCTOR IN GOVERNMENT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1934

December 1968 By STANLEY H. SILVERMAN, EDWARD S. BROWN JR. -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty

December 1968 By WILLIAM R. MEYER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

December 1968 By RICHARD K. MONTGOMERY, C. HALL COLTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1949

December 1968 By THOMAS J. SWARTZ JR., HERMAN E. MULLER JR.

Features

-

Feature

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1962 -

Cover Story

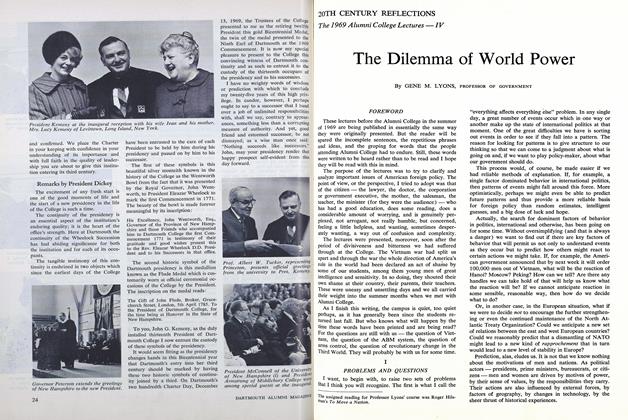

Cover StoryJean Baptiste

OCTOBER 1997 -

Feature

FeatureThe Dilemma of World Power

APRIL 1970 By GENE M. LYONS -

Feature

FeatureConundrum of the Gridiron

October 1978 By Jack DeGange -

Feature

FeatureRecommended Reading

Sept/Oct 2010 By LAUREN BOWMAN ’11 -

Feature

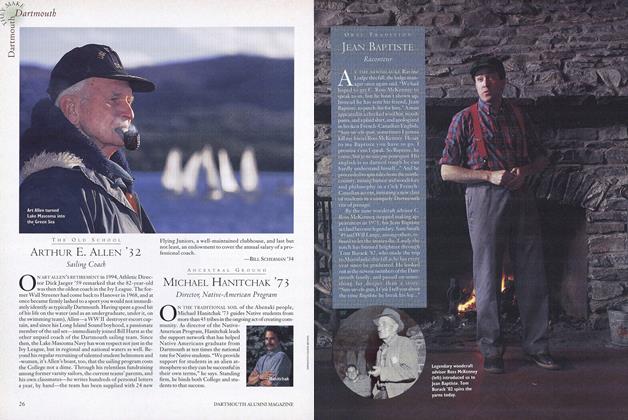

FeatureProps, Wingers, And Keepers Of The Old School

APRIL 1999 By Stuart Krohn