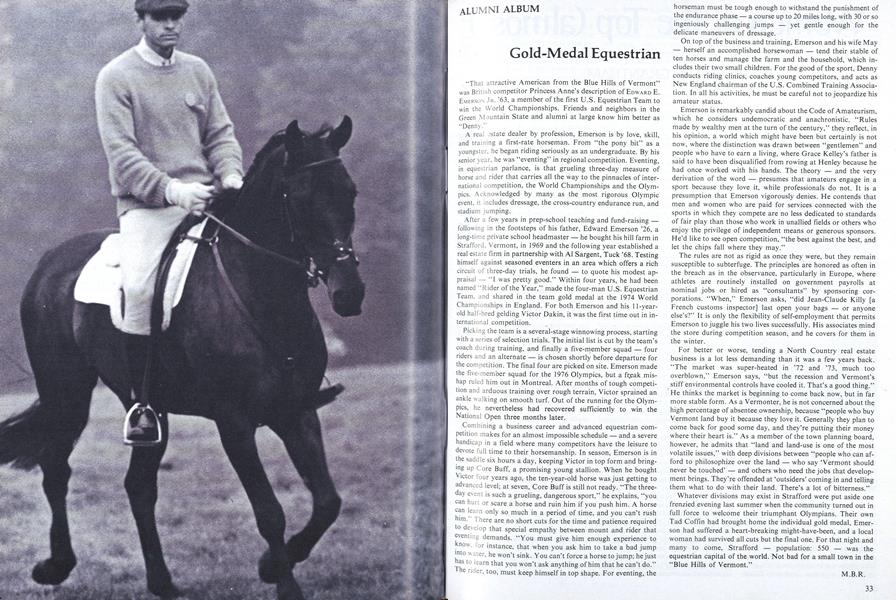

"That attractive American from the Blue Hills of Vermont" was British competitor Princess Anne's description of EDWARD E. EMERSON JR. '63, a member of the first U.S. Equestrian Team to win the World Championships. Friends and neighbors in the Green Mountain State and alumni at large know him better as "Denny."

A real -state dealer by profession, Emerson is by love, skill, and training a first-rate horseman. From "the pony bit" as a youngster, he began riding seriously as an undergraduate. By his senior year, he was "eventing" in regional competition. Eventing, in equestrian parlance, is that grueling three-day measure of horse and rider that carries all the way to the pinnacles of international competition, the World Championships and the Olympics. Acknowledged by many as the most rigorous Olympic event, it includes dressage, the cross-country endurance run, and stadium jumping.

After a few years in prep-school teaching and fund-raising - following in the footsteps of his father, Edward Emerson '26, a long-time private school headmaster - he bought his hill farm in Strafford, Vermont, in 1969 and the following year established a real estate firm in partnership with Al Sargent, Tuck '68. Testing himself against seasoned eventers in an area which offers a rich circuit of three-day trials, he found - to quote his modest appraisal - "I was pretty good." Within four years, he had been named "Rider of the Year," made the four-man U.S. Equestrian Team, and shared in the team gold medal at the 1974 World Championships in England. For both Emerson and his 11-year- old half-bred gelding Victor Dakin, it was the first time out in international competition.

Picking the team is a several-stage winnowing process, starting with a series of selection trials. The initial list is cut by the team's coach during training, and finally a five-member squad - four riders and an alternate - is chosen shortly before departure for the competition. The final four are picked on site. Emerson made the five-member squad for the 1976 Olympics, but a freak mishap ruled him out in Montreal. After months of tough competition and arduous training over rough terrain, Victor sprained an ankle walking on smooth turf. Out of the running for the Olympics, he nevertheless had recovered sufficiently to win the National Open three months later.

Combining a business career and advanced equestrian competition makes for an almost impossible schedule - and a severe handicap in a field where many competitors have the leisure to devote full time to their horsemanship. In season, Emerson is in the saddle six hours a day, keeping Victor in top form and bringing up Core Buff, a promising young stallion. When he bought Victor four years ago, the ten-year-old horse was just getting to advanced level; at seven, Core Buff is still not ready. "The three-day event is such a grueling, dangerous sport," he explains, "you can hurt or scare a horse and ruin him if you push him. A horse can learn only so much in a period of time, and you can't rush him There are no short cuts for the time and patience required to develop that special empathy between mount and rider that eventing demands. "You must give him enough experience to know, for instance, that when you ask him to take a bad jump into water, he won't sink. You can't force a horse to jump; he just has to learn that you won't ask anything of him that he can't do." The rider, too, must keep himself in top shape. For eventing, the horseman must be tough enough to withstand the punishment of the endurance phase - a course up to 20 miles long, with 30 or so ingeniously challenging jumps - yet gentle enough for the delicate maneuvers of dressage.

On top of the business and training, Emerson and his wife May - herself an accomplished horsewoman - tend their stable of ten horses and manage the farm and the household, which includes their two small children. For the good of the sport, Denny conducts riding clinics, coaches young competitors, and acts as New England chairman of the U.S. Combined Training Association. In all his activities, he must be careful not to jeopardize his amateur status.

Emerson is remarkably candid about the Code of Amateurism, which he considers undemocratic and anachronistic. "Rules made by wealthy men at the turn of the century," they reflect, in his opinion, a world which might have been but certainly is not now, where the distinction was drawn between "gentlemen" and people who have to earn a living, where Grace Kelley's father is said to have been disqualified from rowing at Henley because he had once worked with his hands. The theory - and the very derivation of the word - presumes that amateurs engage in a sport because they love it, while professionals do not. It is a presumption that Emerson vigorously denies. He contends that men and women who are paid for services connected with the sports in which they compete are no less dedicated to standards of fair play than those who work in unallied fields or others who enjoy the privilege of independent means or generous sponsors. He'd like to see open competition, "the best against the best, and let the chips fall where they may."

The rules are not as rigid as once they were, but they remain susceptible to subterfuge. The principles are honored as often in the breach as in the observance, particularly in Europe, where athletes are routinely installed on government payrolls at nominal jobs or hired as "consultants" by sponsoring corporations. "When," Emerson asks, "did Jean-Claude Killy [a French customs inspector] last open your bags - or anyone else's?" It is only the flexibility of self-employment that permits Emerson to juggle his two lives successfully. His associates mind the store during competition season, and he covers for them in the winter.

For better or worse, tending a North Country real estate business is a lot less demanding than it was a few years back. "The market was super-heated in '72 and '73, much too overblown," Emerson says, "but the recession and Vermont's stiff environmental controls have cooled it. That's a good thing." He thinks the market is beginning to come back now, but in far more stable form. As a Vermonter, he is not concerned about the high percentage of absentee ownership, because "people who buy Vermont land buy it because they love it. Generally they plan to come back for good some day, and they're putting their money where their heart is." As a member of the town planning board, however, he admits that "land and land-use is one of the most volatile issues," with deep divisions between "people who can afford to philosophize over the land - who say 'Vermont should never be touched' - and others who need the jobs that development brings. They're offended at 'outsiders' coming in and telling them what to do with their land. There's a lot of bitterness."

Whatever divisions may exist in Strafford were put aside one frenzied evening last summer when the community turned out in full force to welcome their triumphant Olympians. Their own Tad Coffin had brought home the individual gold medal, Emerson had suffered a heart-breaking might-have-been, and a local woman had survived all cuts but the final one. For that night and many to come, Strafford - population: 550 - was the equestrian capital of the world. Not bad for a small town in the "Blue Hills of Vermont."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWomen at the Top (almost)

May 1977 By SHELBY GRANTHAM -

Feature

FeatureOISER: Massaging the Media

May 1977 By PIERRE KIRCH -

Feature

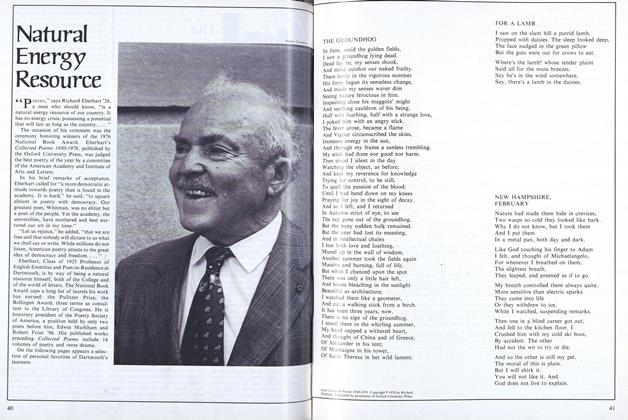

FeatureNatural Energy Resource

May 1977 -

Article

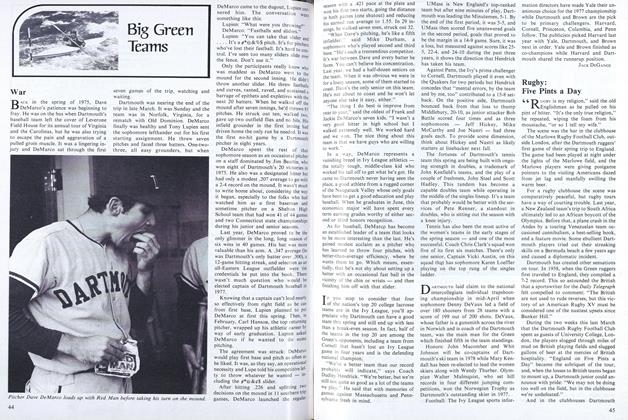

ArticleWar

May 1977 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticlePaddler, Climber, 4-term Planner

May 1977 By D.M.N. -

Books

BooksNotes on justice finally done and old tales long in the telling.

May 1977 By R.H.R. '38

M.B.R.

Features

-

Feature

FeatureClub Officers Form Association

November 1957 -

Feature

FeatureThe Ivy League schedule for 1972 ... and some showdown games

OCTOBER 1972 -

Feature

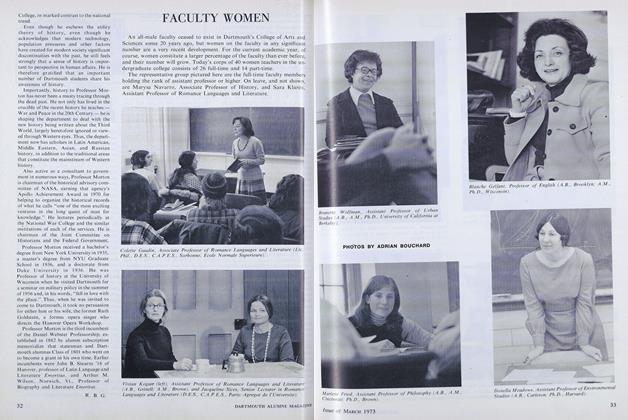

FeatureFACULTY WOMEN

MARCH 1973 -

Feature

FeatureThe Commencement Address

JULY 1971 By GUNNAR MYRDAL, Sc.D. '71 -

Feature

FeatureLife on Campus Is Slated for an Overhaul

June 1987 By Lee Michaelides -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO WIN CUSTOMERS WITH UNPRECEDENTED SERVICE

Jan/Feb 2009 By SCOTT MITCHELL '93