CURATOR OF GREEK AND ROMAN ART, THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART

THROUGH the munificence of Ray Winfield Smith '18, Dartmouth College has recently come into possession of an important Greek vase which is here published for the first time. The purpose of the gift, a unique revival of ancient customs, was explained in last month's ALUMNI MAGAZINE. This note is confined to the interpretation of the vase and a sketch of the Panathenaic competitions for which it was originally made.

The Panathenaic festival was celebrated in Athens on the birthday of the goddess Athena, the 28th of the Attic month Hekatombaion, the first month after the summer solstice. This would put the festival in the third week of July, according to our calendar. A distinction is made between the annual festival and the Great Panathenaia, which - like the Olympic Games - were celebrated every four years. The Great Panathenaia took place at the same interval, but two years after the Olympic Games. Our accounts of the festival, its origin and program, are incomplete, but one aspect of it, the procession at the Great Panathenaia, is magnificently illustrated in the frieze of the Parthenon, familiar to every visitor to Athens and the British Museum.

Like many other Greek festivals, the Panathenaia were celebrated with competitions of which some were organized by teams, such as a relay race with torches, a boat-race, and a dance in armor; others were individual in character and consisted of three categories: hippie, athletic, and musical. Here again our sources are fragmentary, but the custom of awarding olive oil in jars as prizes in some of the competitions is known not only from inscriptions, which record the winners, but also from a large and representative series of the jars themselves, which have been recovered in excavations. These jars, which go under the name of Panathenaic amphorae, are remarkably traditional in character. The series begins with a vase in the British Museum, dated by us in the second quarter of the sixth century B.C., and continues well into the Hellenistic period. The shape remains essentially the same: an ovoid body, a small neck and mouth, and a narrow base. In scale, certain differences are noted: there is a fullsized version which usually bears the inscription "One of the prizes from Athens," a smaller variety which is normally uninscribed, and, in the fourth century, a series of miniature vases which look like souvenir copies. Some of the full-sized, inscribed amphorae have been measured as to their capacity, which is remarkably uniform, about ten and a half gallons. This measure tallies very closely with that of the Attic "metretes," and it may be conjectured that the inscribed amphorae of the large size were meant to contain a standard amount of olive oil.

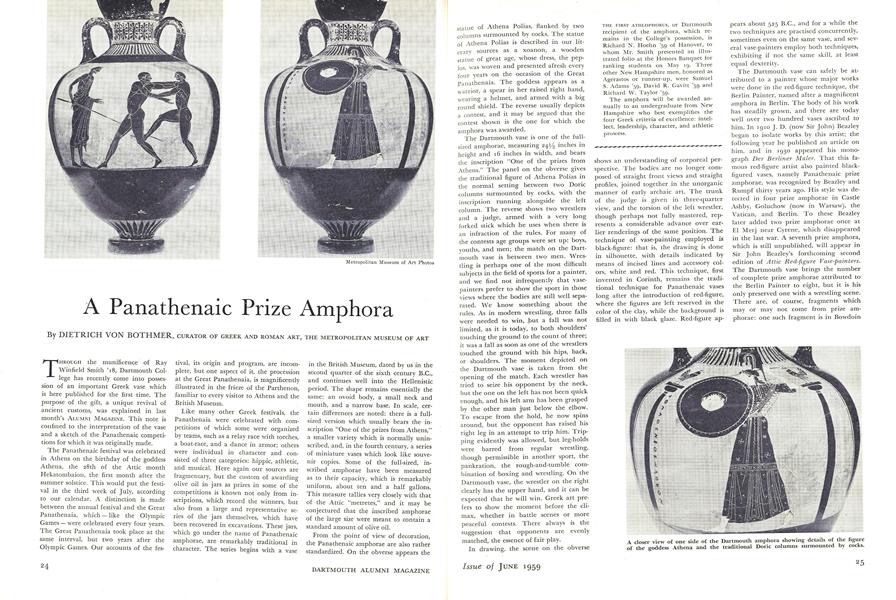

From the point of view of decoration, the Panathenaic amphorae are also rather standardized. On the obverse appears the statue of Athena Polias, flanked by two columns surmounted by cocks. The statue of Athena Polias is described in our literary sources as a xoanon, a wooden statue of great age, whose dress, the peplos, was woven and presented afresh every four years on the occasion of the Great Panathenaia. The goddess appears as a warrior, a spear in her raised right hand, wearing a helmet, and armed with a big round shield. The reverse usually depicts a contest, and it may be argued that the contest shown is the one for which the amphora was awarded.

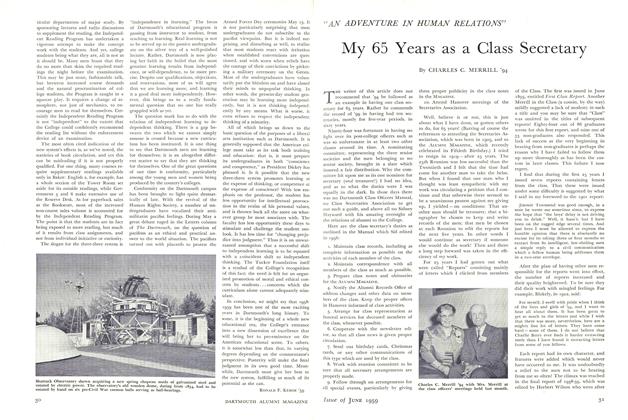

The Dartmouth vase is one of the fullsized amphorae, measuring 24½ inches in height and 16 inches in width, and bears the inscription "One of the prizes from Athens." The panel on the obverse gives the traditional figure of Athena Polias in the normal setting between two Doric columns surmounted by cocks, with the inscription running alongside the left column. The reverse shows two wrestlers and a judge, armed with a very long forked stick which he uses when there is an infraction of the rules. For many of the contests age groups were set up: boys, youths, and men; the match on the Dartmouth vase is between two men. Wrestling is perhaps one of the most difficult subjects in the field of sports for a painter, and we find not infrequently that vasepainters prefer to show the sport in those views where the bodies are still well separated. We know something about the rules. As in modern wrestling, three falls were needed to win, but a fall was not limited, as it is today, to both shoulders' touching the ground to the count of three; it was a fall as soon as one of the wrestlers touched the ground with his hips, back, or shoulders. The moment depicted on the Dartmouth vase is taken from the opening of the match. Each wrestler has tried to seize his opponent by the neck, but the one on the left has not been quick enough, and his left arm has been grasped by the other man just below the elbow. To escape from the hold, he now spins around, but the opponent has raised his right leg in an attempt to trip him. Tripping evidently was allowed, but leg-holds were barred from regular wrestling, though permissible in another sport, the pankration, the rough-and-tumble combination of boxing and wrestling. On the Dartmouth vase, the wrestler on the right clearly has the upper hand, and it can be expected that he will win. Greek art prefers to show the moment before the climax, whether in battle scenes or more peaceful contests. There always is the suggestion that opponents are evenly matched, the essence of fair play.

In drawing, the scene on the obverse shows an understanding of corporeal perspective. The bodies are no longer composed of straight front views and straight profiles, joined together in the unorganic manner of early archaic art. The trunk of the judge is given in three-quarter view, and the torsion of the left wrestler, though perhaps not fully mastered, represents a considerable advance over earlier renderings of the same position. The technique of vase-painting employed is black-figure: that is, the drawing is done in silhouette, with details indicated by means of incised lines and accessory colors, white and red. This technique, first invented in Corinth, remains the traditional technique for Panathenaic vases long after the introduction of red-figure, where the figures are left reserved in the color of the clay, while the background is filled in with black glaze. Red-figure appears about 525 B.C., and for a while the two techniques are practised concurrently, sometimes even on the same vase, and several vase-painters employ both techniques, exhibiting if not the same skill, at least equal dexterity.

The Dartmouth vase can safely be attributed to a painter whose major works were done in the red-figure technique, the Berlin Painter, named after a magnificent amphora in Berlin. The body of his work has steadily grown, and there are today well over two hundred vases ascribed to him. In 1910 J. D. (now Sir John) Beazley began to isolate works by this artist; the following year he published an article on him, and in 1930 appeared his monograph Der Berliner Maler. That this famous red-figure artist also painted black-figured vases, namely Panathenaic prize amphorae, was recognized by Beazley and Rumpf thirty years ago. His style was detected in four prize amphorae in Castle Ashby, Goluchow (now in Warsaw), the Vatican, and Berlin. To these Beazley later added two prize amphorae once at El Merj near Cyrene, which disappeared in the last war. A seventh prize amphora, which is still unpublished, will appear in Sir John Beazley's forthcoming second edition of Attic Red-figure Vase-painters. The Dartmouth vase brings the number of complete prize amphorae attributed to the Berlin Painter to eight, but it is his only preserved one with a wrestling scene. There are, of course, fragments which may or may not come from prize amphorae: one such fragment is in Bowdoin College, the only other black-figured work by the Berlin Painter in this country.

On the Panathenaic vases by the Berlin Painter the shield device of Athena is always a gorgoneion. A few years ago a red-figured cup was found in the Athenian agora which was signed by Gorgos as potter but was in all probability painted by the artist we have come to know by the modern name "Berlin Painter." There is, as often, the possibility that the potter was also the painter: in this case his name would be Gorgos, and the gorgoneion on the Panathenaic vases would then be a

canting device, appropriate not only to Athena, but referring also to the potter and painter. This shield device is continued on Panathenaic vases by the Achilles Painter, who is recognized as a pupil of the Berlin Painter and who may have started out working for the same potter, possibly Gorgos himself.

Uniformity of shield devices is also observed in the Panathenaic prize amphorae by two other red-figure painters, the Kleophrades Painter and the Eucharides Painter, the device of the former being a pegasos, that of the latter a snake. The Eucharides Painter is later than the Kleophrades Painter, and while the Berlin Painter starts out at about the same time as the Kleophrades Painter, his Panathenaic vases are later than even those by the Eucharides Painter, and should be dated about 470 B.C. Examination of profiles allows us to place Panathenaic prize amphorae in a chronological order, and there does not seem to be any overlap in the Panathenaic vases by these three painters. It therefore looks as if the contract for all prize amphorae to be awarded in each given year went to one potter. This contract may have been renewed for another Panathenaic year: the amphorae painted by the Kleophrades Painter are by no means contemporary, the two in the Metropolitan Museum being separated by at least one Panathenaic interval.

A closer view of one side of the Dartmouth amphora showing details of the figure of the goddess Athena and the traditional Doric columns surmounted by cocks.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureMy 65 Years as a Class Secretary

June 1959 By CHARLES C. MERRILL '94 -

Feature

FeatureLOG DRIVE

June 1959 By DOUGLAS M. PEASE JR. '58 -

Feature

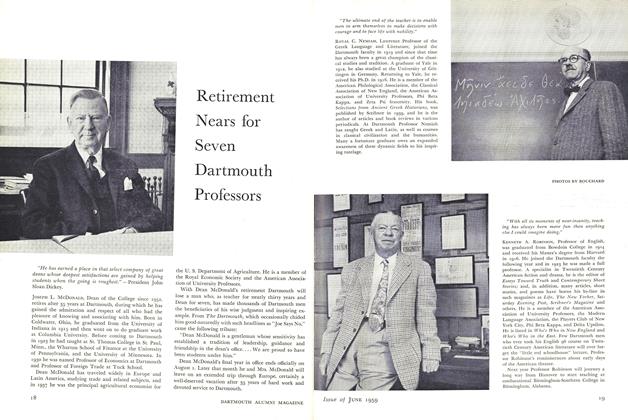

FeatureRetirement Nears for Seven Dartmouth Professors

June 1959 -

Article

ArticleThe Fraternity Discrimination Issue

June 1959 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

June 1959 By RONALD F. KEHOE '59 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1936

June 1959 By JOHN A. SAWYER, C. KIRK LIGGETT

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Big Day Draws Near

OCTOBER 1962 -

Cover Story

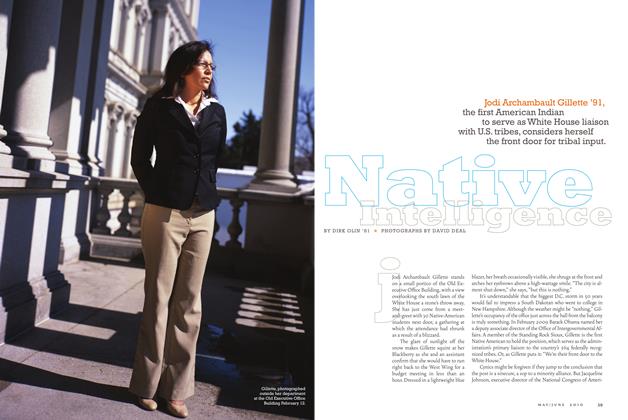

Cover StoryNative Intelligence

May/June 2010 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

Feature

FeatureAn Open Door Policy

July/August 2006 By Irene M. Wielawski -

Feature

FeatureHard times in the pressure-cooker

DECEMBER 1981 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureBeyond the Glory

Jan/Feb 2010 By SARAH TUETING ’98 -

Feature

FeatureWhat Price Glory?

OCTOBER • 1987 By Ted Leland